To my parents, with gratitude.

This one is for you.

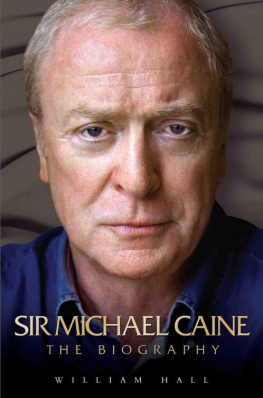

I first met William Hall when he made the long trek out to the Drakensberg Mountains in South Africa to cover the film Zulu for his paper.

That film was my big break, and you dont forget the people who noticed you in the early days.

Since then he has been out on almost every one of my pictures, from Majorca to Marrakesh, Hollywood to the Philippines.

I can think of no one better suited to write this book.

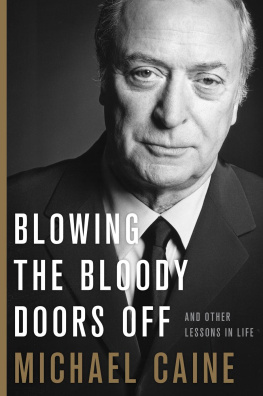

M ichael Caine is in the prime of his life at an age when most respectable actors are settling for cameo roles or walk-ons. He can look back with satisfaction at over three-score-years-and-ten of an amazing career and countless personal achievements to match it.

With more than one hundred movies under his belt in a rollercoaster ride through the good, the bad and the ugly well, did you see The Hand or The Swarm? he might be forgiven for slowing down and casting an eye on the 21 acres of land he is cultivating around his Surrey mansion rather than marching out to face a camera yet again.

Not a bit of it.

The Cockney theatrical knight who became a cinema icon is working as hard as he has ever done, with more scripts than ever dropping through his door. There was Batman Begins, as the butler Alfred, and Shiner, with his role as a seedy boxing promoter. And Last Orders of course, drinking himself to death with his old mates Bob Hoskins, Tom Courtenay and David Hemmings in attendance as barfly cronies.

There was also Austin Powers in Goldmember, alongside Mike Myers and Beyonc Knowles, the kind of film that causes critics to shudder yet makes deafening sounds at the box-office, where it counts. And Its a Very Merry Muppet Christmas Movie, with a title that says it all.

Most important of all, there was The Quiet American. This would be the film that restored our faith in Caine as someone who, given the right script and the right director (in this case Phillip Noyce), could deliver a performance as consummate and compassionate as anything we had seen before. His role as the cynical Times correspondent in Graham Greenes prophetic 1952 vision of Vietnam was acclaimed by both critics and his fellow actors, who deemed it a front runner to net him the Academy Award for best actor that had eluded him all his career.

It was another high point in a life and career that has seen more than its share of peaks and troughs. At 67, Caine was able to state, accurately, I was 30 years a loser, 37 years a winner. Today the odds have moved from even to even better. He has been recognised by his peers in the acting profession with some prized baubles: a Golden Globe, a BAFTA Fellowship, lifetime achievements including the American Film Institute in November 2002, and a whole new army of young fans after being championed by lads magazines and a fresh generation of actors.

Busy? His acting workshops are top of the schedules for drama schools, particularly in America, and have been turned into videos as well as being seen on TV across the world. The movies which made him famous are being remade, with top names and sometimes Michael himself taking a part. Jude Law as Alfie, this time with a New York setting. Mark Wahlberg in The Italian Job, Caine himself reprising one of his best films, Sleuth only this time daring to take on the older mans role played by Laurence Olivier in the complex thriller that in 1972 earned them both Oscar nominations for best actor.

So hes taking chances. But then, Caine always did and today he can afford to. When Michael grew up, the sound of Bow Bells was reaching into the gloomiest recesses of the mean streets where he started life in poverty amid the Great Depression. Today he can afford to smile too, even if he is still prone to sound off occasionally against the class system, his resentment against the British film industry that he claims left him out in the cold, and generally cause a predictable public furore as a result. Over the years that I have been following him around the world on film locations, I have watched that smile broaden into a triumphant grin as he relishes the hard-won fruits of success.

Charting the rise and rise of Michael Caine has been an illuminating experience. From the nervous, introvert young actor tackling his chance of a lifetime in Zulu, he has crystallised into a star of supreme confidence and authority. If any man deserves his success, evolving from the 2 14s 11p he took home in his first pay packet to the millionaire lifestyle he now enjoys, I reckon it is Sir Michael Caine.

And an Oscar for best actor, the one his millions of fans wanted most of all to see bestowed on him? Wouldnt that be the icing on the cake?

William Hall

Highgate Village, London 2007

Z ululand, sunset. July 1963.

He stood alone at one end of the primitive timbered bar, drinking quietly by himself from a half-pint beer tankard. Tall and slim with fair hair curling around his collar, he seemed remote, reflective, somehow detached from the noise and activity in the rest of the room.

He wore the bright red uniform of a lieutenant of the South Wales Borderers, grimy with mud, stained with sweat, but still he looked almost supercilious in it as if he had stepped off the playing fields of Eton rather than the battlefield of Rorkes Drift which they had been re-enacting all day for the mammoth motion picture Zulu.

And he wore glasses with almost aggressively thick steel rims.

No one talked to him.

Outside, a street of native kraal huts, squatting like round hairy coconuts in the brown dust, straggled away towards the river. The sun, a single bloodshot eye, was dipping over the purple plain where the shadows were turning twilight into dust, painting the tall tinder-dry grass dull crimson. In the distance the snow-capped Drakensberg Mountains rose like an impassable barrier to isolate us from the rest of the world.

A stillness settled upon the land. The dusk grew deeper, plunging swiftly towards the African night. Lamps started to flicker and flare along the artificial street of hardboard and straw.

This homemade village, a realistic faade, was the set constructed for the mighty epic they had been struggling to complete now for twelve weeks against the bitter July winter.

The bar itself was no more than a ramshackle hut, rigged up as a temporary saloon for the eighty-strong British crew by art director Ernest Archer and his team with their typical aptitude for producing the miraculous out of the mundane. Some joker had inscribed a crude sign in black paint on the bare door frame: Ties Must be Worn.

The interior was lit by a solitary naked bulb swinging on a cord from the corrugated-iron ceiling. Shadows flickered and danced on the walls like some tribal ritual.

When the unit moved back to civilization that bar would be dismantled and disappear as quickly as it had been built. So would the entire village erected for the cast, technicians and 4,000 Zulus brought in as extras from their bush homes for the costly saga of blood, guts and heroism in the African veldt.

A score of small-part actors in dirt-encrusted uniforms stood around talking loudly, downing beer by the bucketful. Adrenalin released. Banishing the dust and the tension that had clogged their throats all day in the climactic battle scenes that were to become part of cinema history. In one corner, the star and producer Stanley Baker conferred with his director, Cy Endfield, working out the battle lines for the next day.