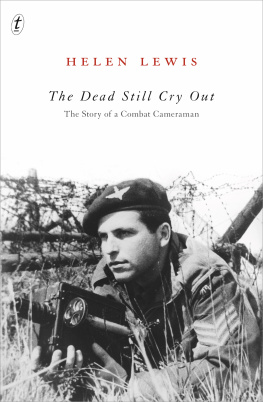

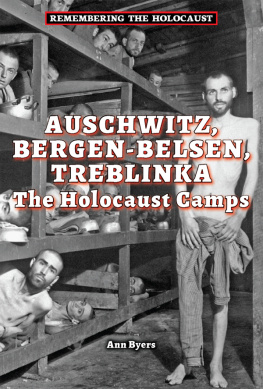

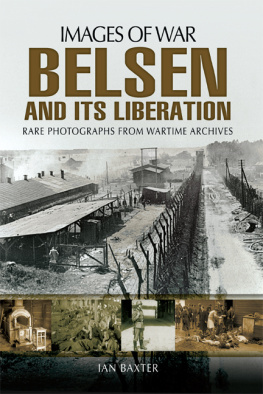

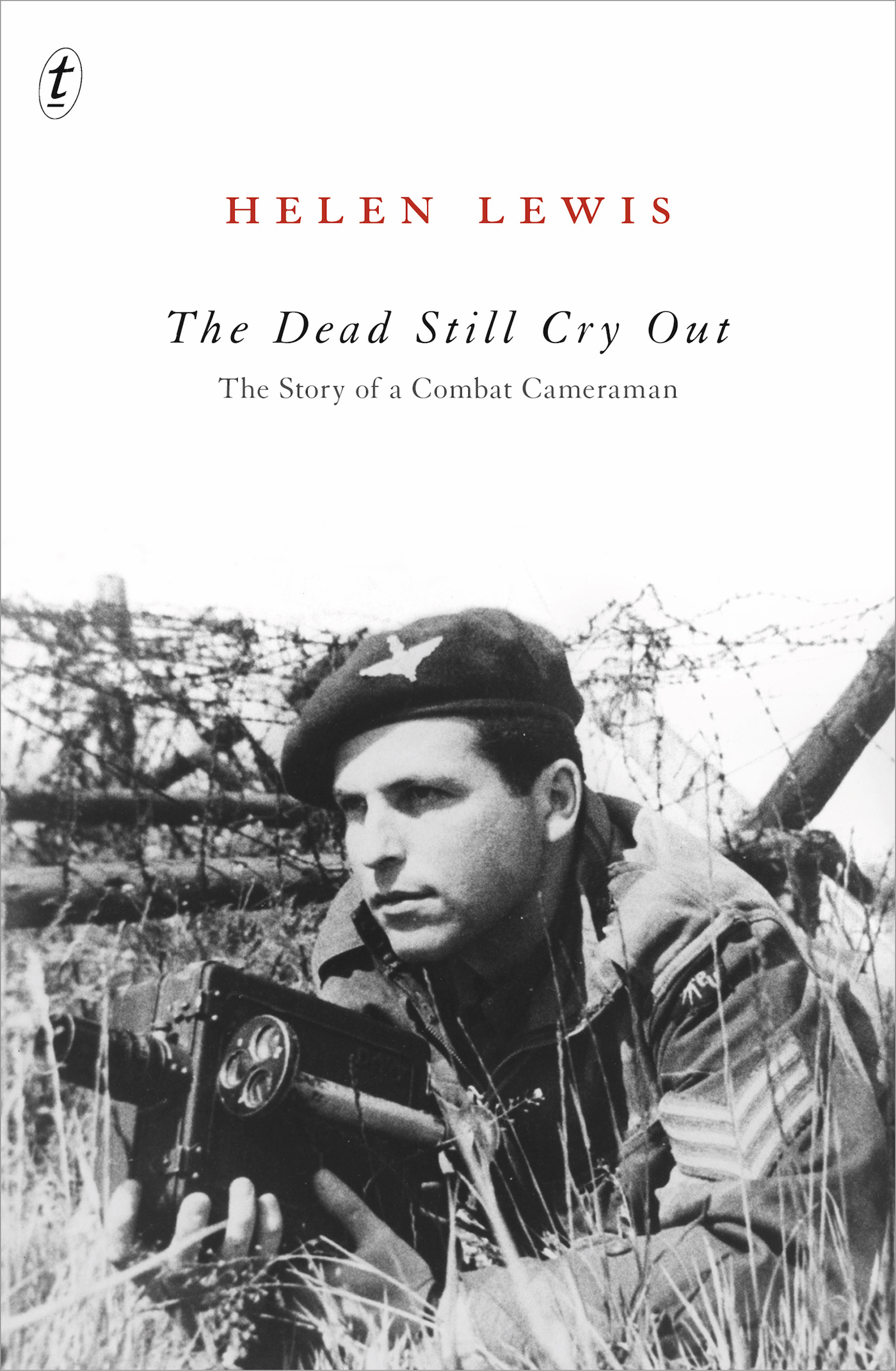

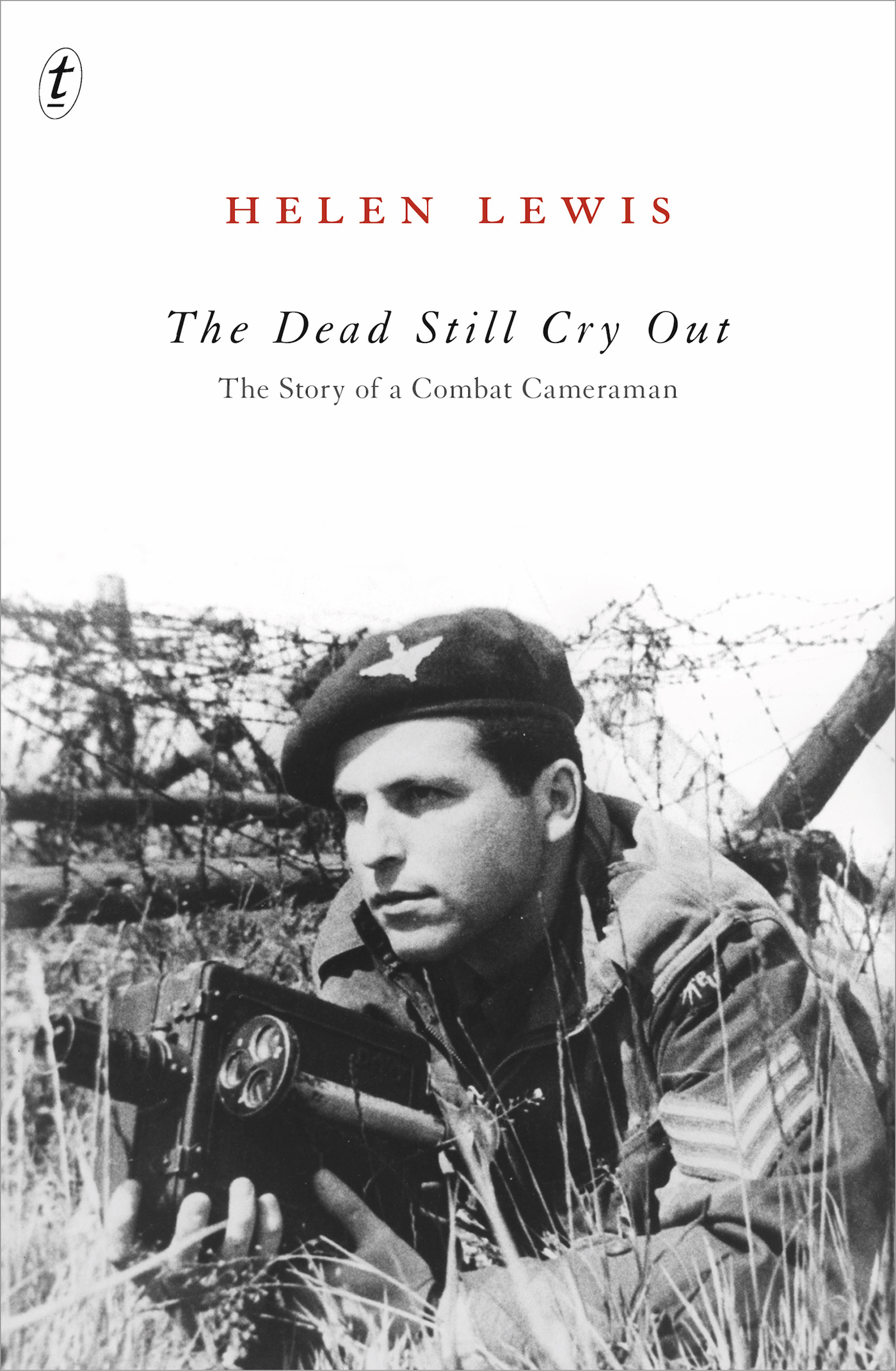

Helen Lewis was just a child when she found an old suitcase hidden in a cupboard at home. Inside it were the most horrifying photographs shed ever seena record of the atrocities committed at Bergen-Belsen. They belonged to her father, Mike, a British paratrooper and combat cameraman who had filmed the camps liberation. Those first images of the Nazis crimes, shot by Mike Lewis and others like him, shocked the world.

The child of Jewish refugees, Mike had grown up in Londons East End and experienced anti-Semitism firsthand in the England of the 1930s. In The Dead Still Cry Out, his daughter uses photographs and film to reconstruct Mikes early life and experience of the war, while exploring broader questions too: what it means to belong; how history and memory are shapedand how anyone can deny the Holocaust in the face of such powerful evidence.

This mesmerising account of a daughters quest to recreate her fathers life as a combat cameraman sharpens our focus on what it means to bear witness to the unprecedented horrors of the Holocaust and its imprint on human history. Mark Raphael Baker

Dedicated to the men of the

British Army Film and Photographic Unit

We had wanted to show you truth, but truth photographs badly.

We had wanted to show you hope, but we could not find it.

