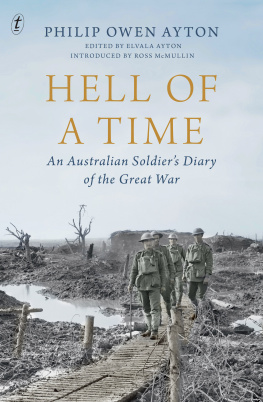

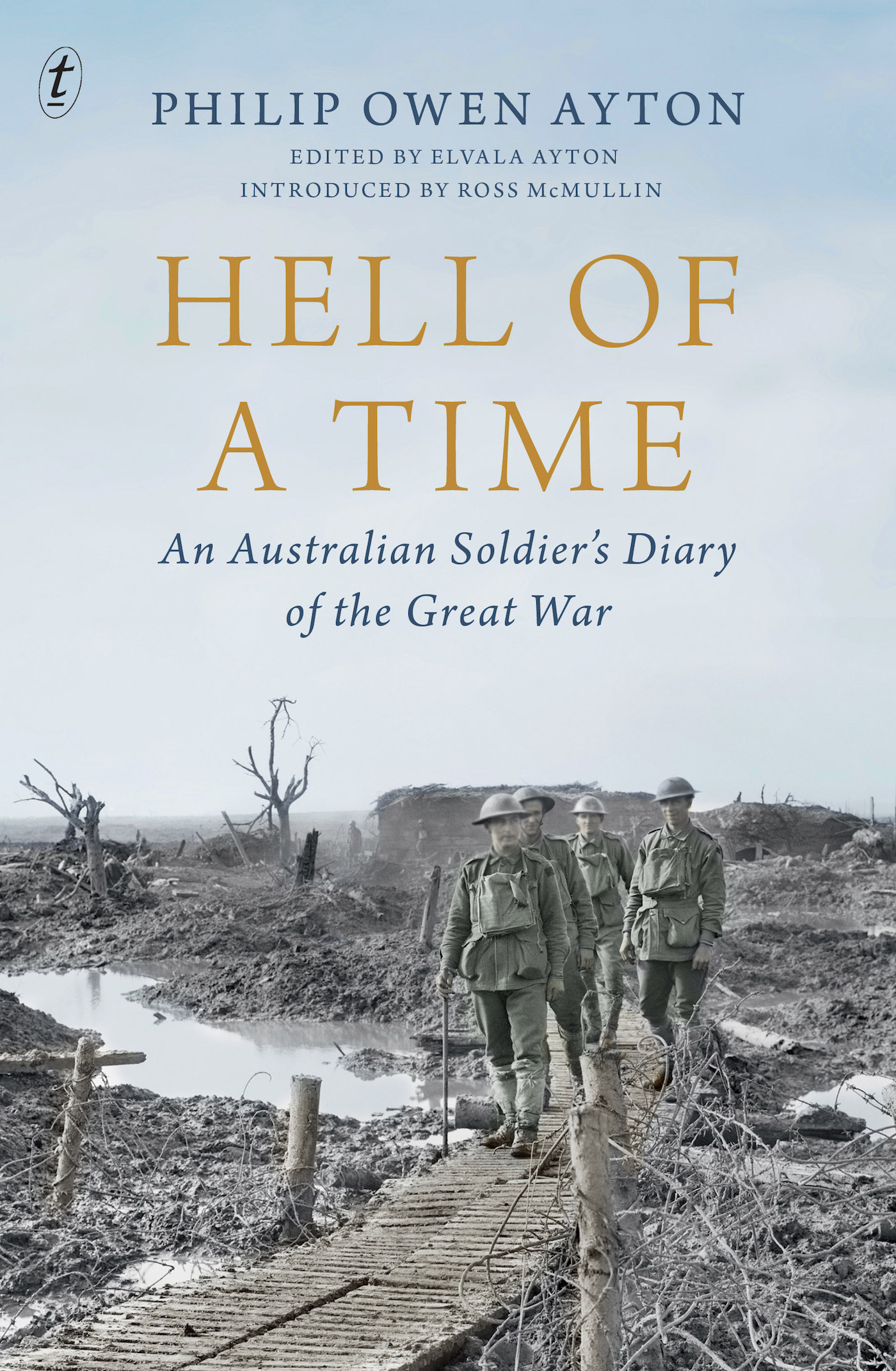

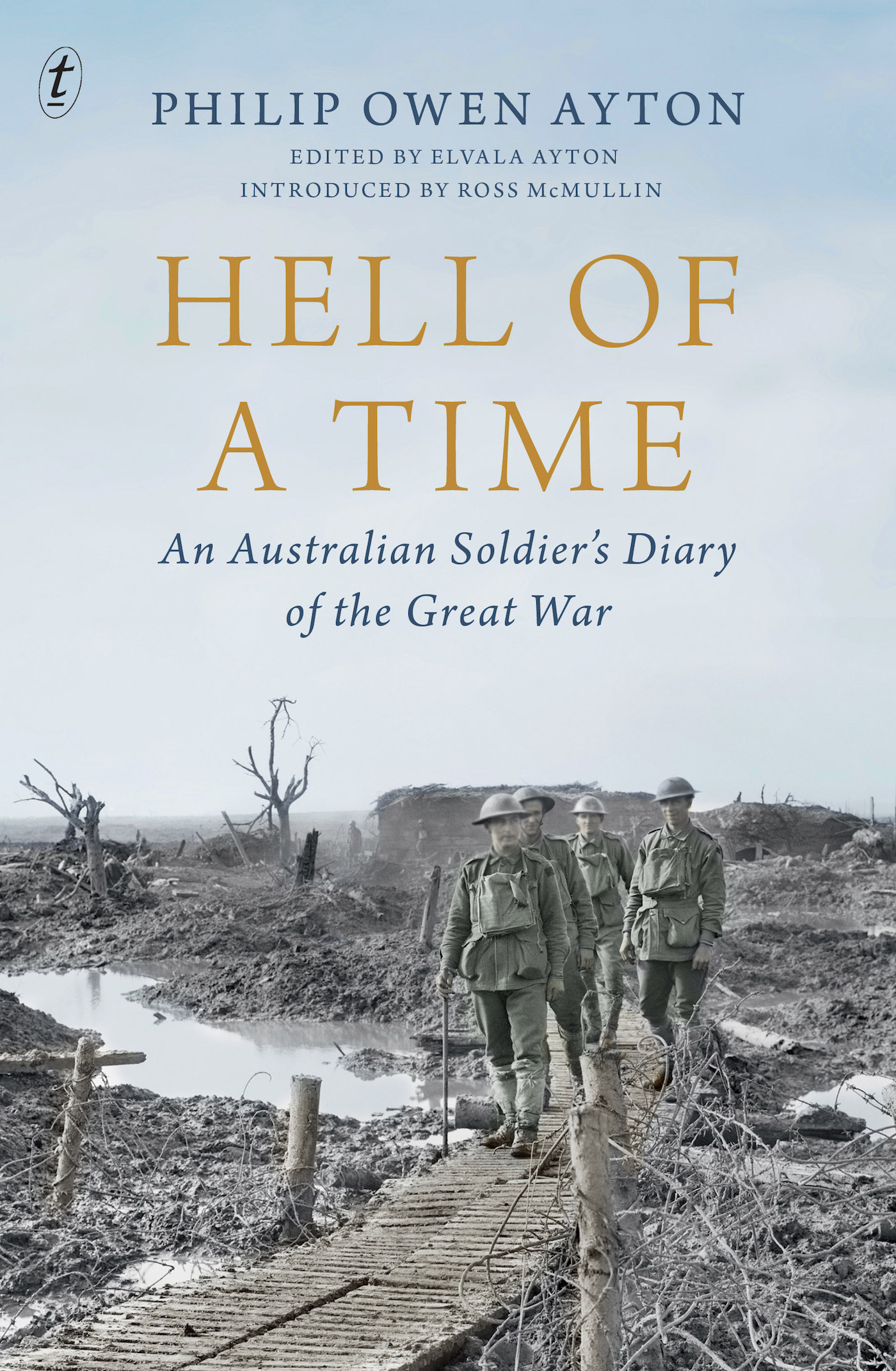

Philip Owen Ayton was working on the Sydney tramways when the call to join the fight against Germany came. Keen for action, he found himself in the First Field Company Engineers in the First Division of the Australian Imperial Forces.

