CHAPTER

From Colony to

Confederation

THE COLONY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA is isolated. It is separated by mountain, prairie, and Precambrian Shield from the colony of the United Canadas, formerly Canada East (now Quebec) and Canada West (now Ontario). But Sir James Douglas (a.k.a. Black Douglas because his mother was reportedly Creole), chief factor of the Hudsons Bay Company (HBC) and later governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island and the Crown Colony of British Columbia, has a dream: a continental land link between the two settlements. It would bind them together, and none too soon.

Thousands of American prospectors had arrived at the Fraser and Thompson Rivers in 1858, hoping to strike it rich in the Cariboo gold rush. Fearing US expansion north of the forty-ninth parallel, Douglas took action to assert British sovereignty. On August 2, legislation was passed by the British colonial office designating the HBC-administered territory as the new Colony of British Columbia. Its capital would be New Westminster, near the mouth of the Fraser River. Douglas then sought to populate the colony with settlers from the very country that had provided the rowdy problem miners.

He sent word south to California, where a number of free blacks and former slaves were looking for a place to settle. The group sent a delegation to Victoria to investigate, who returned with glowing reports about the attractiveness of the region. Soon after, four hundred black pioneers set sail from San Francisco on the ship Commodore for a new life where they would have the right to vote, sit on juries, and, after seven years, become British citizens. They quickly established themselves and formed a solid core of retail and farming businesses. Later on, several took an interest in discussions to negotiate the colonys entry into Confederation in 1871.

Douglas decided to promote colonial commerce by building a better supply road through the rugged canyon country of the Interior. It would run 644 kilometres, from Fort Yale through the Fraser Gorge, northward to Quesnel, and eastward to Williams Creek. Douglas was sympathetic to the harrowing tales of miners who risked their lives, not to mention their fortunes, crossing whirlpools, First Nations trails, narrow ledges, and steep precipices on foot. He appointed his friend Alexander Anderson to supervise construction.

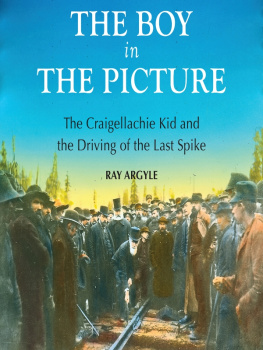

This Great North Road, also known as the Douglas Trail, Lillooet Trail, Harrison Trail, and Lakes Route, would be the primary route to the goldfields of the BC Interior. Initial surveys for the road in 1858 were conducted by the British Corp of Royal Engineers, also called sappers, who completed the two most difficult stretches, from Yale to Boston Bar (ten kilometres) and on to Cooks Ferry along the Thompson River (fifteen kilometres). Much of the road- bed had to be blasted into existence from solid rock. The rest of the route would be completed between 1859 and 1861 by local construction crews. To help finance the trail, Douglas had five hundred men deposit $25 each, a substantial sum back then, to guarantee they would work to the end and not abandon the project when the going got rough. For his part, Douglas would provide pack mules, equipment, and food. When the job was done, the workers deposits would be returned and their supplies delivered to the goldfields. Yes, the men got their money back, but the promised mules never arrived, and the men had to carry all the supplies and equipment themselves for the entire construction period.

