Table of Contents

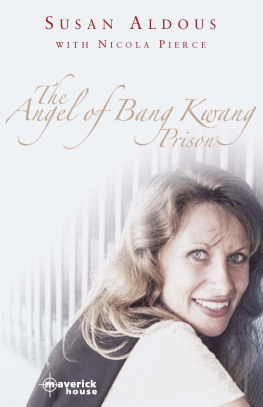

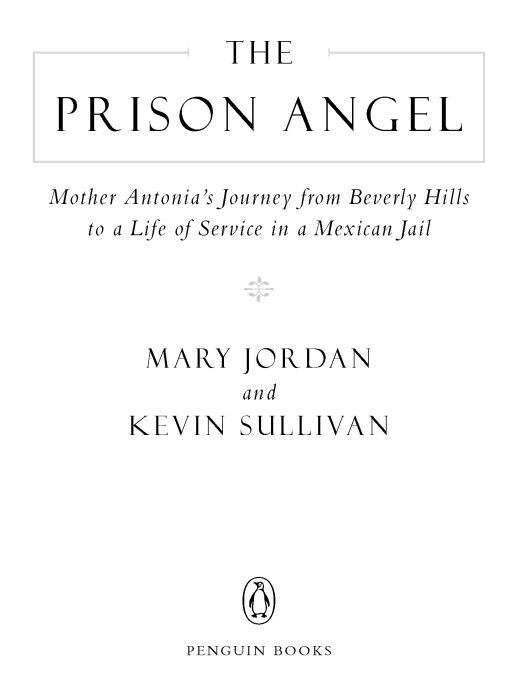

Praise for The Prison Angel

The authors tell her stories simply, and with dignity, allowing Mother Antonias passionate determination to come through without clich and beautifully illustrating her rare approach to societys wayward and forgotten.

Publishers Weekly

Admirably evoked... Were indebted to [ Jordan and Sullivan] for calling our attention to this remarkable woman.

National Catholic Reporter

Thanks to the authors, this astonishing story of how one womans journey of spiritual growth has transformed innumerable lives is now available as an inspiration to all. Highly recommended.

Library Journal

Jordan and Sullivan have delivered their characteristic hard-hitting reporting.... [The book] offers a strong dose of inspiration.... No one will be untouched by this remarkable book about a remarkable woman.

The Washington Post Book

World

An effective portrayal of the human side of Mexicos broken justice system.

Business Week

An inspiring story of one womans compassion and her own journey of spiritual growth.

Booklist

A book both moving and important in its depiction of an exceptional life.... Readers will leave this nuns company reluctantly and thank Jordan and Sullivan for making her remarkable life visible in a jaded world.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer

Inspiring

Kirkus Reviews

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE PRISON ANGEL

Mary Jordan and Kevin Sullivan are foreign correspondents for The Washington Post. After postings in Tokyo and Mexico City they took over the newspapers London bureau in the summer of 2005. They won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for international reporting for their coverage of Mexicos criminal justice system. They are married and have two children.

For our parents

and for Kate and Tom

Preface

In early 2002, we asked a young woman on Islas Maras, a prison in the Pacific Ocean about 100 miles off the Mexican coast, how she liked being an inmate there. She bubbled on about the beautiful ocean setting and the fresh air, and she said it was sure better than the last prison shed been in. She had come from La Mesa prison in Tijuana, the border city across from San Diego, where she said the conditions were brutal.

The only good thing about that place was that Irish nun, she said.

Come again?

She told us about a nun, an Irishwoman she said, who lived in a cell alongside the inmates, helping to feed and clothe them and protect them from abuse by guards.

I miss talking to her, she said.

We wrote ourselves a note: Find nun who lives in prison.

A few weeks later, we stood outside the imposing front gate of La Mesa, a fortress of twenty-five-foot walls in the middle of a downtown Tijuana neighborhood.

Mother Antonia came to greet us at the gate, a cheery little woman in a black-and-white habit.

We sat with her, and she told us about her life, about how she was raised as a well-off girl in Beverly Hills with neighbors like Spencer Tracy. (She turned out to be Irish American.) She talked about how she spent three decades as a suburban mom in Los Angeles, raising seven children.

She told us about poor people locked up for years for stealing food, about the famous drug dealers whose bullet-blasted bodies she had washed and dressed for burial. We listened, and we were hooked. Together, we have been interviewing people as journalists for more than forty years. We have interviewed presidents and rock stars, survivors of typhoons in India, and people tortured by the Taliban in Afghanistan. We had never heard a story quite like hers, a story of such powerful goodness. This was a tale that needed telling.

For starters, we wrote a story about her life that appeared on the front page of The Washington Post on April 10, 2002. In the weeks that followed, letters and e-mails came pouring in. People wanted to know how to help her. A gay Catholic man wrote to say his faith had been renewed by the story of how a divorced woman had not let the churchs rules diminish her faith. An old boyfriend, who had not seen her since World War II scuttled their plans for a life together, saw the story and wrote to herin care of the prisonand they talked for the first time in fifty-seven years. Kathleen Todora, a widow from Louisiana, read the story, packed her bags, and drove to Tijuana to join Mother Antonias mission.

That response confirmed what we already knew: Mother Antonia was rare, and those whose lives are touched by hers are affected forever. She gets under your skin, and she changes you, whether its seeing a little more humanity in a street beggar, or no longer being able to look at a Starbucks caffe latte without imagining how much better that four dollars could have been used.

This book is a work of journalism, not an as told to story. Mother Antonia is the first to say she isnt perfect. She has struggled with real life problems; she has known the highs of marrying for love and lows of divorce when that love dies. Suffering from poor health for a lifetime, she has ignored her ailments, grabbed hold of her gifts, and used them to do extraordinary things. She is the happiest person we have ever met.

For almost three years, we have conducted hundreds of hours of interviews with Mother Antonia. We gave her a tape recorder and tapes and asked her to tell us the stories of her life. We have sat with her in the prison and in her small house nearby filled with an eclectic mix of women: inmates just leaving the prison; women receiving cancer treatments; and mothers, daughters, and girlfriends who have come long distances to visit men in prison and have no money to stay anywhere else.

We have also talked about Mother Antonia with her friends, family, bishops, inmates, guards, wardens, police chiefs, DEA agents, Army generals, and even Benjamn Arellano Flix, one of Mexicos most notorious drug traffickers. In all possible instances, we have checked and double-checked their stories with witnesses, public records, old newspaper clippings from the Library of Congress, and even in an eye-opening interview with an ultrasecret DEA informant we were introduced to only as Comandante X. We have been amazed at the accuracy of Mother Antonias memories, even those from a half-century ago. She remembered Eddie Cantors street address from the 1930s. And she remembered it right.

People of all faiths, or of no faith, are drawn to Mother Antonias message of inclusion. She loves the Catholic Church, but not all its rules. She wears over her heart a cross interlaced with the Star of David, a symbol of her devotion to the Jewish faith and the lesson she learned from the Holocaust as a young girl, that no one should stand by silently in the face of suffering. Some of her most generous financial supporters are Evangelical Christians in California. Mother Antonia thinks God doesnt check IDs at Heavens gate.

In the end, this is the story of a woman who followed a dream later in life. She was fifty when she traded suburban Los Angeles for La Mesa. Mother Antonias hope is that she will be joined by more and more women, and someday also men, who are looking for ways to give meaning to their later years. She believes that the world is full of older people with long experience who now want to help others.

![HMP Belmarsh - A prison diary. [Volume one. Belmarsh: hell]](/uploads/posts/book/212654/thumbs/hmp-belmarsh-a-prison-diary-volume-one.jpg)