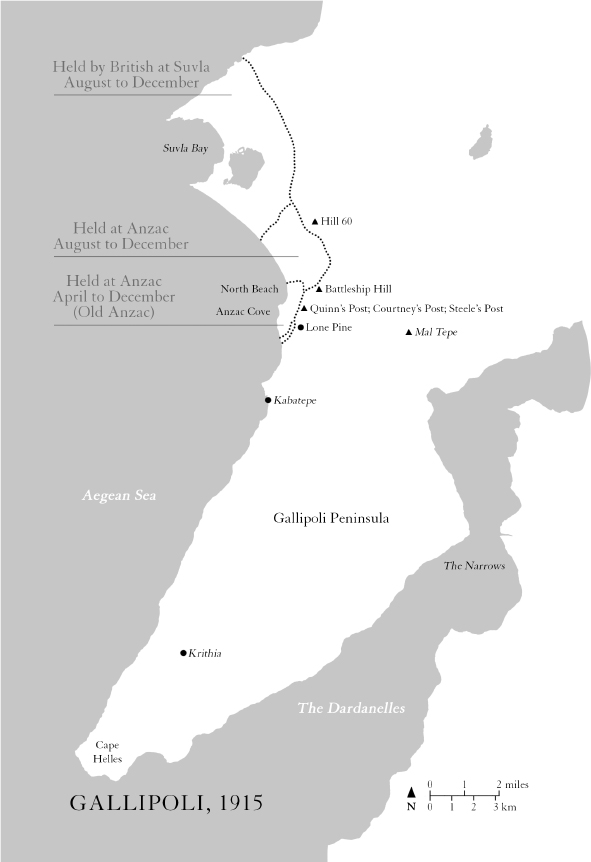

Shipped to Egypt, Ayton soon after took part in the Gallipoli landing. I would not have missed this for anything, he wrote to a friend. Badly injured, he was sent to England to convalesce and from there joined the campaign in France, where he saw out the war.

From the start, Ayton kept notes of his experiences, which he would write up in a diary. Plucky, charming and self-deprecating, this son of the new nation records the horrors of trench warfare and his off-duty adventures in Cairo, London and Paris.

This remarkable story is now published for the first time, a century after the wars end. Accompanied by a postscript by one of Aytons sons and Aytons poem about the Gallipoli campaign, A Hell of a Time is a vital and compelling account of the Great War.

In memory of Philip Owen Aytons younger brotherWalter (Watty) Cecil Ayton, who served with him in World War I and was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal for bravery, joined the military again in World War II, and was killed in the Western Desert Campaign against Rommels forces and later buried in the Benghazi Commonwealth War Cemetery

And in memory of Philip Owen Aytons two sons, Colonel Philip John Ayton and Lieutenant Owen Roy Ayton, who both served their country in World War II

CONTENTS

The race is not to the swift,

nor the battle to the strong

but time and chance happen to them all.

ECCLESIASTES 9:11

Hundreds of Australian personal narratives of World War I have been published, but few more vivid and compelling than this one.

Philip Owen Ayton, a twenty-five-year-old tramways worker, enlisted in Sydney soon after war was declared, and went right through the conflict. He kept notes of his daily experiences and from time to time wrote them up in five notebooks as a diary.

