F I P S

F I P S

Legendary U-Boat Commander

19151918

by

Werner Frbringer

Translated from the German by

Geoffrey Brooks

Originally published as Alarm! Tauchen!! U-Boot in Kampf

und Sturm by Ullstein, Berlin, in 1933.

First published in Great Britain 1999 by

Leo Cooper

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street,

Barnsley,

South Yorkshire,

S70 2AS

Copyright 1999 by Geoffrey Brooks

ISBN 0 85052 694 9

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

Typeset in 11/13pt Sabon by

Phoenix Typesetting, Ilkley, West Yorkshire.

Printed in England by Redwood Books Ltd.

Trowbridge, Wilts.

DEDICATION

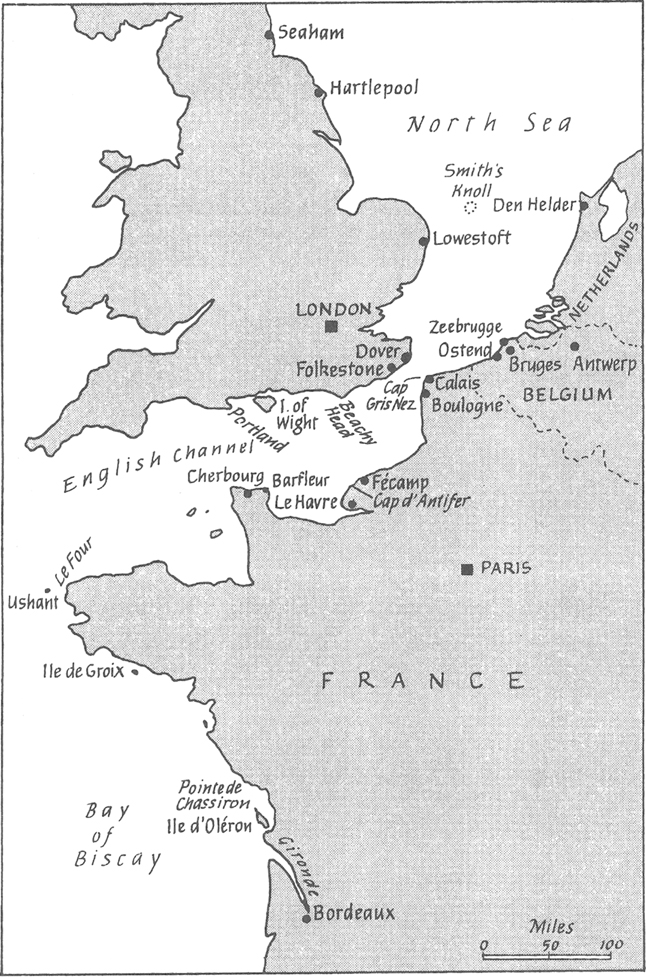

I dedicate this book to two innocent victims of the Great War: to the dearly loved Frbringer brother who as a private soldier in the German Army fell at Verdun on 31 May 1916; and to Mrs Mary Slaughter of Hebburn, a young lady visitor to the town of Seaham, who while taking a country walk in the company of a female relative on the evening of 12 July 1916 was hit by a shell fired by the German submarine UB-39 and succumbed to her terrible injuries at Sunderland Hospital the following morning, the only casualty of the incident.

CONTENTS

Werner Frbringer (b. Braunschweig 2 October 1888, d. 8 February 1982) was a career naval officer selected for the new U-boat Arm of the Imperial Navy. In the first six months of the Great War he served as first watchkeeping officer aboard U-20 for two voyages under Otto Schwieger, immediately prior to the mission when the latter torpedoed the Cunarder Lusitania in May 1915.

Frbringer was given his first command in April 1915 and from then until July 1918 operated out of the Bruges U-Boat base. No other submarine force in history has persevered with the 83% loss rate found acceptable by the Flanders U-Flotilla. Few officers survived to tell of their experiences and Frbringers memoir is probably unique.

In the desperate attempt to blockade Britain into surrender this small coastal submarine force wreaked havoc along the French and English coasts from Brest and Lands End to the Firth of Forth, minelaying and sinking by gun and torpedo all sizes of Allied vessel from troop transports to herring drifters.

It was a dangerous business and Frbringer provides a frank account of the awesome dangers that awaited the U-boat commander as soon as his boat emerged beyond the mole at Zeebrugge: great minefields, searchlight barriers, mined net barriers, Q-ships in all disguises and armed lighthouses.

