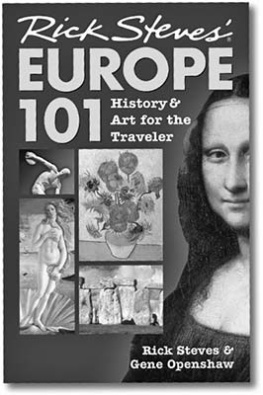

Through the Day,

through the Night

A Flemish Belgian Boyhood

and World War II

Jan Vansina

The University of Wisconsin Press

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 537112059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 2014

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vansina, Jan, author.

Through the day, through the night: a Flemish Belgian boyhood and

World War II / Jan Vansina.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-299-29994-1 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-299-29993-4 (e-book)

1. Vansina, Jan. 2. FlemingsBelgiumBiography.

3. BelgiansBiography. 4. HistoriansUnited StatesBiography.

5. BelgiumHistoryGerman occupation, 19401945 Biography.

I. Title.

DH689.V36A3 2014

949.3042092dc23

[B]

2013033115

Riding, riding, riding, through the day, through the night, through the day.

Riding, riding, riding.

And one's courage has grown so tired, and one's longing so great.

Rainer Maria Rilke, The Lay of the Love and Death of Cornet Christoph Rilke (1906)

Contents

Preface

I love stories, especially stories that really happened. I like to listen to them, I like to tell them, and I have heard a great many more or less true stories about the past as I studied oral history and oral tradition. In the last few years alone, my work has led me to the manuscript record of the oral memoirs of an African prince as well as those of a Dutch trader in the Congo. Each such account unfolds the story of another time, as remembered by an individual who experienced it from a distinctly personal point of view. So it was perhaps inevitable that even a casual suggestion made in a swimming pool would lead me to write this story of my own past in a tumultuous and now-distant time.

Given my professional reflexes, it is also natural that this tale about my boyhood long ago and in a foreign country, addressed mostly to listeners in another age and of a different culture, emphasizes its historical and ethnographic dimensions. I grew up during the most turbulent years of the twentieth century, in Flanders, the northern half of Belgium, a small country in western Europe, and in telling my story I have in mind an audience with no direct experience of the events I describe. In a modest way the story aims therefore to contribute to the ethnography of Flemish culture in those days.

I have also taken great pains to ensure that it fully rests on evidence, so that it becomes itself an oral history backed to some extent by written data. I want to add something to the existing historical literature, namely, an account of those times as seen through the eyes of a child, and especially a boy's experience of World War II. In reconstructing the chronology of the period I have often checked my memory against the relevant documents, be they concerned with momentous events such as the death of a king or the start of a war, or with more private happenings such as births, deaths, school reports, and family matters. Nevertheless, the core of this account stems directly from my own reminiscences. I am fully aware of the fragility of this kind of evidence, and I have been as diligent as I can to crosscheck my own memory against that of my surviving siblings, without asking leading questions. But I also have been fortunate in that three of them, at my prompting but without further suggestions, wrote down substantial accounts of their reminiscences, while three others contributed some memories about specific events. Hopefully the resulting book will provide a new and more concrete dimension to that period and correct at least some of the distortions caused by wartime propaganda that still haunt most popular accounts of the period today. In particular, I would be pleased if readers came to question the pernicious stereotypes that abound in such accounts and, more broadly, to question any statement about any group of people that treats it as if it were a single person with uniform values, motivations, and actions.

Yes, ethnography, history, historiography the story of my growing up may well contain a bit of all of these, but first and foremost it is just a story about growing up, a tale to be enjoyed. May its readers do so.

Is the child really the father of the man, as the well-known adage has it? Many among us believe this to be true, at least to a certain extent, so that when a child grows up and the proverbial man happens to be a scholar, other scholars may well wonder how much that child's experiences influenced the adult scholarship that emerged. I happen to be a case in point, because in the end I turned into a historian of Africa. Hence some former colleagues or students will no doubt search this story for telltale clues about distinctive patterns in my later scholarship. Until now I have written virtually nothing about my boyhood, and even those most familiar with my work do not realize how different the culture of Flanders at the time was from that of the United States now, nor have they any inkling about the impact the turbulence of the times had on me. What, if anything, did my childhood have to do with my later views about the notion of culture, for instance? How about my convictions concerning the importance of language as an expression of culture and a source of history? Did my later notions of tradition and my sensitivity to oral history have any precursors in my younger years? Did youthful experiences prepare me especially for encounters with foreign cultures, and how did I acquire the self-reliance necessary to thrive in unfamiliar surroundings and to adopt the patterns that rural life fieldwork imposes, including its lack of many amenities and commodities, or its relative absence of medical assistance?

Those who know my work well will soon figure out for themselves exactly how my childhood shaped my later personality and scholarship, even though I do not dwell much on such issues anywhere in this story, for I do not want to suggest that I was somehow predestined to spend my adult life as an Africanist. After all, the same tale might just as well have led to a wholly different outcome, and in these early years of my life the world still offered infinite paths I might have taken through innumerable landscapes. Still, at the end of my story, in the epilogue, I do provide a list of clues for those who delight in such sleuthing. Happy hunting!

Acknowledgments

This book would never have been written without the input of Dr. Gwen Walker, acquisition editor for the University of Wisconsin Press. Initially, a remark by a sociologist acquaintance suggested the idea of an autobiography to me and led me to send a vague query to Dr. Walker about the feasibility of such a venture. Once I had told her the whole story orally she strongly encouraged me to forge ahead with it. But this was not the genre of book I was used to, and I rather doubted whether I possessed even the minimum literary skill required to write an autobiography. But as I wrote one sample chapter after another she kept reassuring me and encouraged me to persevere. At first she only made an occasional suggestion for the improvement of the literary presentation of some chapters, but those proved to be essential for the way the narrative developed. Later she graciously offered to edit the whole book herself in spite of her considerable workload, and in doing so she greatly improved it. Faced with so much generosity I can only say: Thank you, Gwen!