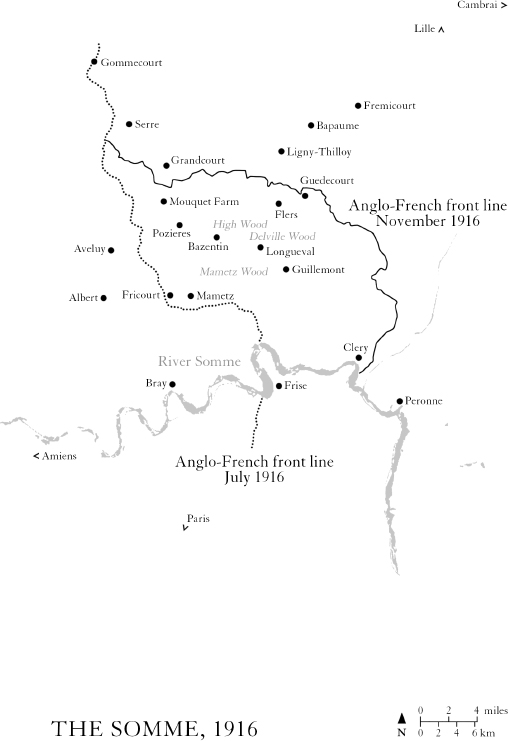

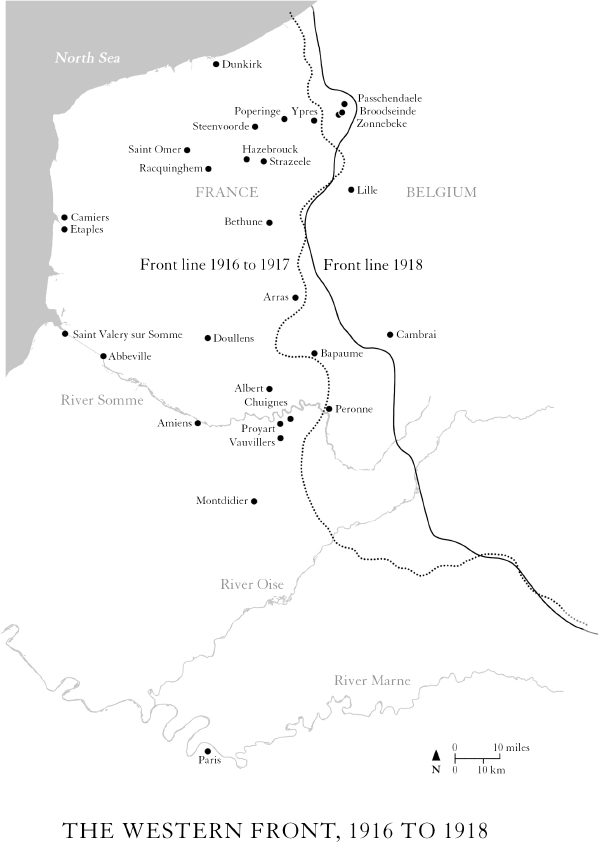

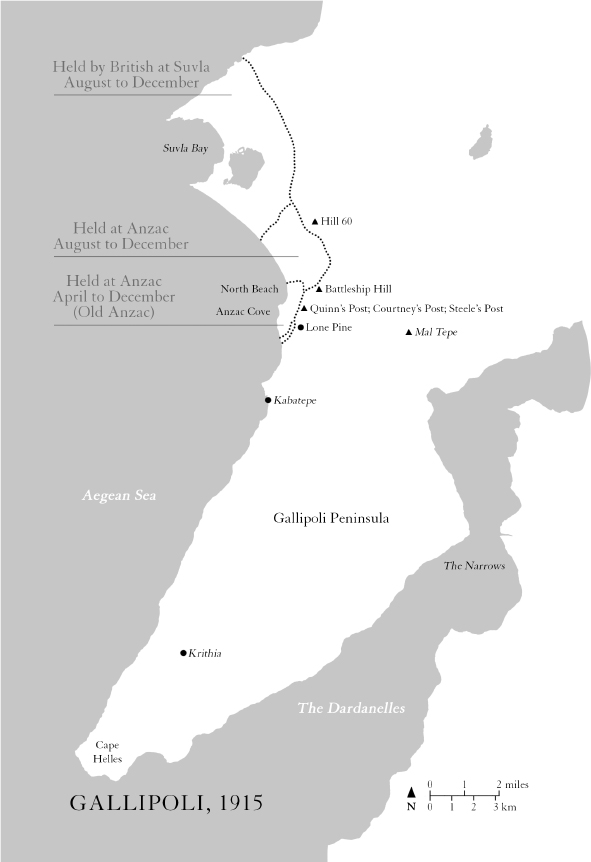

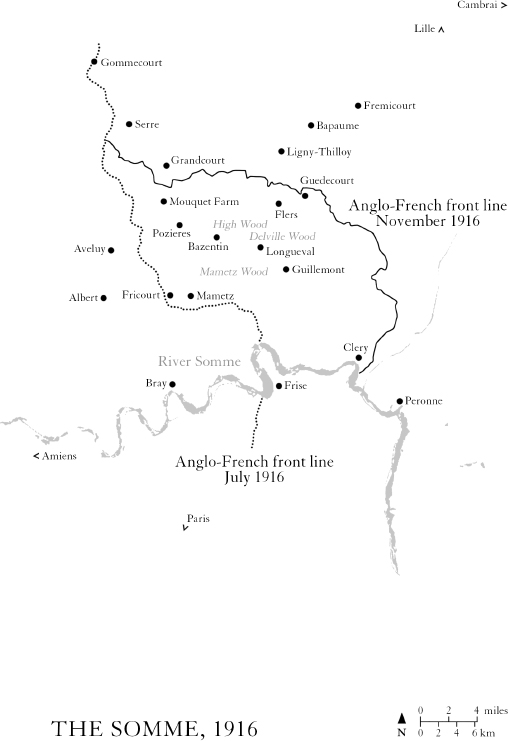

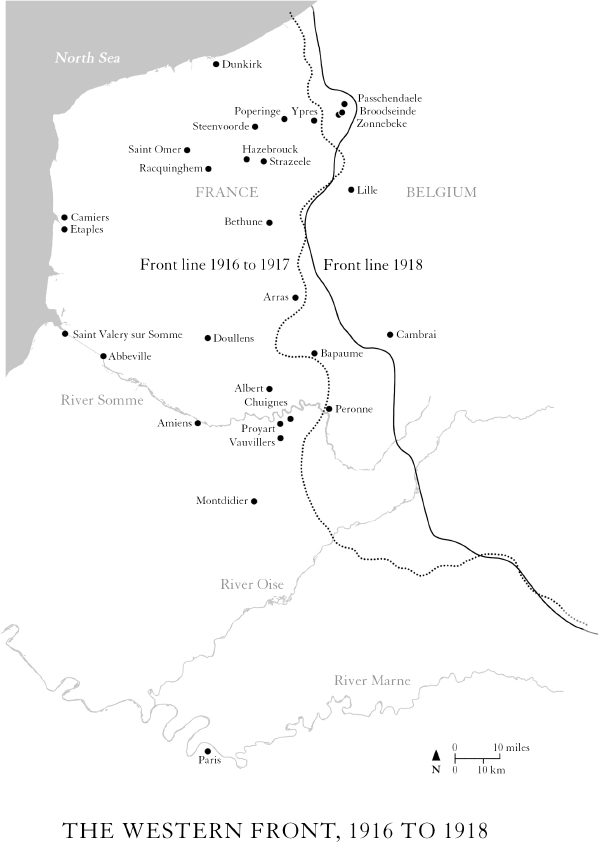

Ayton knew all about the real war. He was at the Gallipoli landing, at Pozieres and Flers, at Broodseinde and Proyart. He endured the ordeal at Steeles Post, the ghastly 191617 winter and four wounds in a day at Mouquet Farm (yet kept going). He knew what it was like, and his sparkling chronicle constitutes a superb record of this momentous era for his nation and the world.

