Table of Contents

ALSO BY LOU URENECK

Backcast: Fatherhood, Fly-fishing, and a River Journey

Through the Heart of Alaska

For Paul,

there from the beginning

The sun illuminates only the eye of the man, but shines into the eye and heart of the child.

Emerson

CHAPTER 1

THE URGE TO BUILD

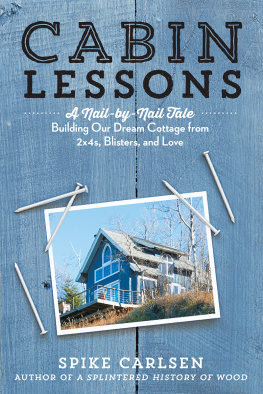

The idea had taken hold of me that I needed nothing so much as a cabin in the woodsfour rough walls, a metal roof that would ping under the spring rain and a porch that looked down a wooded hillside.

I had been city-bound for nearly a decade, dealing with the usual knockdowns and disappointments of middle age. I had lost a job, my mother had died and I was climbing back from a divorce that had left me nearly broke. I was a little wobbly but still standing, and I was looking for something that would put me back in lifes good graces. I wanted a project that would engage the better part of me, and the notion of building a cabina boys dream, reallyseemed a way to get a purchase on lifes next turn. I wont lie. I needed it badly.

So, on a day of warm September sunshine in 2008, after having bought a piece of land in western Maine the previous February, I stood in a corner of my brother Pauls suburban backyard in Portland and examined a stack of lumber I had dropped there more than a decade earlier. I had to stomp down the weeds with my brown leather brogues to get to it. I hadnt yet bought a pair of work boots. I was dressed for the classroom, where I now earned my living, disguised as a college professor: khaki trousers, buttondown cotton shirt and semiround tortoiseshell glasses. I confronted the wood; or maybe, as a symbolic artifact of an earlier life, it confronted me. It was a temporary standoff with the past. Piled chest high, the wood made an incongruous sight among the neighborhoods turquoise swimming pools, oversized gas grills and slumping badminton nets. To a passerby, it must have looked like a heap of old railroad ties dumped by the side of the road. I brushed the rough surface of the wood with my hand and pressed a thumbnail into its pulpy flesh. It was spongy: not a good sign. A few of the boards showed sawdust and smooth channels that were the work of carpenter ants. There were many more piecesheavy posts, big square beams and long silvery rafters with birds-mouth mortisesthat had come through the years of sun and snow mostly sound. I couldnt help feeling some affinity with the wood: weathered but mostly intact. This was what I had hoped for on the drive up from Boston, where I lived and worked. I had counted on salvaging enough lumber from the pile to form the frame of the cabin that already had taken shape in my mind.

Paul stood with me in his backyard. He was less sure about the wood.

I dont know, he said. A lot of its wet, maybe rotten.

Paul is an experienced and methodical builder. He typically works with architects, engineers, cranes and shipments of steel. He is the construction and project manager for a commercial real estate company in Portlandits vice president, in fact. He is a nonconformist in other parts of his lifea big man with a thick mustache, he drives a Harley-Davidson motorcycle wearing a sleeveless undershirt, open leather vest and a head kerchief tied tightly above his ears for a helmetbut he is cautious in matters of construction, the equivalent of the prudent and spectacled accountant. He applies conservative principles to the building of things, and he was exercising his professional caution on my woodpile. He might as well have been a banker sniffing weak collateral. I, on the other hand, was determined to work up the cabin from the old lumber, which would seriously reduce the projects cost and give me a rustic shelter that was an appreciation of the beauty of wood, and I wanted to get started right away. I was feeling the burden of his skepticism.

The roof is going to have to carry a big snow load in those hills, Paul said.

I could feel him inching closer to saying what he was actually thinking, which was that I should forget the woodpile and have a fresh bundle of two-by-four studs delivered from the lumberyard. That after all was the sensible thing to do: new lumber, new windows, prehung doors and prefabricated roof trusses. We could hire some help, engage subcontractors for the plumbing and electricity and have the cabin up in a few weekends. I would summarize his attitude as Lets make this easy and get to the part where we sit inside and enjoy the place.

Instead, I wanted to construct the cabin with these big woebegone slabs of wood in the old timber-frame method of building a barn, which meant employing, as much as possible, old-fashioned wood joinery rather than nails. It would hold together in much the same way as a chest of drawers assembled in a furniture shop. I wanted a place with some craft and heft and traditiona place that could make a natural and authentic claim to a piece of rugged Maine hillside. I didnt want a vacation home; I wanted a cabin. The rough-sawn and weathered beams, as I planned it, would be exposed inside the cabin just as they would be in a barn or backwoods Maine camp, and it would be sturdy and raised up from local materials, and it would be all the better for requiring the expenditure of time and skill with a mallet, wood chisel and framing square. And I wanted for us to do it all ourselves.

Paul listened to all of this without passing judgment or rolling his eyes. He was keeping an open mind, but I knew that I already had raised his suspicions when I showed him a bunch of dilapidated wood-frame windows I had scrounged over the summer for the price of hauling them away. They also were stored in his backyard.

Paul slid a rafter out of the pile that had the surface texture of Roquefort cheese. It was a good sixteen feet long. Its edges were gnawed and ragged. It crumbled in his hands.

Im not sure I want to be standing under this one when the snow on the roof gets to be four feet deep.

I had to agree with him about that particular rafter. It was awfully ratty and might snap under a load of wet snow.

Youre right, I said, wanting to keep him engaged in the project.

In this experiment in mental health, building the cabin with Paul was one of the reasons I wanted to build it at all. When you get around to reassembling your life, as I was doing, its good to have someone at your side who remembers how the parts once fit together.

Lets spread the wood out on the grass and put the bad pieces in a pile, I said. Well see what we have left.

Paul was agreeable, which is his natural disposition. His agreeableness is broken only now and again by a surfeit of suburban life. Then he gets gruff, bossy and next to impossible. He had inherited our mothers need for a little danger to keep life interesting, and when he doesnt get it, he turns surly. At present, he was living in a five-bedroom garrison with his wife, Laura, and their blended family of eight children, six of whom were at home, one at college, and another, Pauls oldest son, on a tour of duty in Iraq. Even in the best of times, when he accommodated himself to the routines of mowing the lawn, painting window trim or putting out citronella candles for a backyard barbecue for his and the neighbors kids, Pauls silent argument with the suburbs had a way of showing through. He was the only person in the neighborhood with a disassembled body of a stock car on blocks in the driveway.