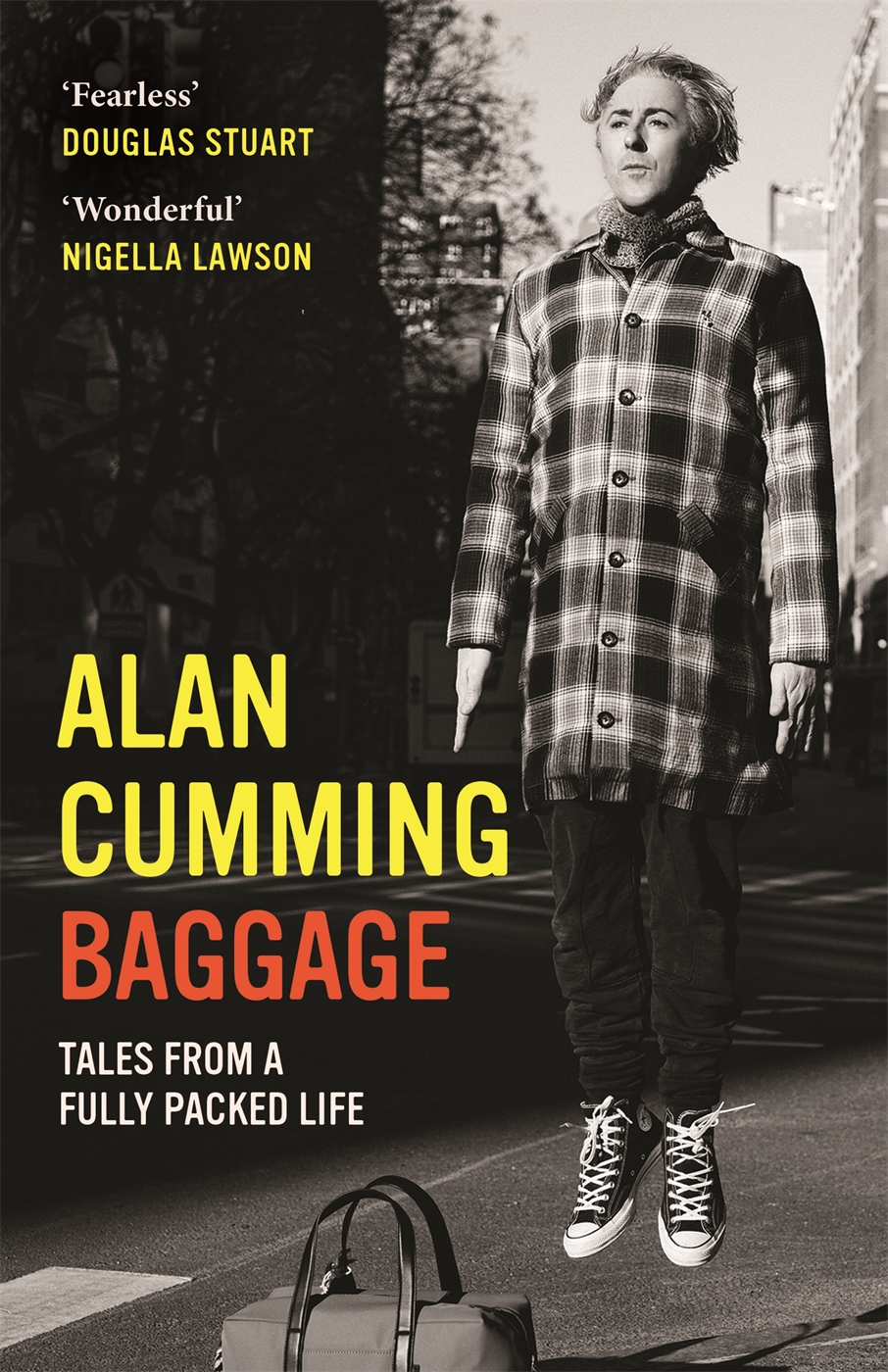

Alan Cummings many awards for his stage and screen work include the Tony, Olivier, BAFTA and Emmy. He is the author of two childrens books, a book of photographs and stories, a novel and a memoir, Not My Father's Son. He is a podcaster (Alan Cummings Shelves) and an amateur barman (NYCs Club Cumming).

@alancumming | alancumming.com

ALSO BY ALAN CUMMING

NONFICTION

Not My Fathers Son

FICTION

Tommys Tale

The paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2022 by Canongate Books

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

First published in the USA in 2021 by HarperCollins

canongate.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2021 by Canongate Books

Copyright Alan Cumming, 2021

The right of Alan Cumming to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 83885 667 0

eISBN 978 1 83885 665 6

Designed by Paula Russell Szafranski

For my granny,

who made me realise it was okay to be different

BAGGAGE

PROLOGUE

Shakespeare calls memory the warder of the brain and despite the fact that it is Lady Macbeth who brings up this idea while bulldozing her husband into murdering their current house guest, I find it very comforting.