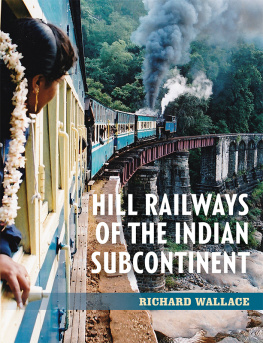

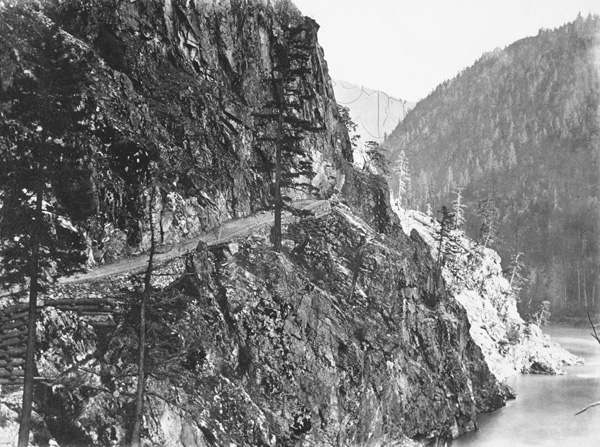

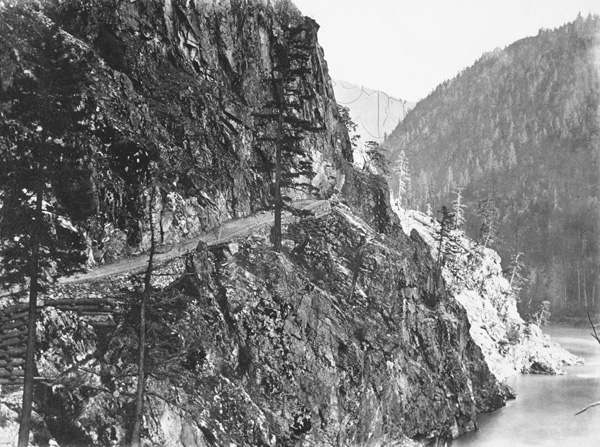

A wagon road in British Columbias Fraser Canyon, circa 1860s.

GLENBOW ARCHIVES NA-674-58

But the colonists wanted a better route from Fort Yale to the goldfields at Barkerville. While the Douglas Trail was useful, it could not handle much freight. So, from 1862 to 1863, a new, improved Cariboo Wagon Road was built. Using picks, shovels, and black powder to break up rock, crews of labourers framed bridges and blasted out footings from the steep sides of the Fraser and Thompson Rivers. At 5.5 metres wide, the completed road to Barkerville would be wide enough for two double-hitched horse teams to pass. Some entrepreneurial contractors received cash subsidies from the colonial government to build the road and, when it was complete, were allowed to charge tolls for its use. But not all endeavours were so lucrative. When government payments were delayed, contractors had to put up their own money to finance construction, and many abandoned the hard work for the dream of instant riches in the goldfields. Others hoped to make their money in supply management. One group invested in twenty-three Bactrian (two-hump) camels, bought for $300 each from the US Camel Corps, for use as pack animals on road construction. Estimated profit: $60,000 a year. After all, they reasoned, camels can carry twice as much and go twice as far per day as mules. The camels travelled from Arizona, where they had been part of a desert survey mission, to San Francisco, where they set sail on the steamer Hermann to Victoria. An article in the May 29, 1862, edition of the British Colonist newspaper stated, They are now acclimated and will eat anything from a pair of pants to a bar of soap. However, the cut-rock trails hurt their soft foot pads, and many camels went lame in spite of being outfitted with rawhide and canvas booties. Also, they bit, kicked, and were more ornery than the mules. In addition, their pungent odour alarmed the horses and mules, who often stampeded when they caught a whiff of their competition. The camels were eventually set free or sold at a loss to ranchers as exotic pets. The last known survivor, called The Lady, died around 1900 while living near Grand Prairie (now Westwold), BC. And so ended the great Canadian Bactrian boondoggle.

Mule trains, covered wagons, stagecoaches, and even oxen used the precarious passages to Barkerville. Inns and stables sprung up every fifteen to twenty kilometres along the two routes, providing food, lodging, and fresh horses. In just one year, $6.5 million worth of gold travelled via the wagon roads from the Interior to the coast. By 1864, both interior routes were operational and advertising in local newspapers. An ad for the Great North Road/Douglas Trail started with Hurrah for the Cariboo! Douglas and Lillooet route is by far the shortest for both animals and men. An ad for the Cariboo Wagon Road claimed, Every person should know that the shortest, best, and cheapest route to the Cariboo Mines is via the Yale and Lytton Wagon Road. Eventually, Douglas hoped, the roadways would be extended to link British Columbia with eastern Canada. Who can foresee what the next ten years may bring forth, he wrote in 1863. An overland Telegraph, surely, and a Railroad on British Territory, probably, the whole way from the Gulf of Georgia to the Atlantic. It was a long time coming, but Douglas was the first politician to champion the building of a national railway and highway.

Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, one of the free blacks who arrived from San Francisco, established a profitable general store, developed a coal mine, founded the first railway in the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii), organized the colonys first all-black militiathe African Riflesthen entered politics. In September 1868 he was Salt Spring Islands elected delegate to the Yale Convention, along with other pro-Confederation supporters like Amor De Cosmos (Victoria) and John Robson (New Westminster). The goal of the convention was to set the conditions for a speedy union of the Colony of BC with the Dominion of Canada. With the gold rush now over, the colonial government was struggling with high debt levels as well as growing discontent among its ten thousand residents. Joining with Canada would be a solution to the colonys predicament.