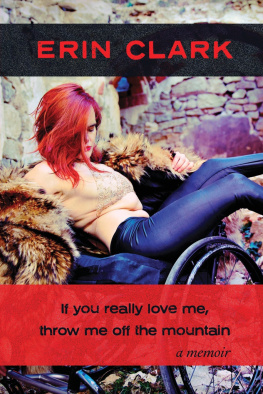

IF YOU REALLY LOVE ME,

THROW ME OFF THE MOUNTAIN

If you really love me, throw me off the mountain Erin Clark.

Published by EyeCorner Press 2020.

Designed and typeset by Camelia Elias.

Photograph on the cover by Eli Mora, by kind permission.

ISBN: 978-87-92633-55-2

EBOOK ISBN: 978-87-92633-56-9

August 2020, Agger, Denmark

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, without written permission from the publisher and the copyright holder.

EYECORNERPRESS.COM

For my social media community.

Especially those of you who kept asking me to write a book.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Memory is alive. It flows and fluctuates with time and perspective. A book does not. I fixed all my perceptions of the people and events in my life to a page and a time. I did my best to render them fairly and honestly and with love. I changed a few names where it was appropriate. If you see yourself reflected in these stories, I hope you feel my respect and appreciation.

A few sections have appeared in other forms in literary journals or as Instagram posts and Im grateful to my readers and editors and publishers along the way.

My deepest gratitude to Mayumi Shimose Poe and Jacob Sheen, Allison Williams, Laura Von Holt, Carolyn Camman, Jessica Lipnack, Brooke Roberts Eikmeier, Sarah Hosseini, Batia Stolar, and Misha Bower whose support and influence on the drafts and iterations of this work from when it was merely an idea to its final shape were essential. If I sent you a piece of writing, and you told me to keep going, you have helped more than you know.

Thank you to Oranjemund, Vilaseca, Algodonales and London, Ontario for being the places that held me as I wrote.

Thank you Camelia for your magic. Publishing with you is one hell of a romantic adventure and has brought my dream to life exactly as I dreamt it.

Thank you Zero Gravity for teaching me to fly and buying my groceries and fixing my wheels and letting me be part of the team even if my greatest contribution was as a bad influence on your English.

To mom, thank you for letting me tell whatever stories I wanted and needed. I hope you feel freer, too. Thank you also to my brothers.

And finally, thank you to all the disabled writers, philosophers, artists, activists, and educators who came before me and taught me how to take up space in this world.

I have always had the challenge of balancing the desire for everyone to get out of my way with the reality that I need people to get me where I want to go. Thankfully, my life has been full of people who somehow made more sense of that than I ever could and did both: helped me and got out of my way. In every place that I found barriers, I found freedom fighters and liberators and people who encouraged and shared in my adventurous spirit. Many whose names I never even knew. I hope this book will do the same for others as has been done for me: give confidence, permission, space and encouragement and then get out of the way.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Please, Let Me on the Plane

Windhoek, Namibia, January 2019

T wenty minutes before boarding, the gate agent informs me that they wont be letting me on the plane.

Im in the tiny local airport terminal in Windhoek,

Namibia. The plane is headed to Oranjemund, a diamond-mining town on the southern edge of the country.

My bags are stowed on the plane, Im past security, Im mid-sip of a latte I bought to access WiFi in the cafe, my eye on my planes gate.

Why not? I ask with mild alarm. Is the flight cancelled and this is my personal announcement?

Because we cannot assist you, the gate agent says hesitantly, waiting for me to piece it together.

I rush another sip of latte and purse my lips. I can get myself up the steps, I counter.

You cant, he insists.

I know the issue is imagination. The airport staff see me, wheelchair, stairs, and throw up their mental hands in defeat. The only solution they can come up with is to not let me board.

I had reached a summit of 2,200 metres in the Himalayas on my hands and knees that year as a birthday adventure. This tiny Namibian plane is not out of my range.

The commissioner wants to discuss it with you, the agent says, and indicates that I should follow him back through security. My instinct is to stand my ground. But the agent is caught between us with no power in the situation me insisting on my autonomy, the commissioner on his authority.

As I follow, a familiar fear of a bad outcome squeezes my chest. My phone only works in the caf. How will I arrange new accommodations in Windhoek or to catch a bus nine hours through the desert to my destination? My bank card isnt working so I cant even get enough cash to pay for a taxi out of the airport. How helpful will the commissioner and his staff be?

The gate agent holds up his hand to stop me, then disappears into an office where I can hear them discuss me.

Could someone talk to me and not about me, please? I call into the office.

Hello, my name is Martin. How are you? says the commissioner. He steps into the hall, towering over me, and invites me into the office.

Hello Martin, Im Erin. Im scared, actually.

Listen, in situations like this, we dont admit people who cant walk onto the plane, he says gently. Maybe the elderly, people with canes, but if you need assistance, we cant let you board. He explains that not only do they lack the equipment to get me on the plane but there are also no safety protocols for getting me off the plane in the event of an emergency. He doesnt mention but I travel frequently so I know that the only procedure for getting a person with a disability off the plane is to have more than one flight attendant ask the passenger to wait, in the midst of an emergency, until all the other passengers have been evacuated and hope someone remembers to rescue them. I have never had the intention of following that procedure.

Just a small edge of the commissioners desk is clear of folders and stacked papers. I reach for it and pull myself upright, all my body weight locked into my shoulders and my elbows. I urge the commissioner to stand, to make his arm a stiff railing, which I grab. I push him forward so I have somewhere to step, showing him how I will pull myself up the steps and to my seat without any assistance.

He feels the strength of my grip and the power in my push as I use his more-than-six-foot-tall frame to move my four-foot-eleven, 95-pound body around his office. He is professional, a calm and thoughtful expression on his face despite the absurd intimacy of this demonstration. He agrees to let me board the plane but warns, The pilot will have to decide in the end. Someone will be with you to carry your things. But you must get on without any help.

I take a second to register that I have convinced him. The tension that had been crawling through my body is immediately relieved. I was willing to crawl across his office floor to show how I could rescue myself, but I didnt expect to change his mind.

My gate agent leads me past the security checkpoint again and out onto the tarmac into the dry blaze of Namibian sun. I sit on the bottom step of the airstairs to pop the wheels off my fixed-frame wheelchair, twist around to reach for the guard rails, and pull my body up, step by step, into the plane. The captain pops his head out of the cockpit to watch. The same muscles that I use as a circus aerialist on the stages of New York get me to my seat.

This isnt the first pilot, conductor, bus driver, or taxi operator who has refused me, but it is the first time I changed a mind.

Next page