Nutcracker

Money, Madness, Murder: A Family Album

Shana Alexander

For Kirk and Scott Thompson, and Joyce

CONTENTS

1981

THE GREAT GOLD HALL ablaze with lights, the red velvet seats alive with children rows and rows of childrens faces, all upturned, a Christmas candy box of nougats, cherries, caramels, peppermint creams, and almost all of them the shining, scrubbed faces of little girls delectable would-be ballerinas, brushed and shining and trembling. For one month every year during the holiday season, such is the impression looking down from the balcony into the orchestra section of the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center when, night after night and every matinee, the New York City Ballet puts on its Christmas classic, The Nutcracker.

Lights darken, noises dim, Tschaikovskys overture pours fourth in creamy swirls of sound, audible Nesselrode. The gold curtain pleats upward in damask swags to reveal a gay party in nineteenth-century Germanymothers in hoopskirts, dashing, mustached papas, daughters in ball dresses, little boys in velvet suitsall rushing happily about the stage, bowing, curtsying, whirling with glee.

A crooked old man enters, leaning on a stick. The children flock around him. He is Herr Drosselmeier, and he has brought to the party with him a very special Christmas gift, a magic nutcracker. Soon he will tell them a story about it, an elaborate and cracked tale first penned by E. T. A. Hoffman: that is his nutcracker suite. But first he distributes nuts, real nuts, to the eager children. In the Balanchine staging, a restaging of the masters own dream of magical childhood, seven tiny girls in mauve pantaloons cluster around the old mans knees. In fact they are seven infant ballerinas, rigorously chosen, the crme de la crme of very young students at the ballet school which trains many of the dancers who will one day join the Companys corps de ballet, one of the best the world has known.

The seven child ballerinas tease, plead, twirl, cajole. The candy box of audience children holds its sweet breath. To which one of the seven will Herr Drosselmeier present his very first nut? The child ballerinas themselves do not know. Indeed, they have made it a game, a very secret game, just between themselves and the gnarled old man. Which one will he choose tonight? they wonder as they dart enchantingly about. Lately, though, the game has gone flat. Lately he always chooses the same dancer. He always gives the first nut to the tiniest one of them all. She is a grave child who never smiles. She is eight years old. Her name is Ariadne.

1978

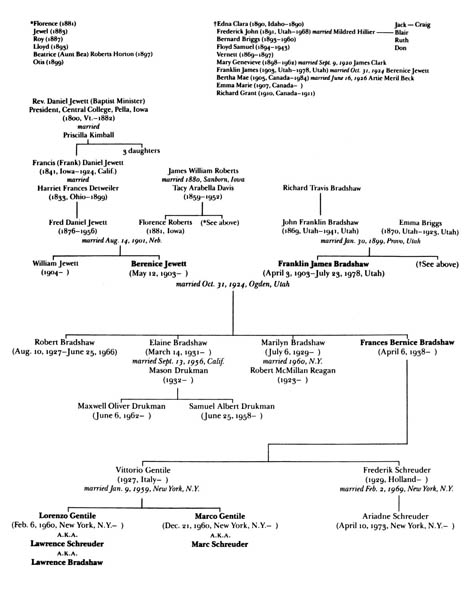

AT SIX FORTY-FIVE Sunday morning, Berenice Bradshaw heard the ancient Ford pickup cough and gargle in the driveway and knew her husband was leaving for work. Mrs. Bradshaw was seventy-five years old, and slightly deaf. She did not actually hear the old man leave his small room just across the hall from her own, or run his tepid bath. She did not hear him do his thirty-one pushups, or stir up his breakfast of oatmeal with evaporated milk, or hack off and brown-bag the chunk of her meat loaf that would become his lunch. But she knew he had done each of these things. The Bradshaws had moved into the bungalow on South Gilmer Drive one April day in 1937, and every single morning since then Franklin Bradshaw had followed precisely the same routine, Saturday and Sunday mornings included: 15,055 tepid baths, 15,055 pots of oatmeal.

Franklin Bradshaw would not return home from the disheveled old Bradshaw Auto Parts warehouse, hard by the Union Pacific railroad tracks, until after nine oclock. Time was when he did not get home from work until ten or eleven or even midnight, but he was seventy-six now, and lacked the energy he once had. By the time he came home she would have eaten supper and be down in her small split-level basement office, pasting snapshots into her photograph albums or working on her genealogy charts. He would warm up his own supper: more meat loaf, which she had prepared for him during the day, and Jell-O with fruit, and perhaps a homemade bran muffin. While he ate, he would read his newspaper. 15,055 copies of the Salt Lake City Tribune.

Weekdays or weekends, year in and year out, the routine never varied. So on this particular Sunday morning, July 23, 1978, when she heard Franklins old blue Courier truck starting up, Berenice Bradshaw did what she had done on so many other identical Sundays: she rolled over and went briefly back to sleep. At 8:30 A.M . Mrs. Bradshaw got up and went down to the basement to awaken her seventeen-year-old grandson Larry, who was spending the summer with his grandparents. She warned him not to be late for his ten-thirty flying lesson out at Skyhawk Aviation, near the Great Salt Lake. Larry was never easy to awaken, and this morning it took longer than usual. Larry had worked at the warehouse with his grandfather the evening before, the only time this summer the boy had set foot down there. The rambunctious Schreuder grandsons, Larry and his brother Marc, were not popular with the other employees. Last year, after the two sixteen-year-olds had spent the summer working at Bradshaws, some employees had threatened to quit. That was why this summer Granny Bradshaw was paying $3,500 for Larry to take flying lessons instead.

A few minutes past ten oclock Mrs. Bradshaws doorbell rang. On her front porch was a police officer accompanied by a Mormon elder and Doug Steele, manager of Bradshaw Auto Parts and her husbands oldest friend. She asked them in and the elder told her to sit down. He knelt down beside her. We hate to do this, Berenice, he said. Weve had a tragic accident. It concerns your husband

I dont understand. She turned to Doug Steele. Whats he trying to say, Doug?

Berenice, Franks been shot. Hes been killed.

Oh, my God! My God!

Now, help us out, Berenice. I know youve got some tranquilizers around here. Where are they? Steele brought the pills and some water and Mrs. Bradshaw calmed down somewhat and the policeman said it looked like a robbery. The cash register was open, Franks wallet and some coins and credit cards were scattered on the floor.

Whatll we do, Doug? Whatll we do?

The grizzled manager put his arm around her heaving shoulders. We have to reach out for the family now, Berenice. Get hold of the girls.

All day long Mrs. Bradshaw, assisted by her grandson, tried to reach her three married daughters, two in New York City and one in Oregon. But this was July and a Sunday. Nobody was at home. It would be past midnight before she spoke to them all.

At 5:45 P.M . Mrs. Bradshaw and Larry went down to the Hall of Justice to give their statements to the police. No gun had been found, they were told, and there were no witnesses, no clues of any kind. The old man had been ambushed, shot in the back. It could have been anyone.

I believe in capital punishment, so help me, Mrs. Bradshaw said. The widow answered all the police officers questions. She told them her daughters names and addresses. She described her husbands work habits, his business, his employees, all very, very fine wonderful men

They asked about her husbands will. She had not yet had time to look for it, she said. Nothing but callers and phones all day. But she thought a copy was somewhere in her basement files. Ive seen it but my family didnt like it, and he didnt like it. And so it is still there, but nobody likes it.