For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

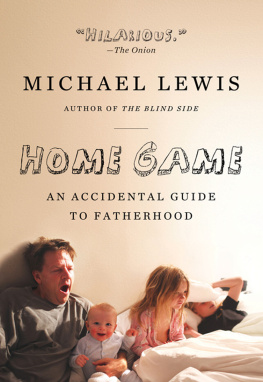

1. Lewis, Michael (Michael M.) 2. FathersUnited States

Biography. 3. FatherhoodUnited States. I. Title.

HQ756.L479 2009

306.874'2092dc22

[B]

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

If you dont want to see it in print, dont do it.

INTRODUCTION

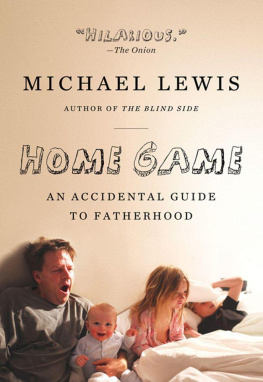

I INHERITED FROM my father a peculiar form of indolencenot outright laziness so much as a gift for avoiding unpleasant chores without attracting public notice. My father took it almost as a matter of principle that most problems, if ignored, simply went away. And that his children were, more or less, among those problems. I didnt even talk to you until you went away to college, he once said to me, as he watched me attempt to dress a six-month-old. Your mother did all the dirty work.

This wasnt entirely true, but itd pass cleanly through any polygraph. For the tedious and messy bits of my childhood my father was, like most fathers of his generation, absent. (News of my birth he received by telegram.) In theory, his tendency to appear only when we didnt really need him should have left a lingering emotional distance; he should have paid some terrible psychological price for his refusal to suffer. But the stone cold fact is his children still love him, just as much as they love their mother. They dont hold it against him that he never addressed their diaper rash, or fixed their lunches, or rehearsed the lyrics to Im a Jolly Old Snowman. They dont even remember! My mother did all the dirty work, and without receiving an ounce of extra emotional credit for it. Small children are ungrateful; to do one a favor is, from a business point of view, about as shrewd as making a subprime mortgage loan.

When I became a father I really had only one role model: my own father. He bequeathed to me an attitude to the job. But the job had changed. I was equipped to observe, with detached amusement and good cheer, my children being raised. But a capacity for detached amusement was no longer a job qualification. The glory days were over.

This book is a snapshot of what I assume will one day be looked back upon as a kind of Dark Age of Fatherhood. Obviously, were in the midst of some long unhappy transition between the model of fatherhood as practiced by my father and some ideal model, approved by all, to be practiced with ease by the perfect fathers of the future. But for now theres an unsettling absence of universal, or even local, standards of behavior. Within a few miles of my house I can find perfectly sane men and women who regard me as a Neanderthal who should do more to help my poor wife with the kids, and just shut up about it. But I can also find other perfectly sane men and women who view me as a Truly Modern Man and marvel aloud at my ability to be both breadwinner and domestic dervishdoer of an approximately 31.5 percent of all parenting. The absence of standards is the social equivalent of the absence of an acknowledged fair price for a good in a marketplace. At best, it leads to haggling; at worst, to market failure.

A brief thought experiment: Two couplesBob and Carol, Ted and Aliceget together for dinner. They havent known each other for long, and will discover during this dinner that they have cut slightly different parenting deals with their spouse. Carol and Bob split their parenting duties 60/40; Alice and Teds split is more like 80/20. Bob and Carol think children shouldnt watch the Disney Channel; Ted and Alice think the Disney Channel, properly used, can be an excellent babysitter. After an otherwise delightful dinner they:

a. Go home and leave unmentioned how differently the other couple parents and divides the parenting chores.

b. Acknowledge their differences but agree, privately, to disagree. Parenting chores arent chores at all: theyre a joy! Plus, theres more than one way to skin a cat, or raise children.

c. Go home and haggle. Not right away, of course. Alice gets home and stews and promises herself she wont say anything. But at some point she fails to suppress the soundtrack in her head. I really like the idea of reducing the influence Disney has on our family, she says. Or: Its nice the way Bob drives the kids to school and frees up Carol in the mornings. Meanwhile, down the block, Bob is wondering why the hell he has to drive the kids to school every morning. Just before they agree that they wont be having sex anytime soon, he says, Alice really is a great mom, isnt she? And a funny thing happens: These two couples never see each other again. They had agreed to get together for dinner but somehow it never happens. Teds busy; Carol cant make it.

If you answered (a) or (b) you can skip the next two paragraphs.

Heres the question: Why should social interaction with couples who parent even slightly differently so quickly lead to internal strife? How can putatively important and deeply considered decisionshow to parent, and what role the father should playbe so easily undermined by casual contact with a different approach? Why should even fictional representations of different parenting styles be an invitation to argue about who should do what?

One answer: In these putatively private matters people constantly reference public standards. They can live with their own parenting mistakes so long as everyone else is making the same ones. They dont care if theyre getting a raw deal so long as everyone is getting the same deal. But there are no standards and its possible there never again will be. Were all just groping, then lying about it afterward. As a result, the primary relationships in American family life have acquired the flavor of a Moroccan souk.

I began keeping a journal of my experience of fatherhood seven months after the birth of our first child. The reader will quickly see that I didnt set out to write about new fatherhood. I set out to write about Paris, but Paris was overshadowed by a seven-month-old baby. Most of what follows was written in the hazy, sleepless, and generally unpleasant first year after the birth of each of my three children. Most of it was also written within a few days after the incident reported. I found pretty quickly that any thoughts or feelings or even dramatic episodes I didnt get down on paper immediately I forgot entirelywhich was the first reason I began to write stuff down. Memory loss is the key to human reproduction. If you remembered what new parenthood was actually like you wouldnt go around lying to people about how wonderful it is, and you certainly wouldnt ever do it twice.

Which brings me to the main reason I kept writing things down: this persistent and disturbing gap between what I was meant to feel and what I actually felt. Expected to feel overcome with joyIts a boy! You must be so happy!I often felt puzzled. (I shouldnt be just as happy if it was a girl?) Expected to feel outraged, I often felt secretly pleased; expected to feel worried, I often felt indifferent. (Its just a little blood.) For a while I went around feeling a tiny bit guilty all the time, but then I realized that all around me fathers were pretending to do one thing, and feel one way, when in fact they were doing and feeling all sorts of things, and then engaging afterward in what amounted to an extended cover-up. As this book is largely a collection of stories, Ill use one that didnt make it in to illustrate the point. Cut to the journal