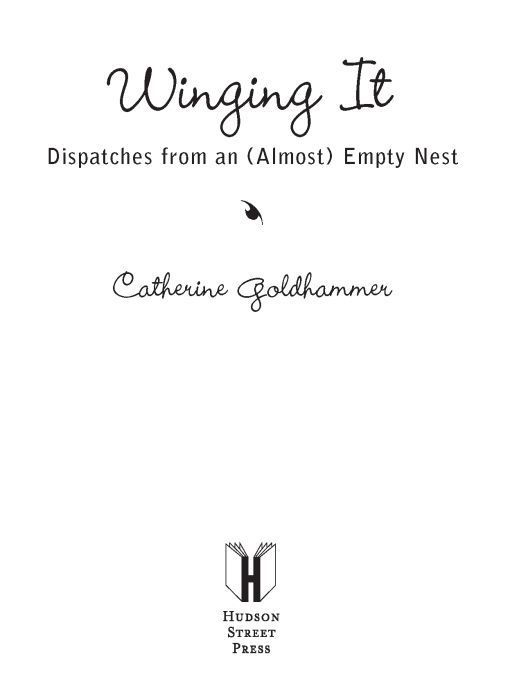

Table of Contents

For Henry

Introduction

When my daughter was twelve, we moved from the affluent suburb of her childhood to a tiny fixer-upper in a run-down seaside town in New England. I was newly divorced, and she was newly a teenager. We got chickens and we moved (in that order) and we renovated the new little house. I wrote a book, and my daughter grew from an eccentric gangly girl into a deep and mysterious young woman. I wondered, at some point in those days, when life changes were coming in waves, one quickly following another in massive seismic shiftsthe year of the divorce and the year of the move and the year of the bookwhat the next year would be. I should have seen it coming, but I did not.

Some kids are moving from the moment of birth. At the park toddlers blithely walk down slides or off the edges of wooden forts, and then climb back up to do it all again. Not mine. Harper wasnt a climber or a jumper or a runner. She watched, and talked, and drew. She drew three hundred pictures of ballerinas in the course of a weeks vacation when she was three. I then stopped buying pads of paper and instead bought rolls of shelf paper, which she covered, edge to edge, with elaborate universes of tiny stick figure girls. I built her complicated forts made out of couch cushions, bamboo poles, and long pieces of sea green silk. She never played in them. It drove me crazy. Years later I mentioned it.

Oh, she said, I thought you knew. I didnt want to play in them. I wanted to see how you built them.

I quickly learned that the primary joy and challenge of parenthood was to trust the spirit I had given birth to, and to know when to rein in and when to let go. Harper was simultaneously a homebody and a mental rover. She didnt sleep through the night until she was ten, complaining of the mist that pervaded her room in the middle of the night. (I believed in the mist, but had never seen it.) She didnt like to be away from home, and three-day elementary school trips required me to write two notes a day, seal them, and secret them in her duffle. She stopped reading them long before I stopped writing them.

Of course, the trips away became longer and I got more and more used to them, and so did she, until time away was just another part of life. She was always ready for the next step before I was and when she left for a college program in philosophy the summer she was fifteen, she, of course, did fine.

And so did I, mostly. Just one lost weekend and a few weekdays given to wandering around clueless. But then I got into the swing of things. I got up at the same time every day and fed Sam, the red hound, Monkey, the ghost gray cat, and the chickens. I had breakfast by the window. I did worthwhile things: made phone calls, moved my office from the tiny (and muddy) mudroom to my daughters old bedroom on the first floor (she had fled to the attic), and painted its bookcases a glossy black. I had a certain kind of energy that comes with time and the ability to concentrate. I got a lot done. I felt virtuous and productive. I made a Web site. I mailed the publication announcements for my first book. I had that reaching-out sort of feeling. The anything could happen now feeling. I was vital. I was on the upswing.

But every time my cell phone buzzed with a text message from Harper, I leaped. I became somewhat adept at texting back. Though the verb offended my sensibilities, the form of communication beat the sealed notes. Even so, it took me a half hour to send a reasonably amusing message. I went to the phone store and pondered the BlackBerry and the Treo. Perhaps I needed one of those, I reasoned. After all, they had a full keyboard and Internet connectivity, and the BlackBerry in particular struck me as a writerly, busy thing to have. This was not a new preoccupation. I fairly often tried to talk myself into getting a BlackBerry. As if having one would spice up my life. How, I did not know.

Then, in the back-and-forth of text messages and separate days, I began to understand what the next seismic shift was going to be. You have your children and you cant possibly imagine that one day they will walk off toward their own horizon. You really cant. You know it, but you dont. And then it happens and you have to let them go. It wasnt that I didnt know this. Not to get all Kahlil Gibran about it, but our children really are the arrows we send out into the future, and I knew that my daughter was walking toward that moment with intent, and that she was way ahead of me in readiness. According to my friends whod been there before me, knowing it didnt necessarily help.

We pour everything into them, an uncommonly gentle friend said with uncharacteristically bitter humor. And then they leave us, the little bastards.

And so, after years and yearsof scraping oatmeal off the floor with a spatula, retrieving plastic octopi from the mouths of toddlers, navigating the shoals of kindergarten and friendships and boyfriends, learners permits, drivers licenses, the specters of sex, drugs, and alcohol, the mind-opening bands with their strange names and poetic lyrics, the brain-sucking nightmare of MySpace and Facebook, the iPod with its thousands of songs, the singing lessons, the art classes, the heart-stopping riding lessons with their massive horses and five-foot jumps, the ambitions, the passions, the existential angst, the opportunity to revisit the Glass family, Rilke, and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenanceyou finally see it on the horizon. There you are. You. About to be returned to yourself.

Part One

These Windswept and Rocky Shores

Washed Up

Harper came back from the philosophy program with an Italian boyfriend and the announcement that she wasnt going back to high school. The Italian boyfriend, a dark-haired, model-handsome, gangly, joyous boy, full of faith and old-fashioned chivalry, was a surprise. The declaration was not. Harper hated high school. She had chafed against the confines of formal education and had longed for something more, the mental equivalent of death-defying. It hadnt come as a surprise when, instead of attending a cushy art camp in a bucolic setting, she went instead to the academically rigorous philosophy camp at a Catholic college with dorm rooms full of battered wooden castoffs and screens that only marginally fit the windows.

I want a true educational experience, shed said. And so, although she was not a Catholic, or religious at all for that matter, offshed gone, along with three suitcases full of stylish clothes and seven pairs of shoes. She called only a few times, and sent me text messages sporadically. Her language was different. When she used the words pure and religious crisis in the same text message, I, fearing she was under pressure from the Catholic majority, freaked out. Mom, she wrote, I brought my intelligence here, too.

They read hundreds of pages a night. They read Plato and Aristotle and studied the significance of the death of Socrates. They wrote papers on the meaning of melancholy and the place of the poet in society and the meaning of courage. And then she came back knowing something about the depth and breadth of her future. I knew within minutes of seeing her something I had known before but not really believed. She was going to grow up and do her job. She was going to leave me. She would set out on the journey of her life, and I would watch her go.