He was without doubt not only a very brave man but also a humane and chivalrous officer.

I am indebted for their invaluable assistance to Hans-Gnther Frbringer, his son, also to my old friends Wolfgang Hirschfeld of Pln in Holstein, former Oberfunkmeister in Doenitz U-boat Arm, and to Philip Oastler of Southend-on-Sea, formerly of the British Merchant Navy, all of whom helped me with research and encouragement.

Geoffrey Brooks

Spain, 1999.

I entered the Imperial German Navy as an officer cadet on 1 April 1907 at the age of eighteen. After receiving my commission I was drafted aboard the newly completed large cruiser Scharnhorst, flagship of the Far East Cruiser Squadron, and sailed aboard her for the German colony of Tsingtau in 1909.

I had my baptism of fire in 1912. As senior Leutnant of the flagship I was seconded to Oberleutnant Metzenthin of our sister ship Gneisenau and ordered to proceed aboard the German steamer Titania with a detachment of fifty men to the defence of the German settlers in the trading town of Hankau 1000 kilometres upstream. The 1912 Chinese Revolution had broken out. Directly behind the German settlement at Hankau there had been bloody fighting between the Imperial forces and the rebels, and for this reason our presence was urgently required for the protection of German lives, property and the flag. We were enthusiastic, but understandably apprehensive at the prospect of knowing war at first hand.

On the afternoon of the fourth day of the voyage, as the Titania passed Kiu-Kiang, then known worldwide for its porcelain vases, one of the towns forts hoisted a string of flags. The international semaphore books were consulted, but, as no sense could be made of the signal, it was decided to ignore it. When we had the town a mile astern five of the forts guns opened fire. There were some muzzle flashes and a thunderous crack. A few seconds later a salvo of shells howled over. I ducked instinctively below the bridge railings. It was my baptism of fire.

The Chinese were obviously serious. Our ship dropped anchor and the wireless operator attempted to contact the gunboat Luchs and other German warships lying upstream, but neither they nor the cruiser squadron seemed disposed to reply. Oberleutnant Metzenthin went ashore to lodge a protest with the British consul, who represented German diplomatic interests for the district, but the revolutionary fort commander was adamant and refused to allow Titania to proceed on the grounds that she was carrying ammunition for the Chinese Imperial forces. The following evening Luchs wirelessed instructions to threaten the fort with bombardment by German warships and at dawn the Chinese commander relented.

Our arrival in Hankau was cheered vociferously by the German colony. To our disappointment we learnt that the Imperial forces had withdrawn, thus depriving us of a first taste of battle. The fields behind the town were piled high with corpses. German sentries reported frequent attacks in the darkness by large wild dogs which evidently had found an appetite for human flesh. Mopping-up operations were therefore limited to destroying as many of these animals as possible.

We identified closely with the German colony. A splendid spirit characterized the trading community in Hankau. They worked grimly from dawn till dusk and cherished great hopes for the future. In a way they were over-dedicated to being entrepreneurs and neglected to enjoy life. Almost to the last man they had the single objective of making as much money as possible before ultimately returning to Germany. The British had a healthier attitude. They would shut up shop early and keep fit and well with sport. Many of them had been in China for generations and were quite happy to settle there. Naturally they took a dim view of business being conducted at a brisker tempo than their own!

After six months at Hankau a relief party arrived and we returned to our beautiful, proud model colony of Tsingtau. The cruiser squadron embarked upon its 1912 summer voyage, calling at Japanese ports, the island of Sakhalin and anchoring in a number of bays on the coast of Eastern Siberia.

In August 1912 Scharnhorst had just anchored at Nagasaki. While supervising work on the focsle I noticed a naval pinnace come alongside to deliver the latest telegrams from Berlin. Shortly afterwards the commander called down to me from the bridge, Congratulations, Frbringer, youve been selected for U-boats! I had become the first officer to be selected for transfer into submarines from the cruiser squadron. Everybody seemed very excited about it in the wardroom and I was roundly congratulated. Privately I was unsure whether it was to be considered a distinction, but evidently my colleagues envied me.

I entrained at Vladivostok for Germany via Moscow and travelled through the bleak snowscape of a Siberian winter. Many races of mankind thronged the railway platforms. It was December 1912; war had broken out in the Balkans. At nearly every large station between Harbin and Moscow we passed troop transport trains heading west!

Next page