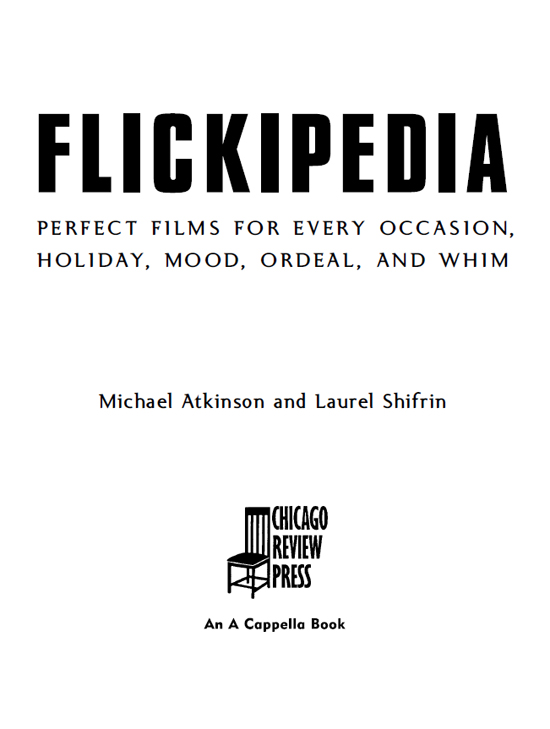

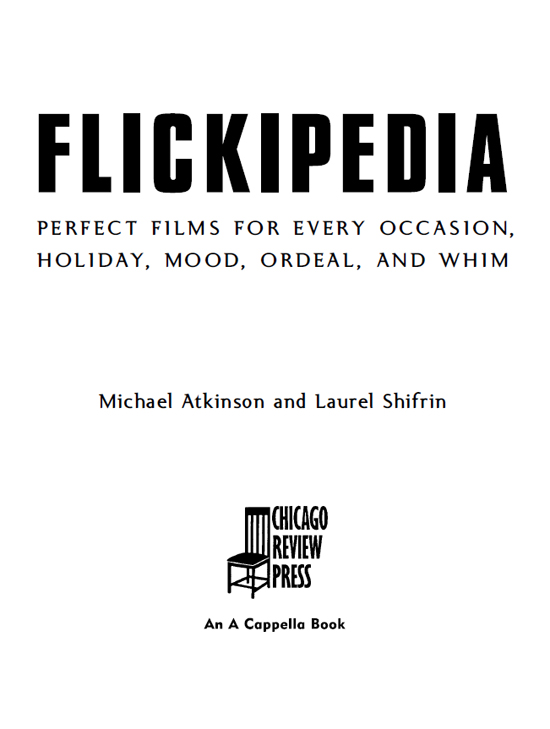

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Atkinson, Michael, 1962

Flickipedia : perfect films for every occasion, holiday, mood, ordeal, and whim / Michael Atkinson and Laurel Shifrin.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-55652-714-2

ISBN-10: 1-55652-714-4

1. Motion picturesCatalogs. 2. Motion picturesPlots, themes, etc. 3. DVD-Video discsCatalogs. I. Shifrin, Laurel. II. Title.

PN1998.A74 2008

016.7914375dc22

2007016467

Cover and interior design: Emily Brackett, Visible Logic

Cover image: Louie Psihoyos/Getty Images

2008 by Michael Atkinson and Laurel Shifrin

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN-13: 978-1-55652-714-2

ISBN-10: 1-55652-714-4

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

For our children, Molly, Riley, and Conor, and our parents, with special gratitude to James Shifrin, who willingly sat through Song of the South three times one summer afternoon in 1972.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This is a book that required a gargantuan amount of communal input-we never trusted ourselves as complete authorities on how and why other people might watch and love movies-and so, at the risk of overlooking someone who has contributed ideas, stories, whims, videos, or inspirations, wed like to thank Frank and Susan Gallagher, Julie Liebow, Anuradha and Michael Magee, James Shifrin, Christopher Wales, Lisa and Tom Murray, Gae Miller, Yuval Taylor, Devon Freeny, Shari Crouch, Barbara Braun, Susan and John Leach, Laurie and Mark Wax, Robin Noble, Roberta Perry, and Nadine Kelly. And our children, who have acquainted us with our fair share of occasions, ordeals, and raptures.