HARRY BROWN, POEMS, 1945

In reconstructing my fathers story I have, for the most part, used only those photographs he chose to keep, reflecting what was important to him about his war experiences.

Of the many photographs in this book, eleven cover the liberation of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and are graphic evidence of the atrocities committed there.

The reproduction of these images and others like them over the years since the Second World War has provoked much discussion and controversy, and there are those who would argue that we should not view them at all.

I am not one of them, but neither do I advocate for the widespread dissemination of these images. For me, context is the key, and I feel their reproduction in the framework of this story is appropriate. I hope readers will understand why by the time they finish this book.

I am aware of the profound distress that these images and details of the narrative may cause, but I think that sometimes we need to be disturbed.

Helen Lewis

I am playing in a small cupboard under the incline of the stairs, a place where the bric-a-brac of family life is kept and the place of my imagining games. Today I am Lucy in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, looking for a door to a magic land. I open a battered grey and blue metal suitcase, rifling through the layers of papers and documents. I pull out a brown foolscap envelope and break the seal; five huge black and white photographs spill out. I stare at each photograph for some moments and then return them to the envelope, resealing the flap and replacing the envelope among the layers in the suitcase. I shut the lid, click the catch shut and sit on the suitcase, hands pressed beside me. I make no sound, and my face remains a mask. I tell no one what I have seen.

Did I really sit like that on the suitcase, or did I kneel in front of it, palms flat on the lid, as if holding it shut? I am uncertain now. How do I know my face was a mask? I remember the monstrous images, and a nameless something churning my stomach, and guilt that I had seen what was not meant for me. Sometimes when I recall this moment it seems like it happened to some other child.

In a sense our parents are born to us out of our earliest memories of them. My father appears to me as a tall man in a dark suit already thickening into middle age; hard to imagine that he was an elite paratrooper during the war. When I was very young, I asked him what he would do if his parachute did not open.

Id go back and get another one, he said.

And what did you do when you landed?

I shot off all my ammunition at once so that I could run faster.

I did not believe him, but the flippancy of his responses somehow barred further conversation.

Old memories have been surfacing lately, things I have not thought of for years: about the war, my parents, and our family. They play again sporadically like sequences from an old family movie, unsettling me.

My brother Jeff is lifting me up and sitting me on top of a rough stone wall to watch him play. I must have been about three. The wall is in front of the house where I was born, a semi-detached in a place called Chadwell Heath, in east London. I sit there uncomfortably, the sharp edges of the stonework digging into my bare legs and through my shorts. I would like to get down but it is a long way to the ground and I am not quite sure how to do this. Also, I am enjoying being part of his game, if only indirectly. He is five years older than me and my sister Caroline is three years older than him. I am always running after them trying to keep up and am baffled as to why I cannot do the things that they can. My sister is an amazing being to me, she can read and write and paint. I try to copy her.

My sister is teaching me to skate on the back terrace of our house. I am holding on precariously behind her, being towed. Then we fall backwards, she on top, knocking the breath out of me. Later, I am lying tucked up on the couch and the doctor has been, just in case. My mother is worried because I have not said a word since the accident and my father, who has been away for months filming in Canada and the US, is coming home today, and there is much anticipatory excitement. In time I will come to feel this too, and look forward, as my sister and brother do, to the wonderful presents that he brings for us, and his stories, but this time when he arrives I feel shy. He pinches a toe sticking out from under the covers. I know he is my father, but he has been away so long that he is unfamiliar.

I was a little over four when our family moved to a brand-new house in the hamlet of Little End in country Essex. My father named it The Old Well because the builders discovered an ancient well under a flagstone when they demolished the old farmhouse that had stood there. It was a large house; my parents wanted us each to have a room of our own and space to run around in the fresh air. They probably had in mind the terrible smogs that choked and killed Londoners in the fifties.

Most of the time my parents presented a united front to us children, but I knew quite early that my mother did not like my father teasing us. I think she thought it unkind, especially when we were too young to retaliate. He reserved an especially humiliating strategy for when we were shopping together. Regardless of what the shop sold, when he was asked, And is there anything else, sir? he would reply, Yes, do you have one of those things for taking stones out of horses hooves? Clearly he thought this very amusing. I would hide my face in his leg with deep embarrassment as the shop assistant feigned laughter, looked confused or simply tried to ignore the remark. Sometimes before walking into a shop I would plead with him not to ask the question. When I got older I would move away and inspect something in another part of the shop.

His silliness could be frustrating too when I wanted straight answers to my important questions about the world. Once, in answer to my plea for seriousness, he asked a little miffed, pouting like a child, Do you really want me to be a serious dad, just like all the other dads? That set me back, because I had to admit that, on balance, I really did not want a serious fatherand besides, there were moods that came upon him sometimes, as if a light went out inside him, leaving a dark presence that would chase away the playful child-man. Then he would become intolerant of anything that disturbed his peace and might burst out angrily at one of us children. At times I would spot a kind of tension building in his neck and jaw before the mood came upon him, and although there was often no obvious connection to anything I had done, I somehow felt implicated. No, it was better that he was a silly dad.

Next page