AMAZING GIRLS OF ARIZONA

A TWODOT BOOK

Copyright 2008 Morris Book Publishing, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or by the publisher. Requests for permission should be made in writing to The Globe Pequot Press, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, Connecticut 06437.

TwoDot is a registered trademark of Morris Book Publishing, LLC.

Text design: Debbie V. Nicolais

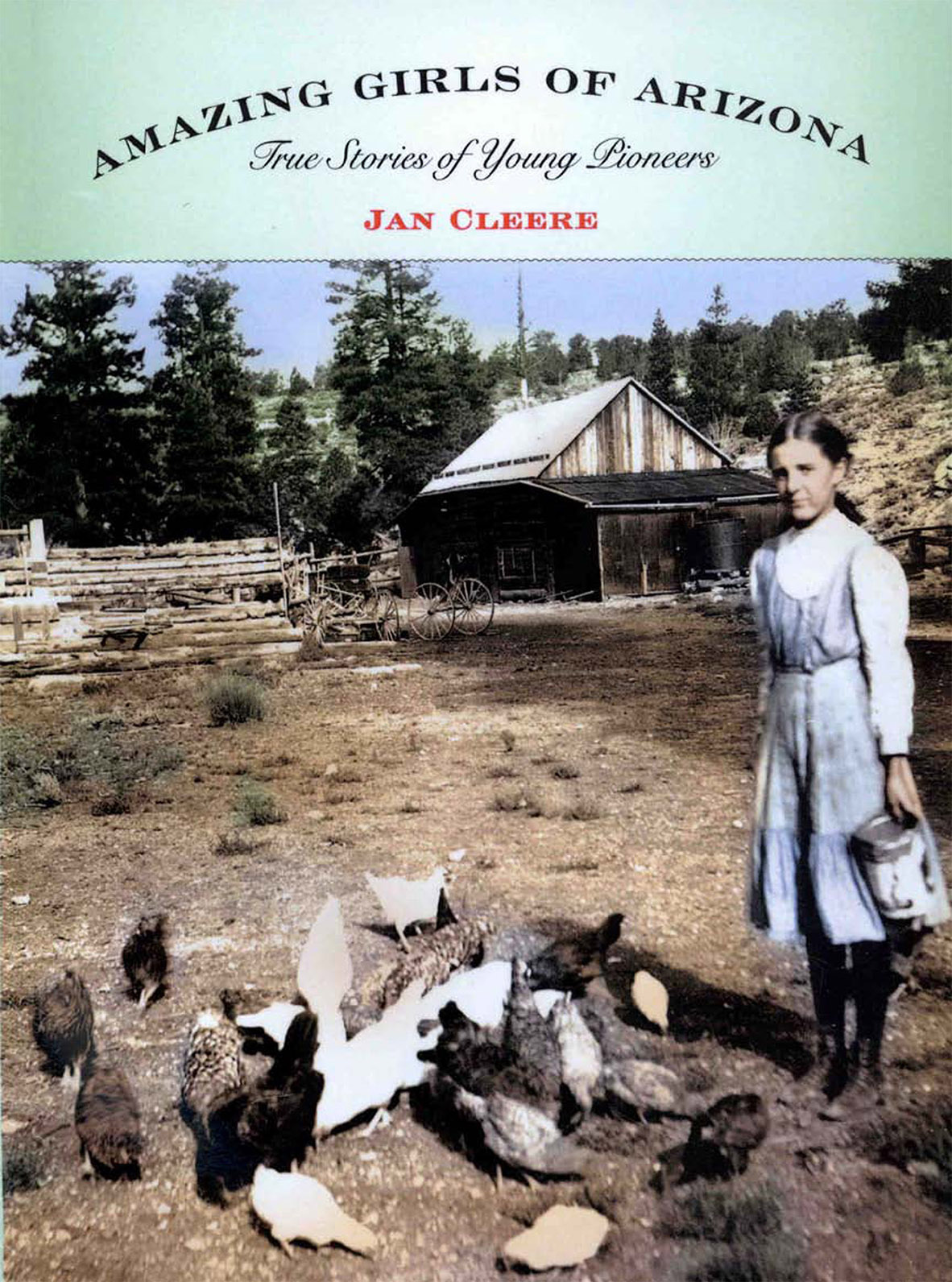

Front cover photo: Edith Jane Bass feeding the chickens, 1910. Image courtesy of Cline Library, Northern Arizona University.

Credits for the photographs that appear with each chapter can be found on page 185.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-7627-4135-9

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Edition/First Printing

To my daughter Sue,

an amazing girl, a remarkable woman.

INTRODUCTION

Children are our most valuable resource, according to the thirty-first President of the United States, Herbert Clark Hoover (19291933). Nowhere was this adage truer than along westward trails and in rustic homes first established by pioneering families. Children were necessary workers who helped with the many chores associated with maintaining a covered wagon on the long trek across the Plains, or the duties and responsibilities of running a ranch or farm in the growing Southwest.