The notion that my increasingly spotty reminiscences of tumbling through life will somehow protect me, like a cerebral condom, from repeating old, negative patterns or embarking on perilous new ones that my gung ho, adolescent brain would otherwise have dived straight into has, for me, coloured the Bards fiend-like queen with an Oprah-like hue.

It makes sense that what we have experienced in the past, and how we have analysed and grown from it enables, or at least helps us, to have better judgement. Right? Thats what we call the benefit of hindsight. But what if your memory isnt so accurate? What if the stuff supposedly protecting your brain is actually deluding you into making the same mistakes again and again? Even a cerebral condom can break, right? I know I have, on several occasions throughout my life, repeated the exact same patterns of behaviour that previously made me unhappy to the point of despair. So much for the warder of the brain, huh?!

Every day more experiences and lessons are poured into our memory banks, rearranging and augmenting our views and actions. And if we accept that sometimes we simply choose to ignore our memorys lessons, then we must also agree that memory itself, not just our relationship to it, is ever shifting.

Have you ever wondered if you remember an incident from your childhood because you actually recall it or merely because youve heard others talk about it, or seen a photograph of it? My first memory is of a leaf falling down from a tree and landing beside me in my pram. I do genuinely remember seeing that happen but did it really?! Do I perhaps remember it because my mum once mentioned something about a leaf landing in my pram, or I remember seeing an old photo of me sitting in my pram beneath a tree on an autumn day? But did what I recall actually happen? Did my mum really once talk of it? Was there ever such a photo? Truly, how reliable can any of our memories be?

One single memory can never be a true touchstone, and perhaps even a collection of remembrances of the same eventboth ours and others, as faulty and varied as they all may beis not the true function of memory, either. Rather it is what we do with those memories, how we let them accumulate then process through our minds so we can learn from them. Isnt that really what memory is, or should be? Not just for recall but for growth? The repetition of memory is wisdom, but how we act upon that wisdom is the making or undoing of a good life.

Nowadays I see memory differently: its not something to be dragged out of the past and dropped at my feet like some subconscious carcass. Now I look forward to meeting up with people I havent seen in decades and reminiscing, for I know that they will unlock doors in my mind, and I will relive moments we had together that I otherwise might never have accessed again. I have learned that memory is collective and now memories are a gift awaiting me in the future, not the past. Each time a new one is coaxed into the light from the unchartered mists of my mind, I am buoyed and fascinated. Even the bad ones are another piece of the jigsaw of the life I inhabit. I welcome them all.

Heres how I think about memory today: picture some spaghetti cooking in a pot of boiling water and imagine the entire contents of that pot are my life experiences. Now picture the spaghetti being drained through a colander, and that colander is my brain. What is left, the drained spaghetti, is my memory.

Yes, huge swaths of what weve lived just drain away, but I like to think theyre the boring bits, the routine, the day-to-day minutiae or the stuff we just didnt register all that much at the time. Whats leftthe spaghettiare the remarkable bits, the bits that arrested us. And what makes life interesting is that we all get arrested for different reasons, by different things.

This gratuitous culinary metaphor also functions as a disclaimer to remind you that perhaps not every detail of what I am about to tell you will be completely and utterly accurate. But how could it be? My heads full of spaghetti!

Whenever anyone asks me how I am, I always reply, Still alive!

Each day is a prize for me. Not a gift, mind you. A gift is given but a prize must be won.

There is absolutely no logical reason why I am herein this life, in this house, in this country, writing this book, having been asked to write this book. None. The life trajectory my nationality, class, and circumstances portended for me was not even remotely close to the one I now navigate. But logic is a science and living is an art.

For years people would tell me I was brave or courageous, thank me for having inspired them or making them felt heard or seen. What they meant was that by living an open life as a queer manand a famous oneI was somehow empowering them. I felt fraudulent being so vaunted for merely enjoying living my life, but I began to comprehend the utter thirst so many have to feel represented, especially when they do not have the option to express their true selves. And I could relate, for I too had a secret.

My first memoir was written without guile and out of utter need to tell my tale, to be heard, to be seen. I wrote of my experiences as a little boy dealing with a very disturbed and dangerous adult man whose splintered psyche rained down such physical and emotional violence it startled even me as I recounted its horror on the page. That man was my father. But the title of the book, Not My Fathers Son, was a gesture of succour, an assurance that I had not only managed to transcend those early days but indeed, in spite of them, bloom.

Writing compounded my healing and learning. Setting experiences down meant I had to analyse and quantify them. It was the ultimate breaking of a cycle, for in sharing the breaking of mine, I have empowered others to shatter theirs: every single day still, so many years later, I hear from people that my words galvanised themto confront their abusers, to confront their memories, to reveal and reckon with what had been their shame. I learned the power of my words. I was reminded of the absolute duty of authenticity. That in telling my story, by being fully and openly me in all areas of my life, I could empower so many was initially frightening, like a wildfire I had started but could not control. But if the utter liberation I felt in telling my truth could be manifested in others lives, I felt at peace. I felt, in fact, I had found my calling.