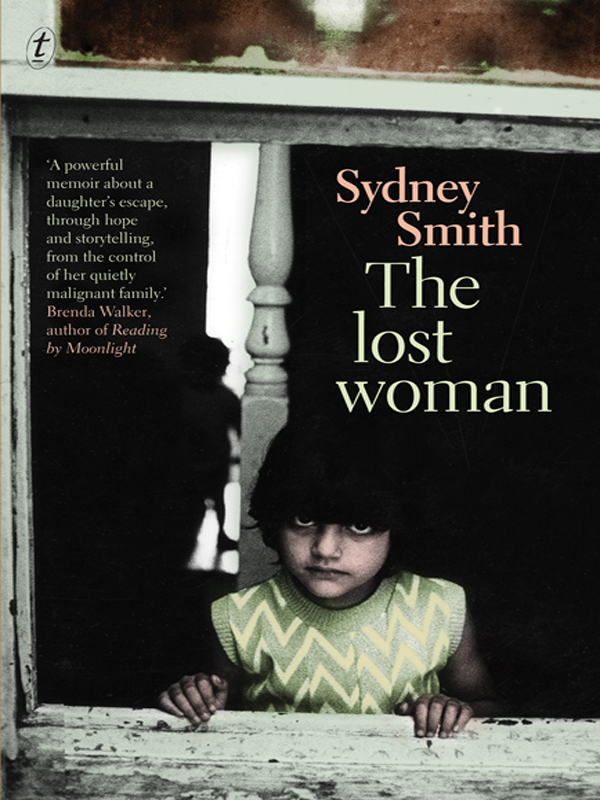

FIONA McGREGOR ON

THE LOST WOMAN

Difficult stories frequently rely on redemptive exits to make them palatable. We are persuaded we cant cope with the raw human capacity for cruelty and horror. But what if the truth is that there is no redemption, except just one more step forward, into the dark. Another breath, just to keep living. And what if the cruelty and horror are wreaked within that hallowed institution, the family, by the person we least suspectthe mother. How can we listen to stories like these?

Sydney Smiths memoir is the gruelling account of a daughter, and to a lesser extent her three brothers, controlled, debased and psychologically tortured to within an inch of her sanity, and life. It is honest, lucid and atmospheric in style, compassionate and even funny in its portraitureand that is why it will make you listen. Smiths seemingly bizarre world could conceivably be hidden behind any door in banal suburbia.

Be as brave as Smith, take this story on. If it surprises you how much damage we can wreak in the domestic sphere, it may surprise you even more how far we can come in our return from that.

Sydney Smith grew up in Wellington, the daughter of a Maori mother and a pakeha father. She is a former winner of the Age Short Story Competition, and her writing has been published in the Age, Imago, New England Review and Island, and in Griffith REVIEW, where accounts of her childhood first appeared. Sydney lives in Melbourne, and is the founder and co-ordinator of the Victorian Mentoring Service for Writers.

textpublishing.com.au

The Text Publishing Company Swann House 22 William Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Australia

Copyright Sydney Smith, 2012

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published in 2012 by The Text Publishing Company

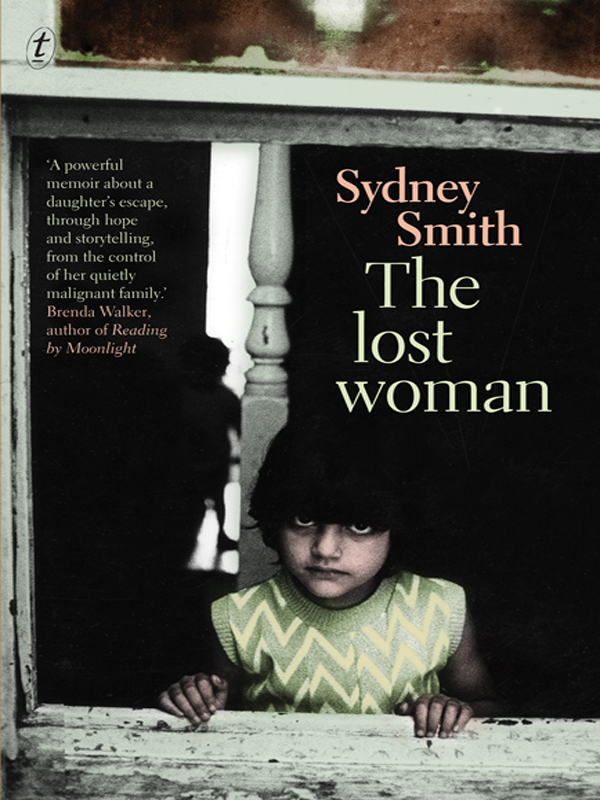

Cover design by WH Chong

Text design by WH Chong and Imogen Stubbs

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press, an Accredited ISO AS/NZS

14001:2004 Environmental Management System printer

Primary print ISBN: 9781921922480 Ebook ISBN: 9781921921384

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Author: Smith, Sydney, 1957

Title: The lost woman / Sydney Smith.

