Preface

Every now and again, upon meeting a person, you know instinctively that whatever that person intends doing will be done well. That proved to be the case when I met George Hughes in Durban towards the end of 1968. My first impression of him was of a fairly desperate young man who was nevertheless fiercely determined to carry out research in a field that he passionately believed was of fundamental importance marine turtles. The obstacles in his way were formidable: no financial support, no base from which to work and no vehicle.

George had come to see me in my capacity as recently appointed director of the South African Association for Marine Biological Research (SAAMBR), a private non-profit company encompassing the Durban Aquarium and Oceanographic Research Institute (ORI), which functioned as a research facility of the University of Natal. In retrospect, it is questionable whether he came to the right person or institution at that particular time. SAAMBR was still reeling from the loss of its charismatic founder-director, Dr Davis Davies, who had died in a motor car accident. The original concept on which SAAMBR had been founded, namely that profits from the aquarium were to fund the ORI research programmes, had not proved feasible. The acquisition of outside funding for research had thus become necessary, but this too was fraught with difficulties. The ORI staff, many of whom hoped to use their research results for achieving masters or doctoral degrees through the University of Natal, were understandably very uncertain of their future.

My job was to get SAAMBR back onto an even keel and I was staggering under the huge load of responsibility. So, when George approached me, my first reaction was, As though I havent got enough hay on my fork. But when we got to chatting I discovered a man with a quick brain and remarkable insight. I told him about the crisis burdening our organisation and of my conviction that, if we were to pull through, we would have to expand our research from studies of sharks and exploitable fish resources to programmes that would enable us to offer scientifically based advice on wider aspects of the management of the coastal zone. George immediately responded that marine turtles are not just dependent on the sea, but are equally dependent on beaches for egg-laying and producing hatchlings. That being the case, he asked, what better research programme do you require for providing advice to provincial authorities on landsea interactions?

I agreed, perhaps a little reluctantly, as I was acutely aware of the fact that coastal ecological processes and landsea interactions go much further than meeting the reproductive requirements of marine turtles. Nevertheless, George had convinced me that the marine-turtle research he was proposing really had to be done. He and I both knew that I was not in a position to offer financial support, let alone a vehicle. What I was prepared to promise, however, was academic supervision and a place to work, which was initially a modest table and chair in a corner of the ORI library.

Bearing in mind my other problems, I also somewhat rashly undertook to seek funds for marine-turtle research under the auspices of the ORI and, if at all possible, to find a suitable vehicle. What I required urgently was a written motivation powerful enough to convince outside funding agencies of the vital importance of marine-turtle research, perhaps as indicators of the health of marine and coastal ecosystems and of their wider management requirements. George sat down at the library table and handed me a document a day later that was one of the most convincing I had ever read.

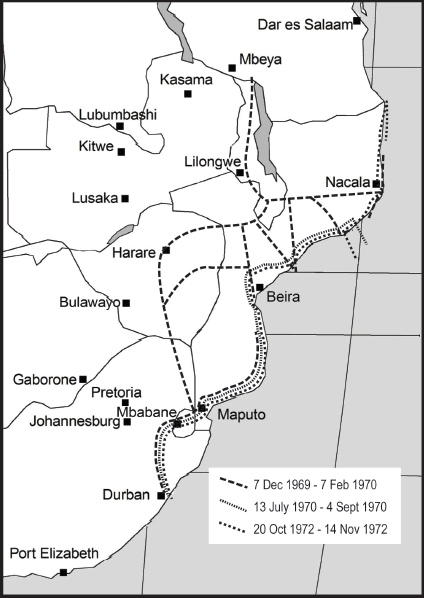

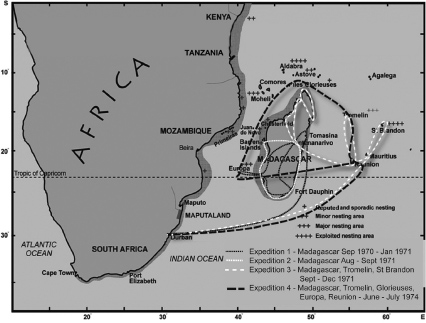

Suffice it to say that we were successful in finding at least some of the required funds, that he augmented these through other applications and that the Southern African Nature Foundation (now WWF-SA) provided funds for a second-hand Land Rover. He aptly named this vehicle The Panda Wagon. George immediately started working with incredible energy studying literature, doing fieldwork on remote beaches, travelling, writing and lecturing. Amazingly, he placed the manuscript of his PhD thesis, The Sea Turtles of South East Africa, on my table scarcely four years later. His research was of central importance as part of the overall activities of the ORI, which were thankfully productive again.

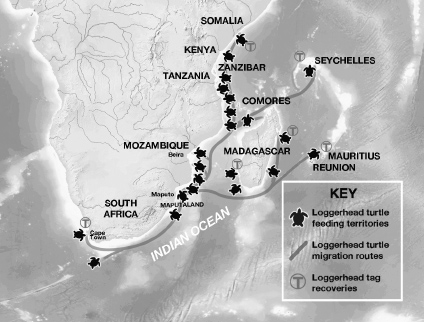

What I was not to know in 1969 was that Georges unflagging dedication and energy would result in him leading marine-turtle research in South Africa for over 40 years, becoming a world-renowned authority in his field and playing a pivotal role in turtle conservation on a global scale. This is remarkable, as much wider and highly demanding responsibilities had in the meantime been placed on his shoulders, inter alia, as senior staff member and eventually CEO of the Natal Parks Board. In later years, especially when I was serving as CEO of WWF-SA, I did not hesitate to draw on his wide experience and knowledge in a way, I made him pay for that Panda Wagon.

It is a privilege to have been asked to write the preface to this remarkable book and I have done so with great pleasure. The chapters that follow tell a story that should not be missed. It tells of determination and dedication, of hardship and joy, of frustration and the overcoming of many difficulties and problems. The reader will be taken to remote and romantic beaches and far-flung corners of the globe. The text is riveting and the story is told with the enthusiasm and humour typical of George. Above all, this book represents a valuable contribution to the national and international annals of marine and coastal science.