Sandra Clayton

DOLPHINS

under

my bed

Published by Adlard Coles Nautical

an imprint of A & C Black Publishers Ltd

36 Soho Square, London W1D 3QY

www.adlardcoles.com

Copyright Sandra Clayton 2011

First published by Adlard Coles Nautical in 2011

Print ISBN 978-1-40813-288-3

Ebook ISBN 978-1-40815-523-3

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems without the prior permission in writing of the publishers.

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Note: while all reasonable care has been taken in the publication of this book, the publisher takes no responsibility for the use of the methods or products described in the book

Contents

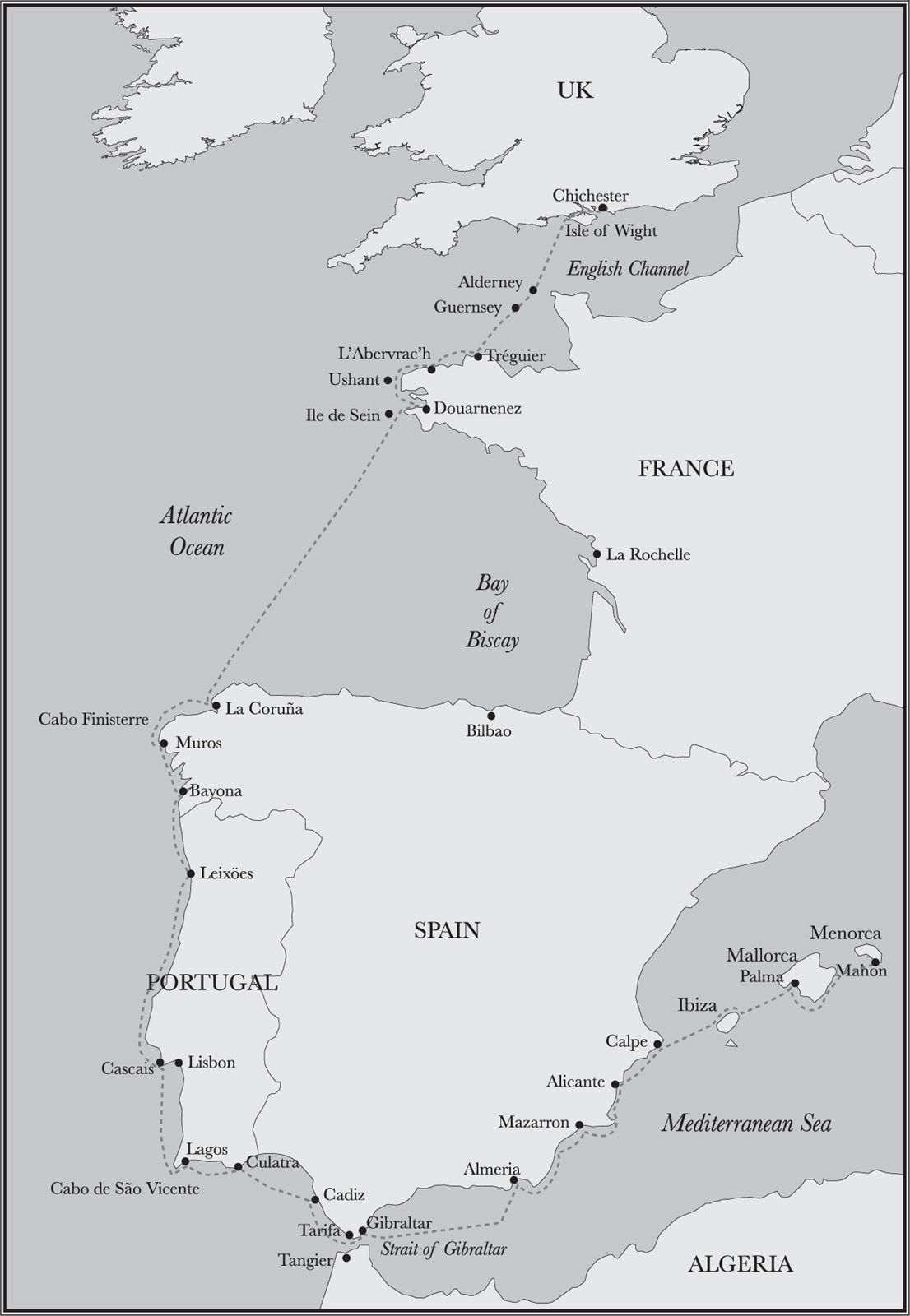

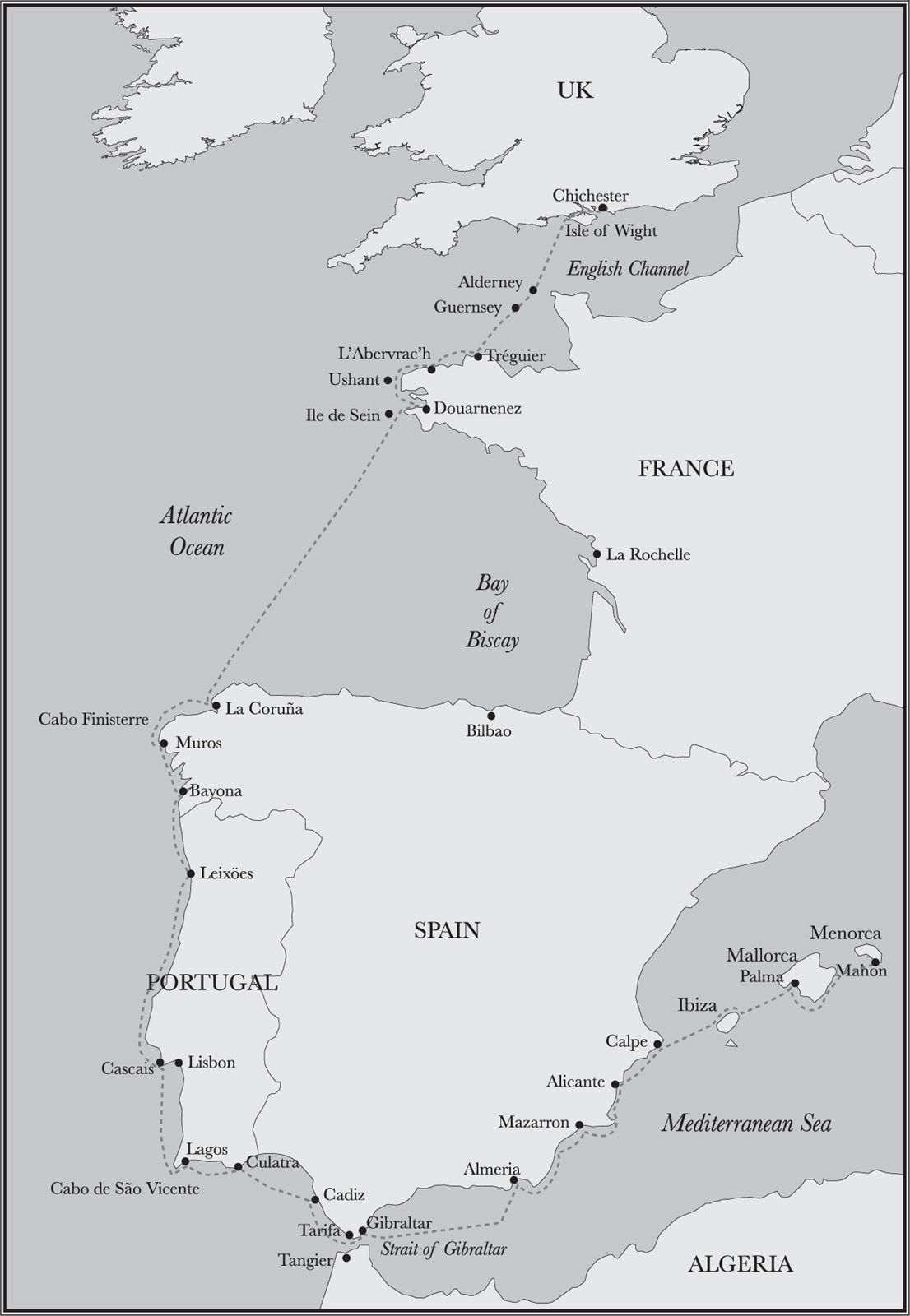

The Journey

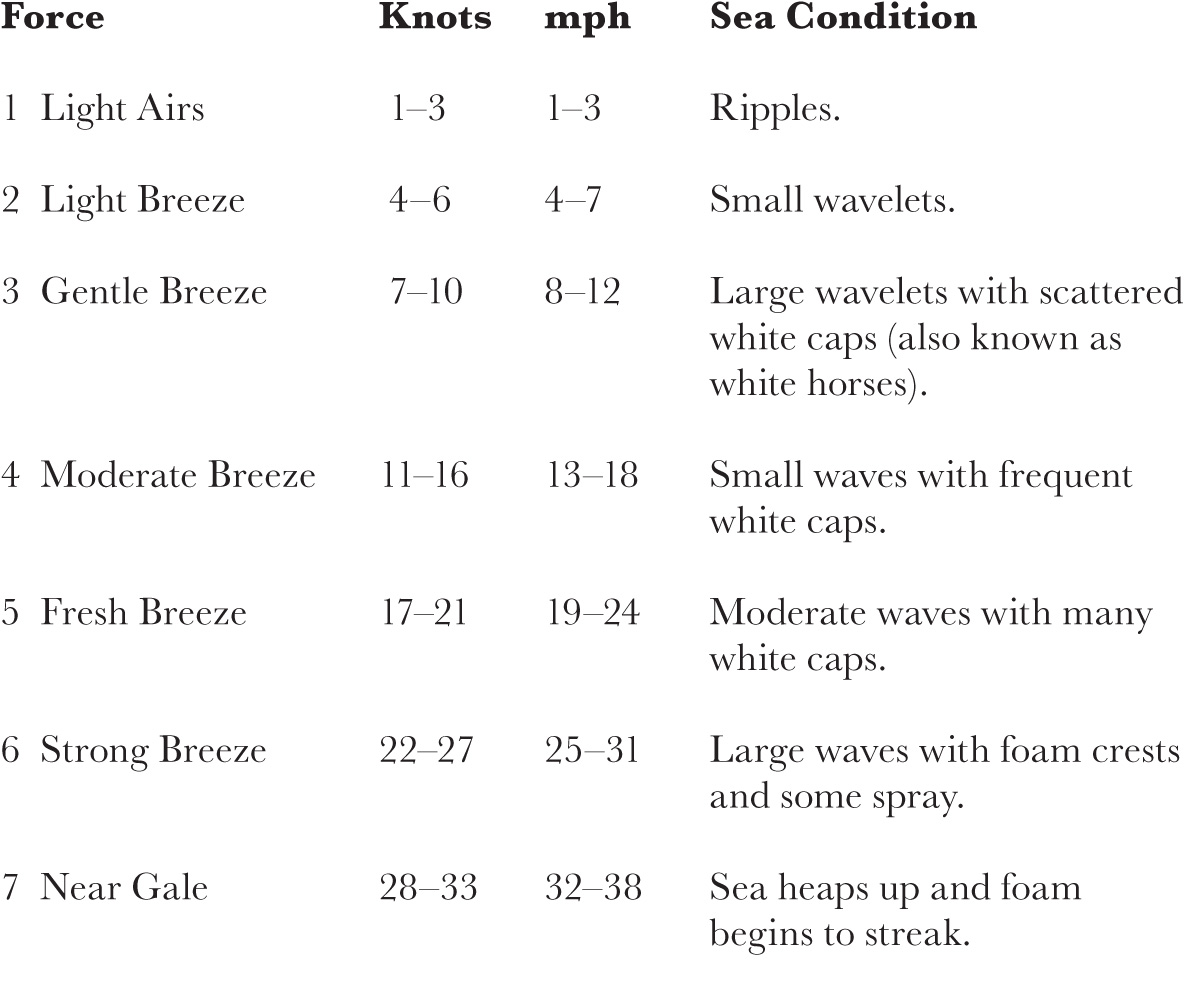

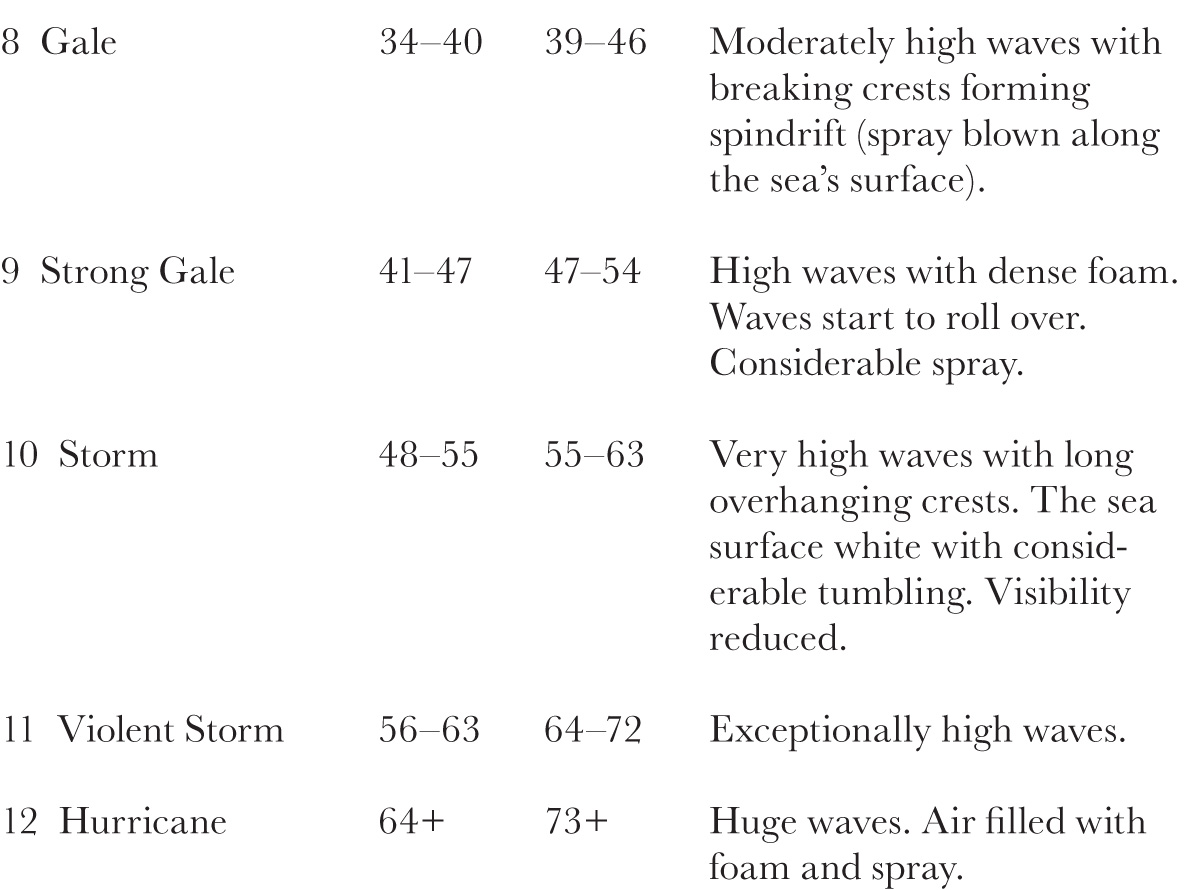

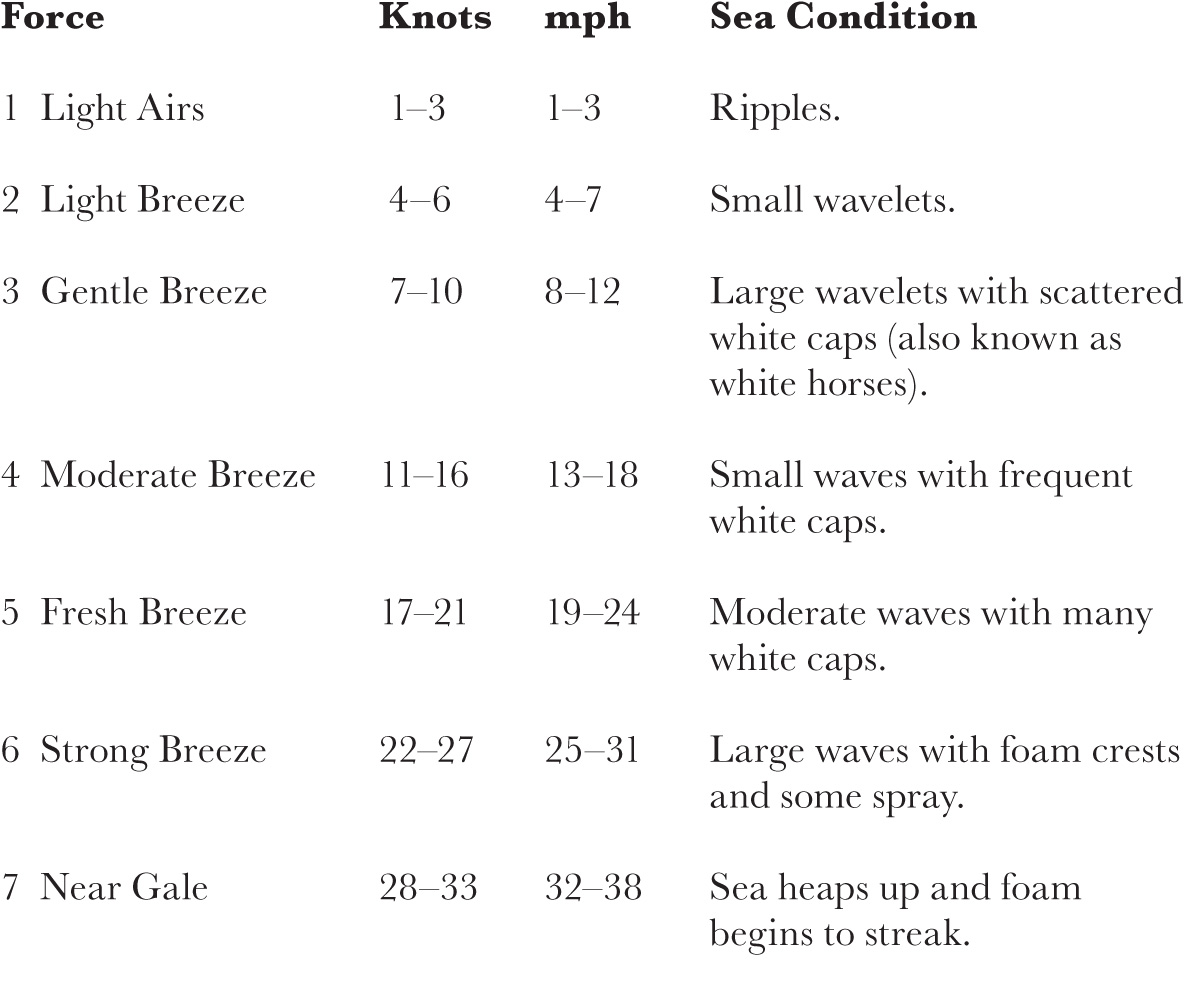