ISBN: 9781921922480 (pbk.)

Subjects: Smith, Sydney, 1957-. Sexual abuse victimsBiography. Incest.

Child abuse. Child sexual abuse. Mothers and daughtersBiography.

Dewey Number: 362.76092

CHAPTER 1

The Vision

I had a vision when I was nine years old. It wasnt a mystical revelation; it wasnt accompanied by stigmata and didnt bring me closer to ideal goodness. But this vision helped me through the years of taking care of Mother.

We were living in a mud-brown weatherboard in Newtown, a suburb of Wellington. It was a gloomy house that stood on the hill of Constable Street, situated in such a way that the sun couldnt get in. On one side we were overshadowed by our neighbours tall fence, made taller by the steep slope of the hill. On the other was a blind wall. At our back were two shops, fused like Siamese twins, that looked onto Constable Street. At our front was a deep yard occupied by a swarming garrison of weeds. The rooms were dark in winter, dark enough to need the light on, and in summer, in the afternoon, a dim glow reflected off our neighbours fence into my parents bedroom and the sitting room.

In my mind, the walls of this house were like the walls of a castle. I looked through the kitchen window at the yard, and sometimes that oblong of overgrown grass seemed as far away as the wider world. I had to stay inside most of the time, when I wasnt at school. Mother wanted me with her. I sat on the floor, reading books I had borrowed from the library at the end of our street, while she prepared meals, baked cakes, ironed my fathers shirts and thought her private, absorbing thoughts.

I wasnt allowed to play outside unless Mother gave me permission. I had to wait for this permission. I must never ask for itasking meant I couldnt have it. My brothers could go out whenever they felt like it, even Brian, who was two years younger than I was. But that life of freedom was not for me. I must stay with Mother.

And yet it often seemed that Mother wasnt there. She was there in the flesha fat woman in a short brown dress flecked with coloured rain, a purple star of veins on the back of one calf, wavy black hair, cats eye glasses perched on her shapeless nose. These glasses often slid down while she was kneading scone dough or doing something else that kept both hands busy. When this happened, she hitched them up by lifting her left cheek, an action that caused her to wink. Since she wasnt looking at anyone when she did this, it seemed she was winking at herself.

But while she was enormously present in her fat, rolling flesh, she was absent in other ways, taken possession of by a dream that filled her mind for days at a time, that held her face immobile in a pose of passionate preoccupation.

I felt invisible when she had that fixed look on her face. I didnt exist. But if I got up to go somewhere elseto my bedroom to get another book, to the toilet, to sit in another room away from hershe said, Where are you going? I could visit the toilet, I could fetch another book, but I couldnt sit by myself in another room, not when she wanted me with her.

I sat on the floor again, opened my book of fairytales and looked up to see what her face was like now. It had settled back into fixed preoccupation. Once again I felt I didnt exist, not in the way my brothers and father seemed to exist. At the same time I was imprisoned, because I couldnt do as I wanted to. I had to sit where she put me and stay there. Nor was I allowed to make a sound, not even when I turned the page.

I thought about Mother a lot, and knew she thought of me rarely, if at all. Her thoughts belonged to that dream.

There was one time each day when I could do as I liked. This was when I walked home from school. It took about fifteen minutes. I liked to stretch it out as long as I could without angering Mother by coming in too late.

The most legitimate way of stretching it out was by visiting the library. It was filled with light and fragrant with floor polish. Right inside the door stood a sign on a chrome stalk that said, Please be quiet. I wanted to obey that rule. I was afraid of punishment if I did not. But obeying it was impossible. How could I obey when the polished parquet floor squeaked every time I took a step? I walked as cautiously as I could, setting each foot down as delicately as I was able to; I tiptoed; I slunk. It made no difference: the waxed floor screamed its alarm. The blue-smocked ladies behind the counter didnt turn a hair at the fearful racket I made.

I squeaked over to the childrens section, an island of movable steel shelves, made my selection and applied myself to the next problem. In front of the bookshelves was a long table with chairs. These chairs were heavy. It took all my strength to move them. It suited me best when one was turned away from the table at an angle, left that way by a previous reader. This was a rare opportunity, the blue-smocked ladies being in the habit of coming by every now and then to set the chairs straight and return discarded books to the shelves. Sometimes, no matter how I tried, I couldnt move a chair; it seemed glued to the parquetry. I usually ended up on the floor with my selections, though I didnt like it because people trod on me.