Girls from a very early age were expected to care for younger children, wash clothes and dishes, cook and clean, feed the poultry and pigs, milk the cows, administer to sick animals, and tend the gardens. They helped mend fences, round up wandering herds, and repair dried-up water holes. According to Cathy Luchetti, author of Children of the West: Family Life on the Frontier, Girls were slated to tend the familial home first, their own futures second, and according to their responsibilities, their behavior was closely monitored.

Yet even as early as the 1800s, girls strained against the confines of housework and home chores, particularly those who came west with their families and saw the possibilities and potential of conquering new lands and new beginnings.

They tossed off their restrictive sunbonnets that allowed limited vision, and rode pell-mell across the vast countryside. They watched the sun rise and set as they stoked the campfire on a cattle drive. They learned to wrangle a calf and break a horse, and reveled in the beauty of the desert as they rode out to repair fences, farm the land, and tend the stock. They discovered and embraced the new world that lay before them.

A number of their feats were truly amazing, even astounding. Not just because they were little girls, but also because they met head-on lifes most demanding and difficult experiences.

Early Arizona girls faced unique challenges unbelievable heat, lack of water, strange foods, dangerous animals, and uprooted Native Indians. They learned to cope with the heat, preserve precious water, savor new victuals, avoid and defend themselves from lurking predators. But most of all, they conquered the dangers and difficulties encountered in their daily lives.

The beauty of the Arizona desert, its lush high-mesa plains and snowcapped northern mountains, brought out creative possibilities in young girls as they painted and wrote of the spell the wild territory cast over their lives.

Girls penned letters, journals, and diaries, describing their tears of hardships and heartaches, their dreams of greatness and love. They spoke of Indian massacres and captivity, imprisonment and banishment. They complained about endless chores and squabbling younger siblings. And they boasted of unrewarded accomplishments and prohibited misdeeds. The passage of time has not dimmed their ordeals and achievements. Interspersed with historic details, the earnest stories of these sometimes brave, often heroic young girls have survived the passage of time to be told and retold, with their own words.

INDIAN CAPTIVE

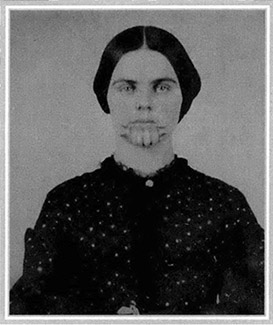

Olive Ann Oatman (Fairchild)

18371903

With each barefoot step, Olive Ann Oatman felt the stab of an Indians lance provoking her to move faster. Tightly clutching her little sisters hand, she tried to quiet the childs sobs of fright and pain as the Indians hurried the two girls across the rock-strewn desert. Mary Anns tiny footsteps left a bloody path as both girls struggled to maintain the unrelenting pace their captors demanded. Farther and farther they traveled, miles from where their abductors had brutally attacked the Oatman family. From the horrors Olive and Mary Ann witnessed, they feared their entire family now lay dead or dying.

Thirteen-year-old Olive did not know what fate awaited her and eight-year-old Mary Ann, but during the ensuing terrifying days, she found herself wishing she might also end up lying beside their parents and five siblings along the banks of the Gila River, deep within Arizona Territory.

Olive had been excited about the adventure that lay before her family as she helped her mother prepare for the long journey from Illinois to the promised land of Bashan that James Colin Brewster, who had broken from Brigham Youngs Mormon teachings, touted as the land of golden opportunity. In 1846, Young had called his people to follow him to Utah. In 1849, Brewster ordered his followers to prepare for the journey to what he described as the real Zion located at the confluence of the Gila and Colorado Rivers, across the desolate and dangerous Southwestern desert. In the summer of 1850, with his farm failing to provide for his growing family, Roys Oatman, Olives father, led his wife Mary Ann and their seven children across the Mississippi River to join other Brewsterites in Independence, Missouri. From there, the wagon train headed west.

The trip was long and arduous, but the travelers remained a cohesive group until October when their wagons rumbled into New Mexico Territory. By then, dissension was brewing among the homesteaders.

Unable to resolve their differences, one group led by Brewster headed toward Santa Fe while the Oatmans hitched their wagons to the contingent going by way of the Rio Grande Valley. Awed by the stark beauty of the surrounding desert, Olive was also old enough to understand the dangers she and her family might encounter along this unfamiliar path. A lack of food already made the travelers disgruntled and tense. Now they faced the possibility of Indian attacks as they crossed into hostile Apache territory.

On January 8, 1851, the Oatmans and the rest of the party arrived in the dusty Mexican town of Tucson. It would take an act of Congress in 1854 to ratify the Gadsden Purchase and make Tucson, along with land south of the Gila River, part of the United States. Even then, this region remained part of New Mexico Territory until 1863 when the Territory of Arizona was finally established.