A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand

First published 2010. Reprinted 2010.

This book is copyright. Except for the purposes of fair reviewing no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

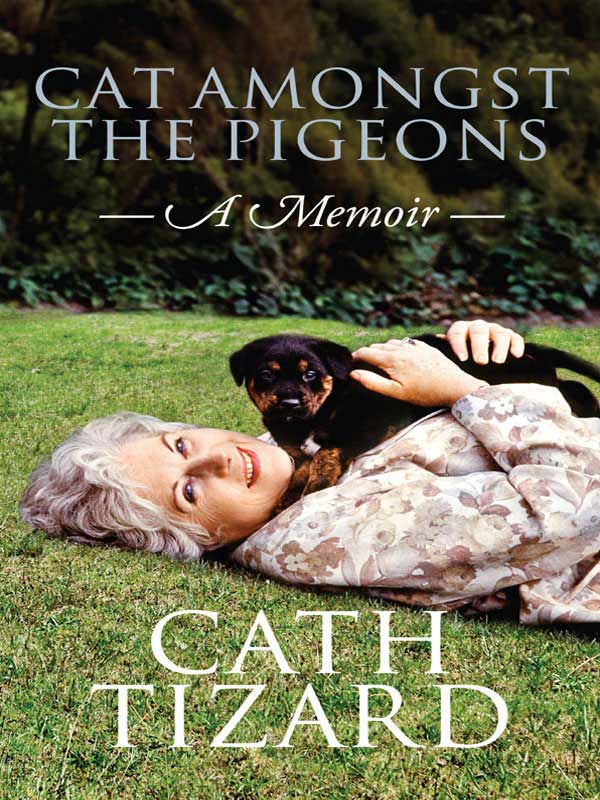

This should really be called something like My Lucky Life, because I certainly have had lots of luck in my life. When I say this, people often reply that I shouldnt put myself downwhich Im not. Loads of people with greater talents than any I can lay claim to have never had the opportunities that have opened up for me.

When I was young I was often patronisedmostly in a kindly wayfor being an only child, and I was certainly envious of my friends who had brothers and sisters. Oh, a lonely only! You must be spoilt was not an uncommon sentiment and it made me feel in some way inferior. In my more mature years, I came to realise that there are some advantages, in a not very well-to-do family, in being the sole beneficiary of family resources and aspirations. Yes, there are downsides but I still look back now with gratitude for that bit of good luck. The other fundamental piece of good luck was in having parents with social and educational ideals and principles that shaped their thinking and their livesand, eventually, mine.

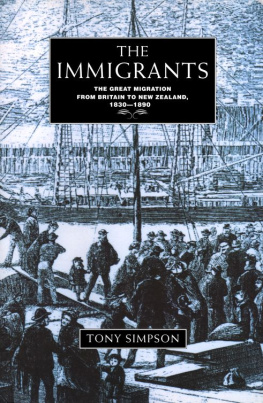

My parents were Scottish. I think they always thought of themselves that way despite their total commitment to New Zealand. I am a New Zealander through and through. Even though I grew up well accustomed to hearing the word home used to refer to England or Scotland, I thought of it simply as a figure of speech or a label. Everyone in those days used that term whether they had been born there or not. If they were going home for a trip you knew where they were going. Not that many people travelled anyway, and my growing up was done in wartime.

My father and his family had left Scotland in the 1920s, in the wave of emigration from British shores after World War I. The eldest in the family, my Auntie Minnie, left first, found a job for herself and then one for my father. He followed in 1922, soon to be joined by their widowed mother and younger brother.

The Macleans lived at Ballachulish on Loch Leven in the Western Highlands, very near the fabled Glencoe of the Macdonald massacre. As a child I often wondered about old documents, kept in a chest of drawers in my bedroom, in which my grandfather was at one time described as a crofter, and at others as a quarryman or storeman. When, many years later, I visited the Western Isles, I realised whyand why so many of its sons and daughters left Scotland. Bleak, barren hills, which must have been able to support only the most spartan subsistence farming, would have been snow-covered for months in winter. What a boon the slate quarries at the head of the loch must have been for the families of the district, providing employment in the off-season.

When Neil, my father, was only 14 his father had a stroke. Dad soon had to leave school and at the age of 16 went to Glasgow, then the world centre of the ship-building industry, to take up an apprenticeship in marine engineeringthe destiny of innumerable Scottish lads at this time. His mother supported the family with a wee shop until her husband died, after which time she and the rest of the family also went to Glasgow.

Ian, the younger son, was apprenticed to a pharmacistthe usual route in those days into many professions, including the law, architecture and accountancy, was to serve your time. He had two older siblings who were supporting the family by this stage, and so he became in conventional terms the successful one or priest of the family, the one of whom Mother was most proud.

There is a parallel here with my mothers family, with whom the Macleans became friendly in Glasgow. The three daughters of John and Catherine Macpherson all left school young and went into office jobs as shorthand typists. The only son, again the baby of the family, went on to university, completed an MA and was accepted into the ministry of the Scottish Presbyterian Churchliterally, in this case, the adored priest in the family.

Exactly when the decision was made to leave Scotland I dont know, but it was part of an already established and ongoing pattern for the Scots and Irish. Nor do I know whose decision it was. Why do we never ask our parents these questions while they are still around to give us the answers?

My cousin Margaret (Auntie Minnies daughter) and I have tried to piece together various bits of our whakapapa with limited success. The versions vary, but it is certain that some other relatives had already settled in New Zealand after World War I and Auntie Minnie was persuaded to come too. She got a job in the office of the Te Awamutu dairy factory, which was managed by a handsome, divorced Dane, with two daughters, whom she eventually married. She arranged a job for my father, and he too made plans to set out for New Zealand. As a marine engineer, he had been to New Zealand at least once before. He was unsure whether to make a new life here or in Argentina, where a number of Scots had also gone, but decided that New Zealand would be easier as the population did speak a sort of English.

Family legend has it that when Dad went to say goodbye to the Macphersons on the eve of his departure for New Zealand the eldest daughter Helen cried and fainted, whereon he declared his affection for her and they became engaged to be married. I certainly never heard this from either of them, but then in that generation one didnt learn anything much that was personal. It was a much more reticent era. Perhaps the story is true. My mother was certainly capable of staging just such a drama!

It would be nice to think that this was a moment of great passion, but Im afraid Im cynical enough to think it more likely that she saw a handsome and eligible man slipping out of her orbit. Hers was, after all, a generation of women for whom potential partners had been wiped out in the slaughter of World War I. A healthy, attractive man was a valued and scarce commodity in those post-war years, and at 26 surely her thoughts were on marriage and family? Typically, neither of her sisters ever married. Ours was the generation with Maiden Aunts in most families. According to the cousinly source of these stories, it had always been thought that Katy, the second sister, would make a match with Neil Maclean.

It was six years before Helen followed Neil to New Zealand and they were married. Ive never clearly understood the reasons for the long hiatus, but it was almost certainly a matter of money. I do know that during that period, Ian, Dads brother, became very ill with appendicitis, which turned into peritonitis. He was hospitalised for over a year, during which time Dad footed all the bills. No antibiotics in those days to cure infection; no social security to cover the costs of medical care. I do know for a fact that it took my father many years to pay all the debtsbut pay them he did.