Happy Days

My Mother, My Father, My Sister & Me

Shana Alexander

CHAPTER ONE

THE NEST

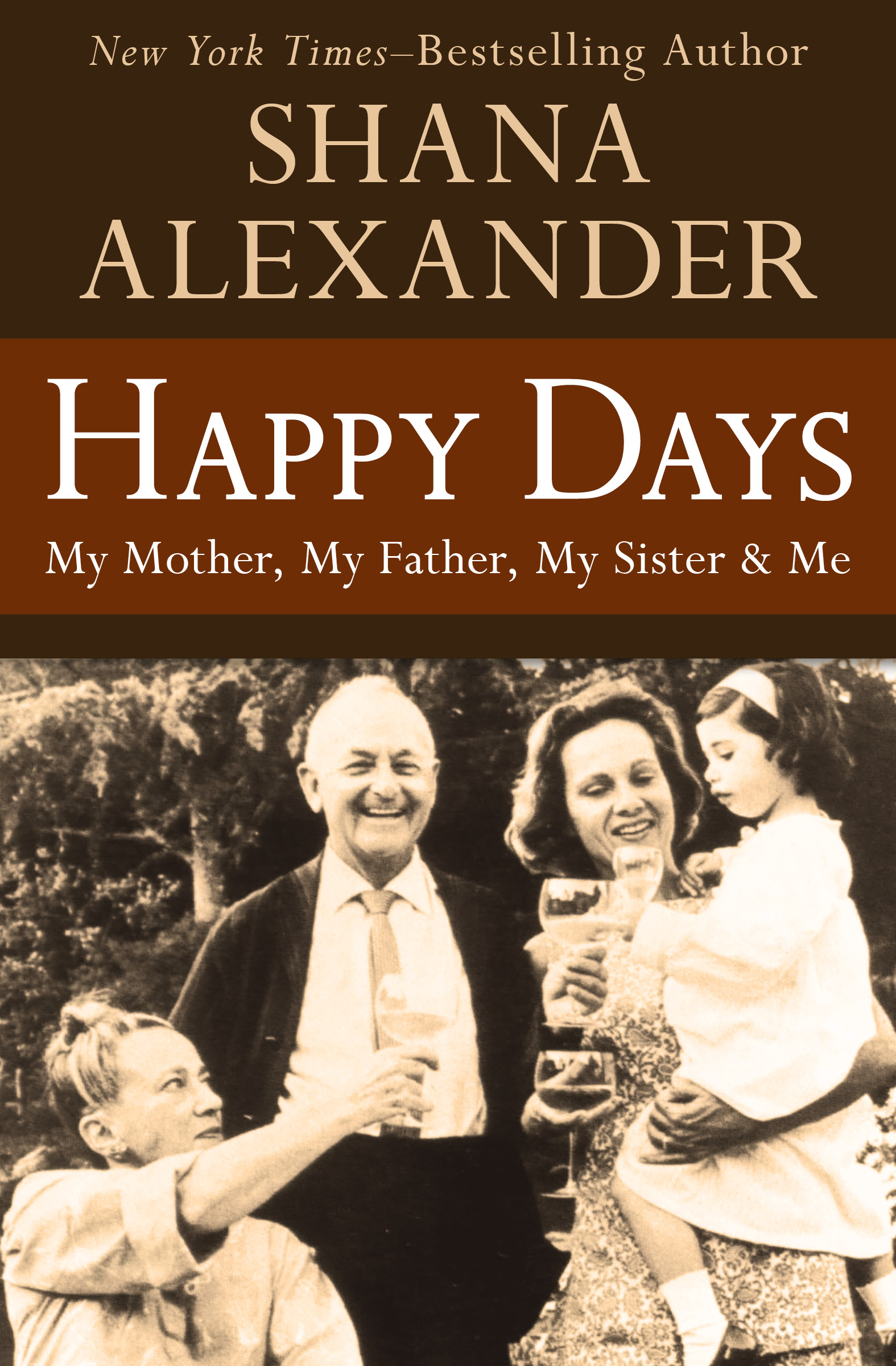

T he first moment I remember is holding his hand and walking down the long, white-tiled hospital corridor. We are going to see my new sister. My eyes follow an inset band of blue tiles level with my fathers shoulders. I am three years old today. It is his birthday too.

