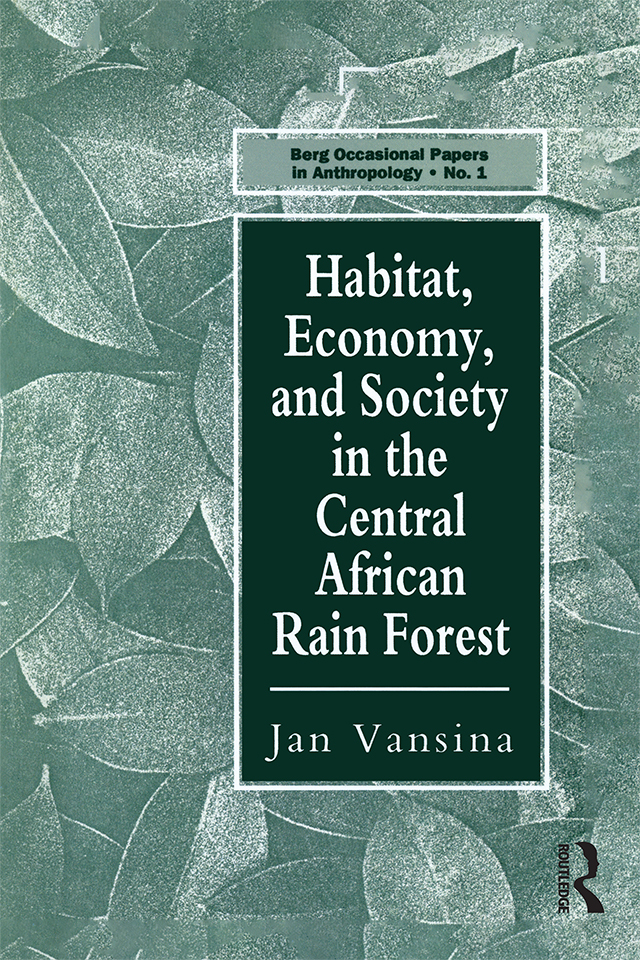

First published 1992 by Berg Publishers

Published 2020 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Anthropology Department, University College, London 1992

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in Publication Data applied for.

ISBN 13: 978-0-8549-6733-9 (pbk)

This lecture series has been created to honor a great scholar who was ahead of his time, Professor Daryll Forde. Opening the series, this paper is intended to pay a special tribute to him and to recognize the intellectual debt that we all, and I in particular, owe to him. Among Forde's many works, perhaps his most influential book has been Habitat, Economy, and Society: A Geographical Introduction to Ethnology (1934). This book is a study of the relationship between physical environment, techniques of production, and social structure. It presents a number of case studies involving food gatherers, cultivators, and pastoral nomads, and then provides a synopsis of the world's dominant techniques of production, their relationship to the economy, and their impact on society. In his conclusions, Forde rejected the three main theories of determinism common among anthropologists of his time: physical determinism, social determinism, and economic determinism. Physical determinism attributed all sociocultural differences to the habitat, and, as Forde observed, flowed from racism. At the opposite extreme, the social determinists, usually functionalists at that time, denied that the habitat had any influence on society. In between, economic determinism, a child of evolutionary theory, attributed such differences to the dominant techniques of food production. Adherents of economic determinism believed that man gradually overcame the constraints of his habitats. Determinists of all stripes could make a case for their respective positions only, as Forde put it, "by selecting an instance here and a generalization there.... The reality of human activity escapes through so coarse a mesh" (460). In Forde's view, a finer understanding of the relationship between habitat, economy, and society required much more. "While the investigation of the relations between different elements and activities within a single culture is essential for the appreciation of its individuality and internal structure, it cannot alone reveal the processes whereby the elements as such have come to exist. Comparative and historical studies are essential for the elucidation of these aspects of culture" (470; see also 471-72).

I am also greatly indebted to Ms. M. Wagner for her frank and incisive editorial comments.

One notes with fascination in this passage and in the whole book that Forde was not swept away by the functionalist tide that was surging in Great Britain at the time (Kuper 1973:57). He was well ahead of his time, as his stress on the then unusual concept of process shows. His views on both the insufficiency of theory and the need for an approach that encompasses historical, comparative, and functionalist study are still valid today, despite the exponential increase in information available about other cultures. R. McC. Netting echoes Forde in the most recent edition of Cultural Ecology (1977:95): "To be convincing our findings require not only correlations leading to logical functional explanations, but also cross-cultural comparisons and evidence of historical change" (85-87).

Today, however, the determinisms denounced by Forde are still rampant. Certainly the language in which they are expressed has been updated, but the essence of the determinist positions has not changed. The development of ecology has fueled a new kind of determinism: environmental determinism. Economic determinism still resonates in the endless debates about modes of production, while social determinists of the political economy or neofunctionalist social determinists still propagate such extreme statements as "All diseases are social" or "People eat to be sociable."

The time has come to test Forde's proposal that comparative and historical research as well as functional studies be conducted. This comparative and historical research can be done for the peoples living in the rain forests of central Africa. The published materials supplemented by archival information are sufficient to conduct comparative research in historical depth for all the peoples in the region. The characteristics of rain-forest habitats are similar enough to ascertain whether those habitats absolutely determine a major aspect of social and cultural life. Comparing this data with similar information gathered on peoples living in other major rain forests of the world should further confirm such a determining feature. But current research has not found any such relationship. The relationship between habitat and society is much more complex than that.

Some findings, however, hold for all societies in this huge area of Africa. These findings will be discussed in turn, from the general to the specific. Surprisingly, one must begin with a discussion of the nature of reality. Then follows a consideration of the nature of rain forests, the proper spatial units to be considered, and the type of interaction involved in these relationships. The focus then shifts to a specific but major relationship: the specific character of production, mainly food production, and the strategies of the inhabitants with regard to it. The topics to be discussed are, in succession: the nature of reality; the nature of rain forests, habitats, and spatial units; the direction of interaction between habitat, economy, and society; food production as a system; and the search for optimal returns.

The Nature of Reality

Forde cited Lucien Fibvre approvingly: "Wherever 'man' and natural products are concerned the 'idea' intervenes" (463), but Forde used the statement only in the context of his discussion of restrictive or limiting versus permissive factors. The quotation did not occur to him when he opened his book with an imaginary description of how a Tasmanian family would interpret a film about Western urban life. He concluded from this description that people know their habitat only through their own interpretation. Reality to them could be only cognitive, not physical.

To me, however, it is evident that there are two types of reality, physical or phenomenological and cognitive, and this dichotomy has important consequences. Both cognitive and physical reality are equally real (even though some philosophers doubt whether physical reality exists at all). The interaction between the two is crucial for an assessment of the relations between habitat, society, and culture. People can act only on the basis of their cognitive reality, not on the basis of physical reality itself; cognitive reality is culture. Therefore, the most intimate of links exist between culture and habitat.