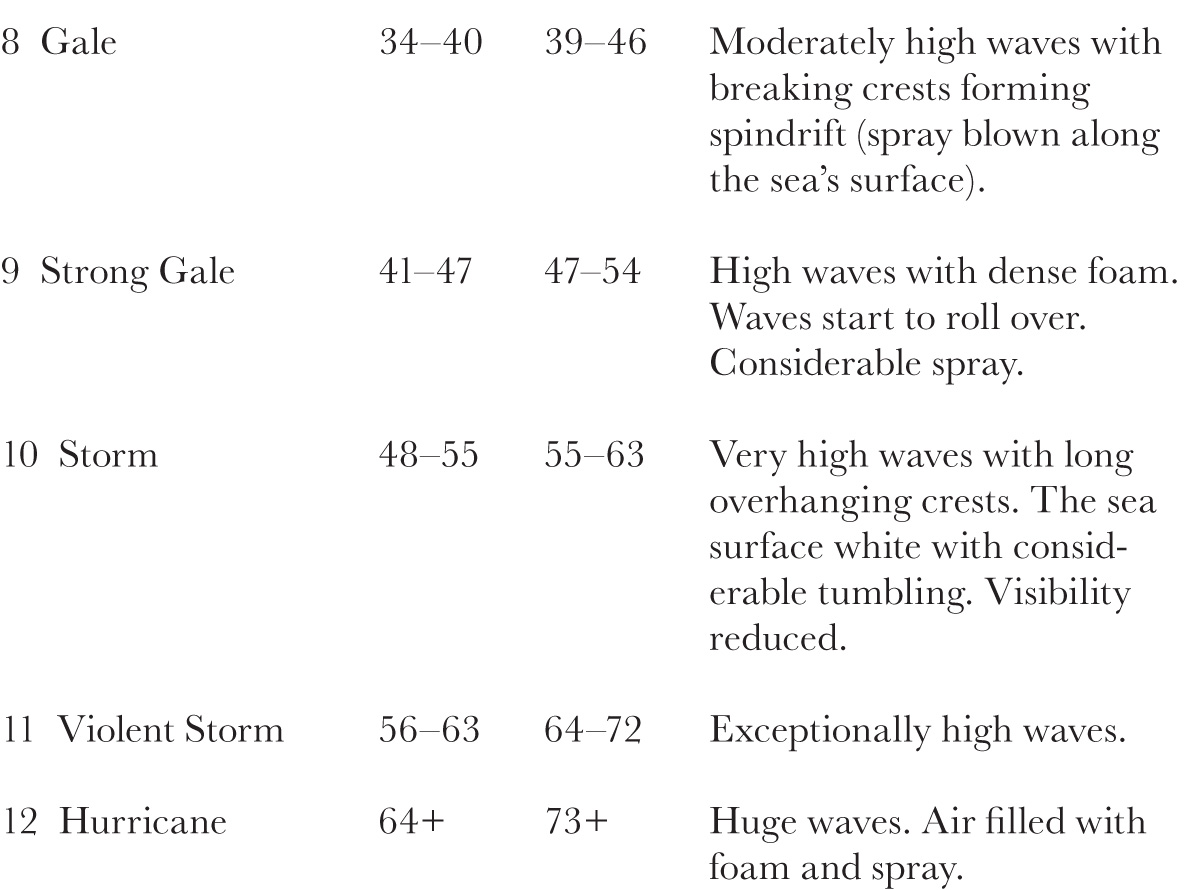

The Beaufort Wind Force Scale

In Britain and much of Europe, wind and vessel speeds are described in knots. One knot equals a nautical mile covered in one hour, and is roughly equivalent to 1.15mph.

Also used is the Beaufort Wind Force Scale. This was created in 1805 by Sir Francis Beaufort, a British naval officer and hydrographer, before instruments were available and has since been adapted for non-naval use. When accurate wind measuring instruments became available it was decided to retain the scale and this accounts for the idiosyncratic speeds, eg Force 5 is 1721 knots, not 1520 as one might expect. Under numbered headings representing wind force, this scale also provides the sea conditions typically associated with them, although these can be affected by the direction from which the wind is coming.

The scale is reproduced on the opposite page.