Ayton enlisted in the 1st Field Company of Engineers, and his illuminating coverage of what sappers did is a feature of his diary. Whether it was making roads and piers at Gallipoli, rebuilding boggy trenches under shellfire at the Somme, creating new bridges and tunnels and dugouts, or repairing sections of railway track against the clock so urgent trains were not delayed, Ayton describes it all with evocative authenticity in an engaging, down-to-earth style. His crisp, terse sentences create a natural narrative flow and build page-turning momentum. The reader is there in the trenches with Ayton and his comrades as the shells rain down and they rush to don their gas masks.

Aytons account of the Gallipoli landing narrates what he went through in graphic detail. He felt very lucky to be alive to write it. Soon afterwards he was evacuated when shrapnel injured his knee. He recovered and returned to Gallipoli, but almost died when a further wound led to internal trauma that was misdiagnosed as appendicitis. Recovery took longer this time, but he was back with his unit in time for its memorable journey from Egypt to the Western Front. The nightmare of Pozieres soon followed. For Ayton it was an inferno of hell, with so many awful narrow escapes that he accepted that his death was inevitable. Somehow he survived.

Dedicated and brave, Ayton was a highly effective front-line soldier. He displayed admirable ability and leadership in numerous hot spots. Under-recognised in awards and promotion, he remained diligent and unembittered. Still only a corporal after three years, he was belatedly assigned to an officer training course. He decided to switch to the infantry, and after qualifying as a lieutenant joined the 4th Battalion, which remained his unit until the Armistice. His splendid account of his role in the battle of Proyart in August 1918 underlines the sustained quality of his diary.

A few of Aytons close mates and his younger brother Watty are named, but he preferred not to identify officers, even those he revered. When Pompey Elliott, a renowned Australian leader, had a celebrated duel with a Turk in a murky Gallipoli tunnel, Ayton was directly involved in a prominent role, yet his gripping account of the incident is reticent about the identity of the famous commander: Perhaps I had better not mention his name here, but he was a great soldier and as brave as they make them. We all greatly admired him.

Elliotts willingness to name names in his letters and diaries helped to make his forthright, controversial and emotional narrative of the war so riveting. Ayton, on the other hand, had different aspirations for his diary: it would only refer to myself and what I saw myself in my immediate vicinity. His unwavering focus was not on the wider war and those running it but on what he and his men did, and what it was like to be there. Assessments of identified commanders were, he evidently felt, gratuitous and inappropriate.

In fact, Ayton was close to Elliotts 7th Battalion at Gallipoli at other junctures. His diary records his clear view of the first boatloads of Elliotts unit rowing themselves ashore at the landing: a perfect hail of fire burst upon them from rifles and machine guns and riddled the boats, which was awful to seefew of them reached the beach alive.

A few months later, in July, Ayton and his sapper comrades were with Elliotts battalion at Steeles Post. While they were to endure much worse shellfire at the Western Front, he and his mates had a terrible time occupying Steeles alongside Elliotts men. Because bombardments in France were so appalling, there has been a tendency to dismiss the shellfire Australians encountered at Gallipoli as negligible, but Aytons diary (and Elliotts letters) confirm that this Steeles stint was particularly harrowing. All you could do, according to Ayton, with these monsters crashing down and inflicting casualties day after day, was

wait for the next shell to come and bury you, perhaps kill you outright. We could do nothing. Dugouts were no good to these shells. The suspense was awful between each shellI didnt mind shrapnel or bullets but those heavy shells gave us no chance at all.

Ayton is equally frankand entertainingabout his activities on leave. The severity of his second Gallipoli wound prompted doctors at Malta to decide that he should be sent back to Australia for prolonged recuperation, but he resisted this strenuously, in part because he yearned to visit Britain. The doctors eventually relented and arranged for Ayton to recover there. He was thrilled by his first glimpse of Londons magnificent buildings: My ambition was realised. I was standing in the heart of the greatest city in the world. Visits to Paris and Versailles generated similarly rapturous responses.

Next page