Still No Word from You

ALSO BY PETER ORNER

Maggie Brown & Others

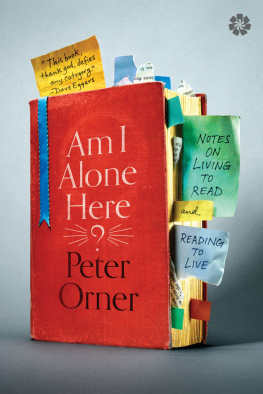

Am I Alone Here?: Notes on Living to Read and Reading to Live

Last Car Over the Sagamore Bridge

Love and Shame and Love

The Second Coming of Mavala Shikongo

Esther Stories

As Editor

Lavil: Life, Love and Death in Port-au-Prince

Hope Deferred: Narratives of Zimbabwean Lives

Underground America

For Katie, Phoebe, and Roscoe

and

Rhoda and Dan Pierce

And the sun that had risen in the morning would fall to its knees in the evening...

V IEVEE F RANCIS , Loving Me

Youre a fool. Go on, keep pedaling, its getting late.

P RIMO L EVI , The Periodic Table

Contents

A house remembers.

Edna OBrien

O N THE BLACK-AND-WHITE TV IN THE KITCHEN, MY mother and I watched Richard Nixons helicopter slowly rise. My mother stood at the sink doing dishes. At one point she stopped scrubbing but left her hands in the dishwater. The kitchen of the house on Hazel Avenue. The house no longer exists. It is less about her expression than that her hands remained in the water but were no longer scrubbing the dishes. Something to do with the stillness, her hands suddenly motionless in the soapy water. Maybe at that moment she wasnt thinking about Nixon at all. Which direction was she looking? Not at the TV. She was staring out at the backyard. The house on Hazel had a back patio with a low brick wall around it. I used to jump off the wall into the grass. The grass in the backyard of the house on Hazel was a deep, luscious green. If you yanked up a strand and pulled, it made a squeaky sound. Id eat that grass by the mouthful. I dont know which month of 1974 Nixon called it quits. I could check. Its exhausting being able to check anything and everything. Lets say it was spring, late spring, when Nixon resigned, and let it be wrong if its wrong, and that the grass in the backyard was a deep May green, especially where the shadow of our tall sycamore tree stretched across the lawn. My mother is looking out the window. She wouldnt leave Hazel Avenue, with my brother and me in tow, for almost another decade. But I know I read something in her eyes. As if shed already taken off. My mother, the sound of her splashing, scrubbing, and then, stillness.

T HERE S A MOMENT IN J AMES S ALTER S D USK WHEN A woman named Mrs. Chandler looks out a store window and sees the past. Its a simple line. It seemed as if it was years ago. Its a glimpse into the past that makes up any given present, that lurks, always, in the shadow of right now. Mrs. Chandler is only a woman in a small store, looking out the window at the cars going by on the road. Shes holding an onion. Its begun to rain. I remember where I was when I first read this scene. I was in the library at San Francisco State, between classes. 2004? 2005? Those years teaching kept me sane. Usually it was the other way around and the sound of my own voice made me cringe. At that time, going on and on, preaching the gospel of fiction kept me tethered, at least slightly, to the existence of other people. Otherwise, Id have completely retreated, where Im not exactly sure.

I was already late for my own class. I hadnt finished the story so I walked out with the book. The buzzer sounded. I kept moving. Nobody chased me. I still have it, a stolen orange hardcover, soiled from the grease of my hands.

Mrs. Chandler refuses to drive to the big store out by the highway. She always shops at the little market in town. Though she doesnt buy much anymore. Vera Pini, as always, is perched by the register. Vera tells Mrs. Chandler that shes got some good Brie today. Mrs. Chandler asks, Is it really good? Yes, Vera says, its very good.

On the plate glass the first drops of rain appear.

Look at that, Vera says, its started.

And thats when Mrs. Chandler, elegantly dressed Mrs. Chandler, looks out the window into years ago. Theres more to the story. Usually there is. But Im drawn lately to the moments before a story becomes a story. Like opening stage directions. Take The Cherry Orchard. It begins: A room which is still known as the nursery. One of the doors leads to ANYAs room. Half-light, shortly before sunrise. It is May already... The audience still shifting in their seats, tucking away their programs, never hears these lines. They are never spoken out loud. Its a beginning whispered only to a reader.

A woman stands in a store holding an onion. She looks out the window and sees a life thats gone. In the life, her husband and son used to meet her at the train station. I cant remember if she can see the station from where shes standing or not. Im not sure it matters. All thats in the distance. The narrator tells us, with annoying omniscience, that no one will ever desire Mrs. Chandler again, love her like that again, butagainthats the story becoming the story, a sad, sadly predictable story, and what I want right now are only these opening notes, the cheese thats very good, the first few drops of rain on the plate glass. Look at that. Its started.

D URING THE S ECOND W ORLD W AR MY MOTHER S FATHER was in the civil defense. This was in Fall River, Massachusetts. He carried a gun not much bigger than a cap gun. His responsibility was to make sure his fellow Fall Riverites had their windows properly blacked out. He would walk the streets of his own neighborhoodfrom Robeson Street to Dudley Street to Highland Avenueand hunt for light. They wouldnt send him overseas. He was 4-F, back trouble, feet as flat as paper plates. My mother told me hed painted an old leather football helmet silver and would practice a stern, authoritative face in the bathroom mirror. And if, on his nightly rounds, he spotted a crack of light beyond the blackout curtains, hed march up to the door, knock on it with four authoritative knuckles, and inform the violators in no uncertain terms that they were aiding and abetting the Luftwaffe by providing an opportunity, a target, a beacon. Am I being understood?

Grandpa Freddy was a mild-mannered guy, but give a man a gun, no matter how miniature, and something to enforce and hell lug the weight of the world across quiet lawns.

Though hed never gone to collegemy Fall River grandparents were seventeen when they eloped and Freddy went right to workhe considered himself a bit of a pointy head. On my shelf, I have his dog-eared Shakespeares Collected Works, print so small he must have needed a microscope to read it. Still on many of the pages there are notations in the margin, notes to himself. His faded handwriting now unreadable.

My grandfather makes his rounds. I think of him, walking his streets murmuring happily, a Jewish Othello with a bad back: Put out the light, and then put out the light.

He really did enjoy those urgent, whispered porch conversations. Not because he so enjoyed berating people or speechifying but because, emerging out of the night to rap on the door of a silent house, he expected the door not only to be answered but for the answerer to listen to him, Fred Kaplan, tell them what was what. Dont you see? Thats what theyre after, our light. Weve got to hoard the light, not forever, just now. Him in that goofball silver helmet. A little gun in his pocket. I have the thing here in a drawer. Freddys paunch, his worn-out loafers. He worked in his fathers furniture store. One day the store would be all his. Soon after that, in the 60s, the state of Massachusetts rammed a highway, I-195, through the downtown, like a stake through the heart of Fall River. Entire blocks fell, City Hall, the Hotel Mellen, Kaplans Furniture. They said it would bring the city business. My grandfather said, A highway will bring business? Theyll wave at us on their way to Providence. All that useless destruction would eventually kill him. But during the war he was third or fourth man on the stores totem pole. He was thirty-six years old. He punched the clock and still called his father sir.