SHORT CUTS

INTRODUCTIONS TO FILM STUDIES

OTHER TITLES IN THE SHORT CUTS SERIES

THE HORROR GENRE: FROM BEELZEBUB TO BLAIR WITCH Paul Wells

THE STAR SYSTEM: HOLLYWOODS PRODUCTION OF POPULAR IDENTITIES Paul McDonald

SCIENCE FICTION CINEMA: FROM OUTERSPACE TO CYBERSPACE Geoff King and Tanya Krzywinska

EARLY SOVIET CINEMA: INNOVATION, IDEOLOGY AND PROPAGANDA David Gillespie

READING HOLLYWOOD: SPACES AND MEANINGS IN AMERICAN FILM Deborah Thomas

DISASTER MOVIES: THE CINEMA OF CATASTROPHE Stephen Keane

THE WESTERN GENRE: FROM LORDSBURG TO BIG WHISKEY John Saunders

PSYCHOANALYSIS AND CINEMA: THE PLAY OF SHADOWS Vicky Lebeau

COSTUME AND CINEMA: DRESS CODES IN POPULAR FILM Sarah Street

MISE-EN-SCNE: FILM STYLE AND INTERPRETATION John Gibbs

NEW CHINESE CINEMA: CHALLENGING REPRESENTATIONS Sheila Cornelius with Ian Haydn Smith

SCENARIO: THE CRAFT OF SCREENWRITING Tudor Gates

ANIMATION: GENRE AND AUTHORSHIP Paul Wells

WOMENS CINEMA: THE CONTESTED SCREEN Alison Butler

BRITISH SOCIAL REALISM: FROM DOCUMENTARY TO BRIT GRIT Samantha Lay

FILM EDITING: THE ART OF THE EXPRESSIVE Valerie Orpen

AVANT-GARDE FILM: FORMS, THEMES AND PASSIONS Michael OPray

PRODUCTION DESIGN: ARCHITECTS OF THE SCREEN Jane Barnwell

NEW GERMAN CINEMA: IMAGES OF A GENERATION Julia Knight

EARLY CINEMA: FROM FACTORY GATE TO DREAM FACTORY Simon Popple and Joe Kember

MUSIC IN FILM: SOUNDTRACKS AND SYNERGY Pauline Reay

FEMINIST FILM STUDIES: WRITING THE WOMAN INTO CINEMA Janet McCabe

MELODRAMA: GENRE STYLE SENSIBILITY John Mercer and Martin Shingler

FILM PERFORMANCE: FROM ACHIEVEMENT TO APPRECITATION Andrew Klevan

NEW DIGITAL CINEMA: REINVENTING THE MOVING IMAGE Holly Willis

THE MUSICAL: RACE, GENDER AND PERFORMANCE Susan Smith

FILM NOIR: FROM BERLIN TO SIN CITY Mark Bould

TEEN MOVIES: AMERICAN YOUTH ON SCREEN Tim Shary

DOCUMENTARY: THE MARGINS OF REALITY Paul Ward

THE NEW HOLLYWOOD

FROM BONNIE AND CLYDE TO STAR WARS

PETER KRMER

A Wallflower Press Book

Published by

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright Peter Krmer 2005

All rights reserved.

E-ISBN 978-0-231-85005-6

Wallflower Press is a registered trademark of Columbia University Press.

A complete CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-1-904764-58-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-85005-6 (e-book)

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover image: THE GRADUATE (1967), Embassy Brothers Corporation Book and cover design by rob Bowden design

CONTENTS

Thanks to Joseph Garncarz, whose exemplary work on German cinema has provided me with a model for the integrated analysis of hit patterns, film industrial developments, shifts in public opinion and generational change. Also thanks to Martin Barker, Mark Jancovich and Jim Russell, who together with Joseph provided extensive comments on the manuscript. As always, Sheldon Hall was an invaluable source of information.

Research for this project in American archives was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Board.

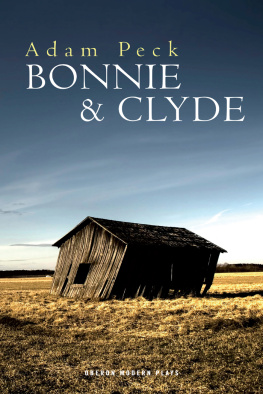

FIGURE 1 Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967)

On 8 December 1967, Time magazines cover announced The New Cinema: Violence Sex Art with a picture from Bonnie and Clyde, a violent, funny and lyrical film about two Depression-era bank robbers; inside, an article entitled The Shock of Freedom in Films declared Bonnie and Clyde to be a watershed picture, the kind that signals a new style, a new trend (Kanfer 1971: 331; see also Biskind 1998: 45). The article argued that by building on formal and thematic innovations both in American cinema and, more importantly, in European cinema, and by combining commercial success with critical controversy, Bonnie and Clyde demonstrated that Hollywood was undergoing a renaissance, a period of great artistic achievement based on new freedom and widespread experimentation (1971: 333). The film provoked a battle among movie critics, with Bosley Crowther, a veteran of the New York Times, condemning the film, and younger writers like Pauline Kael celebrating it (in the New Yorker) (1971: 330). Some critics even battled themselves: Newsweek panned the film, but the following week returned to praise it (ibid.). According to Time, the appearance of films like Bonnie and Clyde was made possible by the major studios unprecedented willingness to open doors and checkbooks to innovation-minded producers and directors, many of them unusually young, including 28-year-old Francis Ford Coppola, a precocious graduate of the nudie industry (1971: 3312). While the magazine was hopeful about the future outcomes of Hollywoods new approach, it also sounded a note of caution: For every bold, experimental foray there are bound to be many ambitious failures or cold, calculated imitations (1971: 333).

Within a few years of the publication of this article, film scholars began to discuss the second half of the 1960s as a period of fundamental change in American film history, tracing the development of the Hollywood renaissance into the 1970s, and variously re-labelling it as modern/modernist American cinema or, more commonly, New Hollywood (see Krmer 1998a; for continuing use of the renaissance label see Jacobs 1977 and Man 1994). In the rapidly expanding literature, three critical agreements soon emerged. Firstly, the late 1960s and early 1970s were a golden age in Hollywood history, characterised by a large number of challenging films. Secondly, most of the outstanding films of these years were the work of a small group of young directors, many of them film school graduates like Francis Ford Coppola who had studied at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) before working in exploitation filmmaking. Thirdly, the period of intense formal and thematic innovation which began around 1967 ended in the mid- to late 1970s, with Jaws (Steven Spielberg, 1975) or, more often, Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977) being selected as markers of another historical turning point.

Confusingly, the term New Hollywood has been applied both to identify a select group of films made from 1967 to the mid-1970s and to refer to this period as a whole. Even more confusingly, the period since the mid- 1970s is also frequently called New Hollywood. To avoid such confusion, I only use the term to refer to the period 196776 in American film history (that is all American films, the film industry and the wider film culture during these years).

While publications about the New Hollywood and its key films and directors have appeared at an impressive rate since the 1970s, from the late 1990s onwards there has been an explosion of interest. In 1998, Peter Biskinds Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock n Roll Generation Saved Hollywood demonstrated that there was a large audience for an in-depth account of the lives and films of some of the key Hollywood personalities of the late 1960s and 1970s (in 2003 a documentary with the same title was released). In 2000 and 2001, volumes on the 1960s and 1970s were published in Scribners authoritative History of the American Cinema series, providing future scholars with an important reference point (Cook 2000, Monaco 2001). The year 2000 saw the publication of the third edition of Robert Kolkers by then classic study of key Hollywood directors since the 1960s entitled