All travellers, but especially sailors, owe a huge debt to those who have gone before and have subsequently published accurate charts and guides, as well as organisations which provide continuing support. Among the sources that Voyagers crew would like to express gratitude for are:

Admiralty Charts

BBC Shipping Forecast

Cruising Association

Imray Cruising Guides and Charts

Meteorological Office

Reeds Nautical Almanac

Sail & Power Nautical Almanac

Royal National Lifeboat Institution

Royal Yachting Association

UK Coastguard

The author also thanks the following for permission to reproduce copyright material:

British Broadcasting Corporation, Radio 4, London

Richard Evelyn Byrd, Alone: The Classic Polar Adventure

(Island Press, Washington, DC)

Jimmy Cornell, World Cruising Routes (Adlard Coles Nautical, UK;

McGraw Hill/International Marine, US)

Cruising Association Handbook

I came late to sailing. Actually, I didnt consciously come to it at all. It crept up on me. David and I had a brief fling with a sailing dinghy in the second year of our marriage a disaster over which it is best to draw a veil. There were some enjoyable boating holidays on British rivers and canals. And then, for our Silver Wedding Anniversary, David asked me if I would like to celebrate with a sailing holiday in the Adriatic. To charter a yacht he needed a Day Skipper certificate. I joined him on the second of his two one-week courses and qualified as Competent Crew. The holiday in the Adriatic was wonderful. Endless sunshine, light winds and no tides to worry about.

After that, my only connection with sailing for several years was David reading yachting magazines. Then, at the age of forty-eight, I found myself joint owner of a 26ft Bermuda-rigged sloop. We kept her at Holyhead in North Wales. Between full-time employment, elderly parents a 90-mile drive away, and one of the worst summers in living memory we got to sail her only very occasionally. It was not remotely like sailing in the Adriatic. North Wales is noted for cold, wet weather and a current so strong that your destination depends on which way the tide happens to be going at the time.

Unfortunately, the deterioration in sailing conditions was matched by a similar falling off in my own performance. Even into our second season I seemed incapable of anticipating what needed to be done. I couldnt judge distances and, short of a gale, never knew where the wind was coming from. I hated heeling and a night on board turned my latent claustrophobia into full, horrific flower. The claustrophobics ultimate nightmare is being buried alive, and the cabin of a small boat is horribly like a coffin.

I also hated putting up and taking down sails on a small rolling deck, and I didnt get on with a tiller. I always pushed when I should have pulled, so I was terrified of gybing accidentally and hurling David overboard, brained by a flying boom. Even if I managed to find him again, would my puny strength be sufficient to lift the dead weight of an unconscious man out of the water? In short, from the moment I stepped aboard our boat I was miserable. David loved her.

After my parents died we began going to the boat every weekend. I would listen to Friday evenings shipping forecast hoping for unfavourable conditions so that we wouldnt go next day. French aristocrats during The Terror probably mounted a tumbrel with only slightly less enthusiasm than I climbed into our car on a Saturday morning. I prayed the sailing phase would pass. At least it didnt cast a pall over my entire year; the British weather put an end to the season by early autumn until late the following spring.

Then, one cold, damp, winter evening as we sat before the fire David wheezing and me aching my worst nightmare happened. He said, Why dont we get a bigger boat, retire early and sail away to a warm climate? It would mean a reduced pension. But living on a boat is cheaper than a house and the benefit to our health would be enormous. As he talked about it he changed before my eyes. The years seemed to fall away.

At 3 oclock next morning I woke to the sound of screaming. It was me, of course. David was very understanding. Our boat went up for sale but there were no plans to buy a larger one. David went into a slow decline and I sank into self-induced guilt.

It was sad. There was so much that I liked about the idea of life afloat: the simplicity; living in the open air; travelling from place to place by water instead of congested roads; anchoring in beautiful, deserted coves; and I longed for a warmer, drier climate. In fact, I didnt mind anything about boats per se, not even the winter maintenance and antifouling. It was just the actual sailing I couldnt stand.

We kept our sloop on a mooring buoy at Holyhead. It was in the days before local entreaties prevailed, and the Irish ferries especially the high-speed Sea Cat roared in and out like the Starship Enterprise. An incoming ferry would send a veritable tidal wave down through the moorings. After it hit the harbour wall at the bottom it would hurtle back up through the moorings again. Then the water still travelling down would meet the water travelling back up and everything crashed about for quite some time.

Next page