The first sound I recall is the scratch, scratch of his razor blade on music manuscript paper scraping out wrong notes. He writes late at night by candlelight on a fold-up Salvation Army organ that Cecelia bought him and put in our bedroom. We cant hear the music because he doesnt need to pump the pedals. He hears it in his head. The scratching goes on for hours, a pleasant sound in the near darkness.

What else? Three bad tastes: oysters, rhubarb, milk of magnesia. The awful German frauleins who cared for us. All the wonderful closets to explore. In the hall closet are stacks of records of Miltons songs, his piles of symphony and opera scores, his collapsible silk hat, our Christmas tree ornaments, and, on the bottom, our bootleg whiskey. Sime Silverman, the burly, rough-voiced editor of Variety, where Cecelia works, brings the whiskey, and never forgets to bring Laurel and me a quart of Louis Sherry ice cream, hand-packed, with little black specks in the vanilla.

Our own closet holds all our smocked English dresses and high-laced shoes, and the beloved Oz books that Grandmother Fanny sends twice a year from Hollywood. My child-size golf bag and clubs hang from a hook. Out of reach on the top shelf is a beautifully dressed French doll as tall as I am. Fanny sent her too, but Cecelia says she is too good to play with. We dont like dolls anyhow. We like our big blackboard, our child-size, simple American furniture: two chairs, work bench, the big revolving globe.

The linen closet outside our parents bedroom holds their bed sheets stacked in scented piles tied with ribbon. Their towels are peach color or turquoise, monogrammed in lowercase letters, cra: Cecelia Rubenstein Ager.

How glamorous our mother is to me, and scary, especially in the mornings, when she wakes up in her black eye mask and reads the papers and sips her caf au lait and smokes a Chesterfield while Milton is still sleeping in the other bed. In the evenings, I cannot wait for them to go out so I can investigate her big closet stacked floor to ceiling like a milliners shop with boxes upon boxes of silk flowers from Paris in every color and variety. Alongside are piles of soft leather gloves in every shade and belts of every material and hue. At the very back in a special bag is her crimson silk velvet evening wrap trimmed with ermine tails, and a thin gown of white silk sprigged with tiny flowers, and a pair of winged sandals woven of gold and silver strips. Over everything floats the fresh, ferny scent of New Mown Hay, from J. Floris, in London.

New Mown Hay was the only perfume she ever wore. Years later, when I visited the shop and tried to buy her some, I was told they no longer made it. All the hay in Europe had been cut down during the war.

About my birth I know only that it started gaily and ended badly for everyone. On the evening of October 4, 1925, Cecelia and Milton had gone with their friend Lou Clayton, Jimmy Durantes manager, to the Club Durante on West 58th Street to catch the new act. When Durante began smashing up his piano and hurling pieces of it at his own orchestra, Cecelia laughed so hard she started going into labor. Milton rushed her to the select Lying-in Hospital off Gramercy Park where Cecelias favorite cousin, Hannah Stone, M.D., was on the obstetrics staff. For the next two days Hannah and Sylvia Yellen, the wife of Miltons lyricist partner Jack Yellen, took turns at Cecelias bedside. Nearly forty hours passed before I was finally born. Sylvia was right there in the delivery room holding Cecelias hand, just as Cecelia had done for her when the Yellens first son was born two years before.