INTRODUCTION

Now more than ever, movies are a way of life. Today its difficult to remember that in previous eras, the cinema represented exclusively a destination-it was somewhere you went, a mini-vacation, a blind date with the sublime. Whatever movies were released to theaters on any given week dictated what you could see, simple as that. Come the late 1950s and beyond, you could catch old films on television, but which old films you could see and when they could be seen were variables the viewer couldnt control. If Gunga Din happened to be playing on one station while a new episode of Gunsmoke aired on another, somebody in the family had to lose the inevitable channel-knob knockdown. In any event, watching a movie via that old black-and-white cathode ray tube was a wretched experience, especially since the films were interrupted with commercials and often recklessly edited to fit into broadcast time slots.

In our pre-videocassette, pre-cable TV lives, movies were a stream we could only randomly raft, with no rudder, anchor, or map; we couldnt direct our viewing course. In this way, our experiences with cinema resembled those with theatrical performances or circuses-if the show came to town, we modified our schedules to catch it. (Lawrence of Arabia is playing at the Rialto! And its only playing at five and nine! Dinners at four! Go, go, go!) It was the same with movies shown on television; they aired when they aired, and it was up to us to accommodate the schedule. Think about that: Then, as now, you could choose what food youd like for dinner, and you could even revisit a restaurant and order a favorite dish over and over again. At bookstores and libraries, you could select any book to read, even if it had been written a century before you were born. You could buy a record of virtually any musical performance, bring it home, and play it any time you wished. But movies were neither easy nor cheap to catch, and they could not be ordered up so conveniently. Like the weather, they simply presented themselves on their own terms, heedless of how well or how poorly they meshed with the general substance of our lives. Movies were our masters, and we were merely the audience.

These days, its a different game: we are in control. With megagoogooplexes showing popular new films on three or more screens every twenty minutes or so, the theatrical experience is now overtly impulsive-people go to the movies without even knowing beforehand which movie theyre going to see or when it starts (as anyone who has witnessed the spectacle of patrons standing in line while indecisively scanning the ticket booth options knows). And the movie-as-outing dynamic constitutes only a sliver of the pie that is todays film-watching experience. A larger slice of that pie is served up in the form of DVDs, videos, cable and satellite television systems, and, increasingly, the Internet. Almost everyone has unlimited access to video rental stores, movies for sale on DVD, and subscription services that can whisk virtually any film on the market right to our mailbox the day after its ordered. We have cable and satellite movie channels that run 24/7, nonstop pay-per-view services, and new technology that provides digitally piped access to a broadening selection of movies any time we want. These days its possible (albeit usually illegal) to download, free of charge, many newly released films that have been uploaded to the Web and watch them on our laptops while we take the train to work, sit in stadium bleachers, wait in a Laundromat, or lounge in the park. Soon enough, we will be able to jack into a cinematic cyberstore and ask to see any movie, at any time, anywhere, on the insides of our eyelids. (By then, movies might not even be movies anymore.)

As it is today, you can, on a whim, rent a viewable copy of virtually any movie you can name for the price of a cheap sandwich; you can own any movie for the price of a restaurant meal-or less. Films are well on their way to becoming universally accessible, regardless of whether or not any given movie is a century, a decade, or a month old. For less than the price of a hardcover novel, you can go online and buy new and old movies, often in sterling digital editions, from Egypt, Brazil, Estonia, and the Philippines. DVD players that handle every international format can now be had for under a C-note.

Gone are the days of movies as fabulous occasions-events around which we must retrofit our busy routines. Today, they are as manageable and selectable to us as fashion, furniture, and food. As a cultural experience, movies now conform to us.

Which is another way of saying that today, movies are subject to the currents of our lives in ways they never have been before. Since the medium itself is at our fingertips, the very nature of film-watching is undergoing a sea change. We now often choose movies the same way we choose music: to accent, heighten, alleviate, expand, contrast, and enhance the flow, peaks, traumas, and doldrums of our daily existence. Certain films must be watched at Halloween, on the brink of baseballs Opening Day, before a wedding, and after a graduation. Times arise for each of us when we absolutely need to watch Duck Soup or Casablanca or Hannah and Her Sisters. Consider the contemporary Christmas use of Its a Wonderful Life and Miracle on 34th Street: these inexhaustible narrative cups of cocoa have become institutionalized rituals, replacing past eras caroling sessions, passionplay pageants, and readings of Hoffmanns Nutcracker. They mean Christmastime to us now. Consider as well the irresistible kitsch tradition of watching The Ten Commandments on TV at Passover, the vivid evocation of summer electricity to be culled from

Next page