ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A former college instructor and high school English teacher, Karen Harper writes contemporary suspense as well as historical novels. Karen and her husband love to travel both in the United States and abroad and, when at home, divide their time between Columbus, Ohio, and Naples, Florida. For additional information, please visit www.karenharperauthor.com.

AUTHORS NOTE

The third biggest mystery about William Shakespeare (after endless arguments on who really wrote the plays and what he did during the lost years between the time he left grammar school and first began to act in London) concerns whom he married. Its accepted by most historians that he wed Anne Hathway [sic] of Stratford in the dioces [sic] of Worcester maiden. (All of the entries are originally in Latin.) But the same official record, which is kept in the Worcestershire Record Office today, is documentary proof that, on the previous day, he was issued a marriage license, called a marriage bond, to wed Anne Whateley of Temple Grafton.

Many have tried to shuffle off Anne Whateley as a mistake of the pen or the ear, but they conveniently ignore that the recorder in Worcester (both entries are in the same handwriting) also mistook the words Temple Grafton for Stratford and failed to cross out or correct the previous days error of the Anne Whateley/Wm Shaxpere entry when William Shagspere/Anne Hathway was written in. The Shakespeare name is misspelled in both cases, so that cant weigh in on one side or the other; the Elizabethans cared little for standardized spelling. Shakespeare signed his own name various ways, including the two mentioned.

Besides unstandardized Elizabethan spellings, there are other challenges to Elizabethan-era research. Dates are always a problem since the Julian calendar was used until 1582, when the switch was made to the Gregorian, which dropped ten days from the previous records. But more confusing is that their new year began on Lady Day (March 25), despite the fact they also called January 1 New Years Day. So, dual dating for events can occur.

I have tried not to take liberties with history, although I have Marlowes plays performed at times slightly different from what some sources claim. Tamburlaine the Great was probably first performed in 1587 instead of early 1588, and by the Lord Admirals Men at the Rose. Doctor Faustus was most likely performed in the early 1590s instead of 1588.

I am indebted for help in having the entire marriage bond for my study to John France, Senior Microfiler/Digitiser, County Hall, Worcestershire Record Office, Worcester, Worcestershire, United Kingdom. At the writing of this note, part of the bond is available for viewing on the website http://home.att.net/~mleary/positive.htm.

Over the centuries, certain scholars have stood up for the possibility that there was a second Anne in Will Shakespeares life. The Man Shakespeare (1909) by Frank Harris gives an extensive array of reasons supporting Anne Whateley; a 1917 play, The Good Men Do, by Hubert Osborne hangs its plot on his belief in the dual Annes. Other writers and historians, such as Ivor Brown and Anthony Burgess in his 1970 critical studies on Shakespeare, make a case for the second Anne. I agree, relying as much on what seemed to be missing from Wills relationship with Anne Hathaway as with the research on Wills life on which I base this story. Will could well have had another wife.

I have studied the Elizabethan period for many years; wrote my masters degree thesis about one of Shakespeares plays, Alls Well That Ends Well; and have written numerous novels set in that period, including a nine-book historical mystery series with Queen Elizabeth I herself as the amateur sleuth. I have been to London and Stratford-Upon-the-Avon many times, always concentrating on Elizabethan events and sites. When I taught British literature at the high school level, I helped organize an Elizabethan festival in which the students played many parts. In short, for some reason, I am drawn to the Tudor era and its fascinating people.

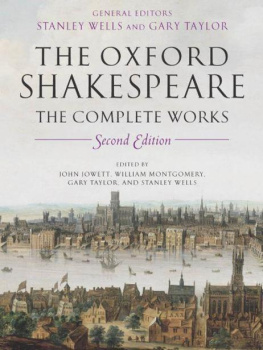

Of the many books on Shakespeares life that I have read as background and inspiration before I wrote Anne Whateleys story, three were of special help to me: Shakespeare: The Biography, by Peter Ackroyd ; Shakespeare, by Michael Wood (which was also an excellent Public Broadcasting miniseries); and Will in the World, by Stephen Greenblatt. Many people interpret the Bard of Avons life differently with, as the playwright himself said, infinite variety.

Of my many books on Elizabeth Tudor, I leaned most heavily on Alison Weirs The Life of Elizabeth I.

Such minor things in this novel as the portrait of the playwright as a young man and the W.S. signet ring with the lovers knot do exist. Now in the possession of the John Ryland University Library in Manchester, England, the painting is usually called the Grafton Portrait because it was found in a home in Temple Grafton. I like to imagine that Susannah Hall, after her mother died, gave it back to Anne Whateley. The ring was discovered in 1810 in a field close to Holy Trinity churchyard; it is in the possession of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford.

Also, it is fact that a young Stratford woman named Katherine Hamlett drowned in the Avon in 1580, leaving her milk pail on the bank. Of such small details are big stories made.

Sadly, the Globe and Blackfriars theatres were pulled down in 1644 and 1655, respectively, so that tenement buildings could be erected. But, of course, the Globe was rebuilt in modern times and Shakespeares plays live on there and in many other venues. And so, although this novel is fiction, the pieces that support the story are as factual as research and serious speculation can make them.

Despite my years of research in the Elizabethan era, I especially noted several fascinating and surprising truths while writing this novel. Marriage in the old days was often delayed until a persons mid-twenties, and a surprising proportion never wed, including several of Shakespeares brothers. Illegitimacy rates were quite low because what we would call shotgun marriages were commonagain a statistic with which Will Shakespeare was personally involved. Also my reading reminded me how many Elizabethans died early, not only as infants but as young people. I have not exaggerated the death toll of the Shakespeares or the Davenants. People were middle-aged at thirty, and someone like the queen who lived to be seventy was quite remarkable.

Although we do not live in an age where youth and health are brief candle[s] and radish poultices are used to cure ills, perhaps we should yet be reminded to use well our hour upon the stage.

Karen Harper

June 2008

CHAPTER ONE

My entrance to this world was in the same year as Wills, 1564, though he made an appearance in the spring and I in the autumn. Looking back, I can say that the most startling discovery of my early life was how gentle and lovely lay the land where I was reared but how fierce and brutal the blows of life that soon assailed me.

Among other local children, I always knew that I was different. In the heart of the sweet countryside of central England, where most folk were blue- or green-eyed, fair-skinned and light-haired, I had snapping dark eyes under brows of inky arches, a tawny complexion and a thick, unruly mane of raven-black hair. Yet I believe I was comely in an exotic way, like some rare bird the winds have blown off course. How could I be else with an Italian mother? She was, of course, Catholic born and bred, which she kept quiet in Glorianas Protestant England. I yet possess my mothers violet-tinted glass rosary beads from Venice; I pretend they are a crystal necklace she bequeathed me, but these dangerous days, I wear it only with my night rail in my bedchamber.