I finally made it with the assistance of a pair of wicked, long-handled surgical spoons, standard tools for a high forceps delivery, that left me with permanent scars under my left eyebrow and along the right side of my neck, and a lifetime sense of having a huge head. The ordeal left Cecelia half-dead, and perhaps not feeling entirely cordial toward her firstborn, or so it was much later suggested independently, by different psychoanalysts, to each of us.

My parents lived then at 157 West 57th Street. Cecelia was in thrall to a fashionable Park Avenue pediatrician who decreed that a bottle is the only sanitary way to feed a baby and that crying is natures way of developing an infants lungs. Hence a crying baby should never, repeat never, be picked up, hugged, or rocked, and so far as I know, she never did it.

After Laurel was born, I remember hearing my parents arguing over these matters. My information about their lives before her birth is next to nil. About all I know is that Cecelias favorite brother, Laurence, two years younger, was killed in a car crash a few months before Laurels birth, and she was named for him. Although our parents were professional writers, neither one kept a journal or diary or scrapbook. They didnt save desk calendars. They didnt keep letters or other memorabilia. No family photographs were on display. Cecelia seemed pathologically disinclined to talk about herself or her early life, at least to her children. Milton loved to reminisce, but not about the person I was most interested in hearing about, George Gershwin.

I knew George Gershwin up close, Milton said to me when he was over eighty and we were discussing the book we intended to write together about Tin Pan Alley. But I wont talk about him. Because unless youre a fellow musician, you wont understand what Im saying. He had talked about him, of course, from time to time over the years, but always in a guarded and extremely protective way.

However, Cecelia and Milton had been good friends of George and Ira Gershwin and the rest of the family. And the Gershwins early aware that they were harboring a genius in their midsthad kept meticulous records and saved everything. Old check stubs, theater tickets, calendars, doodles, and every scrap of paper ephemera has since been catalogued. Much of the little I know about the Agers early years comes from tidbits pieced together from the extraordinarily well documented Gershwin saga.

My first sighting of Cecelia and Milton as a married couple is in June of 1926, when they appear in a well-known photograph of the Gershwins and a couple dozen of their pals at a beach hotel on the Jersey Shore. Their hosts were Albert and Mascha Strunsky, prosperous Greenwich Village landlords and restaurateurs. Soon the Strunskys daughter Leonore, known as Lee, would marry Ira Gershwin or, as Cecelia always put it, would finally get Ira to marry her.

The occasion for the Strunsky photograph was a house party celebrating the sixth wedding anniversary of Lees older sister Emily and Lou Paley, an erudite English teacher and sometime lyricist. The showbiz guests were posed by George, who reclines odalisque-like in the foreground, the Young God recumbent. The couple not exactly snuggling on the top step, left, are Milton and Cecelia.

Did either parent ever mention this picture to me? Not once. I came across it quite by accident nearly a half century later, in a new book lying on the coffee table of their Wilshire Boulevard apartment. The writers were Edward Jablonski and Lawrence D. Stewart, Gershwins biographers. Jablonski lives in New York, and Stewart, an attractive, easygoing man about my age, in California. Id met Stewart once or twice visiting my parents. Twenty years after that, desperate to increase my meager store of data on Cecelia and Milton, Id taken a chance and called him up. It was like stumbling across the Lost Dutchmans Gold Mine. He kept a journal, I discovered, a lifelong habit he picked up while writing his doctoral dissertation on one of the many eighteenth-century litterateurs who buzzed around Dr. Johnson. Over the years Stewart had become as fascinated as I by the Agers and their unique relationship, and each time hed seen them, singly or together, hed noted the occasion in his journal. Furthermore, Stewart is a lifelong musicologist, historian, archivist, and connoisseur of contemporary arts. I can count on the fingers of one hand the people who were a friend of both Cecelia and Milton, and appreciated them equally, and Lawrence Stewart is one. He had also been a close friend of Ira and Lee, at the hub of their extensive Hollywood social circle, and had worked fourteen years on the Gershwin archives. He had helped Ira write his little 1959 masterpiece,