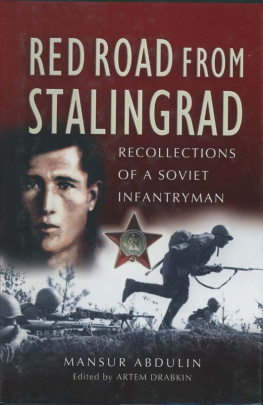

RED ROAD FROM STALINGRAD

RED ROAD FROM

STALINGRAD

Recollections of

a Soviet Infantryman

MANSUR ABDULIN

Editor: Artem Drabkin

Translator: Denis Fedosov

Research Articles: Alexei Isaev

English text: Christopher Summerville

Pen & Sword

MILITARY

First published in Great Britain in 2004 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Mansur Abdulin 2004

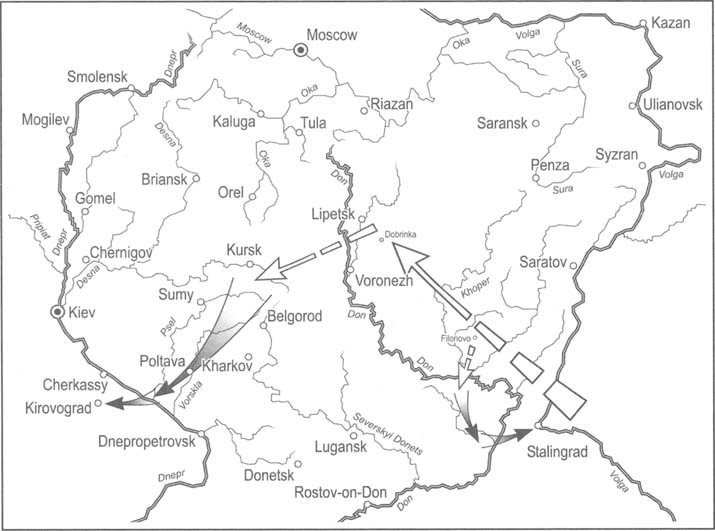

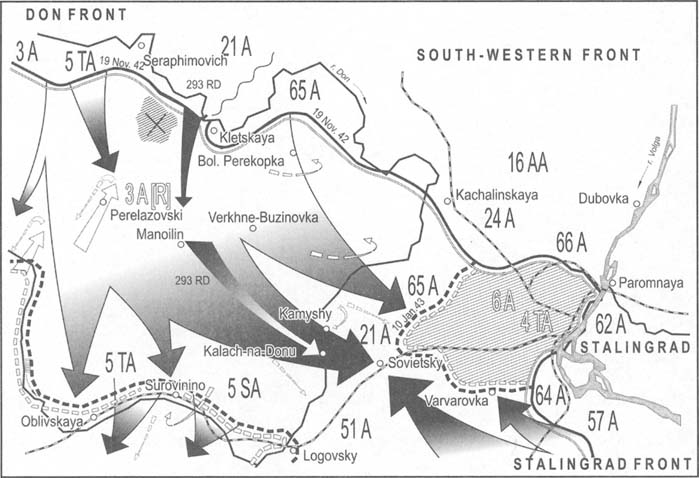

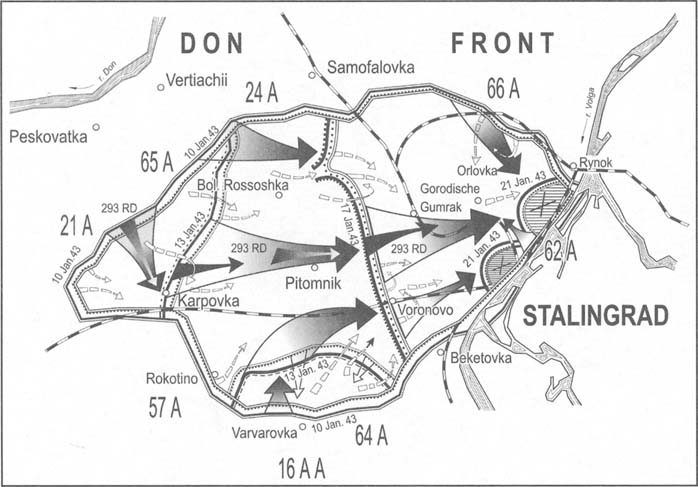

Maps: Max Bohdanowski

Publication made possible by the I Remember website

(www.iremember.ru/index_e.htm) and its director, Artem Drabkin

ISBN 1 84415 145 X

The right of Mansur Abdulin to be identified as Author of this Work has

been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including

photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Sabon by Phoenix Typesetting, Auldgirth, Dumfriesshire

Printed and bound in England by CPI UK.

Pen & Sword Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen

& Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History,

Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

This must never happen again! Such was the slogan proclaimed after the Great Victory, which became an important principle in Soviet domestic and foreign policy. Winning, together with its allies, the bloodiest war in history, the country suffered enormous losses. Almost 27 million people perished (almost 15 per cent of the peacetime population). Millions of my compatriots were killed in action, ended their lives in German concentration camps, starved or froze to death in besieged Leningrad or in evacuation. The scorched earth policy, which both armies pursued during retreat, resulted in the total destruction of the lands which before the war counted a population of 88 million and had produced up to 40 per cent of GDP. Millions of people lost their homes and were forced to live in abominable conditions. The fear that such a catastrophe might repeat itself haunted the nation. It was one of the reasons that the countrys leadership adopted an enormous defense budget, which became a terrible strain for the economy. Because of this very real fear, ordinary people used to store a certain amount of strategic products salt, matches, sugar, canned goods I remember as kid how my grand mother who had lived through the famine of war kept trying all the time to give me something to eat, and was very distressed when I refused! We children, born some thirty years after the war, continued to refight it in our play, in the streets. We divided into groups of our men and Germans and the first German words we learned were Hnde hoch, Nicht schiessen, and Hitler Kaputt. In almost every house one could see some reminder of the war. I still have my fathers decorations and a German case for gas mask filters standing in the corridor of my flat its a good thing to sit on when youre tying your shoelaces!

A desire to forget the horrors of the war as fast as possible, to heal its woundsas well as to conceal the mistakes of the countrys leadership and military chiefsled to a propaganda campaign based on the image of a faceless Soviet soldier, bearing on his shoulders the full weight of the struggle with German fascism, while praising the heroism of the Soviet people. This attitude meant propagating a simplified, strictly official interpretation of what really happened. As a result, those memoirs published in the Soviet era were strongly affected by both external and internal censorship. Only in the late eighties could the full truth about the war come to light.

That was the decade Mansur Abdulins book was published. Last year, when I saw it for the first time, I realized that here I held a true confession of the heroic Soviet people, written by a highly original man. What makes these memoirs absolutely unique is that Abdulin was involved in front line action for a whole year, while statistics tell us that on average, a Red Army infantryman survived the battlefield for only a fortnight, after which he was either killed or wounded. This period of time allowed Mansur to gain a wealth of experience, which he relates in this book. Being a gifted story-teller, Abdulin, in a frank and straightforward way, describes his life in the trenches. He was perfectly aware that the carnage, which he was forced to be a part of, left him practically no chance of survival. His main goal was to sell his life as dearly as possible, which meant killing others, killing as many enemy soldiers as he was able. The war on the Eastern Front was marked by an amazing degree of hatred and violence, connected largely with the German intentions of totally annihilating the USSR and enslaving its population. The Western reader has already had an opportunity to learn of the experiences of the German side, by reading the books of such veterans as Guy Sajer or Gnter K. Koschorrek, while memoirs of Soviet soldiers were almost totally inaccessible. This is why I instantly felt enthusiastic about an English edition.

But how could I find the author? The book was published thirteen years ago and Abdulin must be no less than eighty by now. Was he alive? How could I reach him? It was mentioned in the accompanying text that Mansur Abdulin resides in Novotroitsk, in the Orenburg Region. I called the information office of this small town situated in the Southern Urals. The girl at the other end of the line misspelled the surname at first, and answered that she didnt have such a man on her list. My heart sank! What did you say the name was? Abdulin.

Sorry, I was looking for Abdullin. Just a moment Yes, we have an Abdulin M.G. I immediately phoned Mansur and introduced myself: How would you feel about preparing an English edition of your book? Why not? Lets give it a try

Artem Drabkin,

Moscow 2004

The war, the front, means shooting. Mortars, machine- and submachine guns, artillery. I made my first shot in action on 6 November 1942, on the South-Western Front, from an autoloading SVT rifle. This is how it was