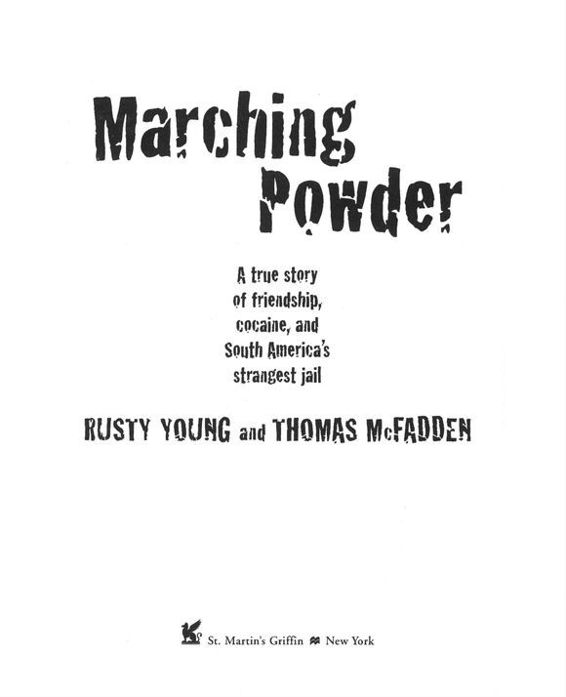

RUSTY

T hree days before I was arrested and ordered to leave the Republic of Bolivia, guards at San Pedro prison in La Paz caught me with several micro-cassettes hidden down my pants. I was on my way out of the main gates when they conducted the search. They were looking for cocaine, which is what most visitors smuggled out of San Pedro, and were slightly confused by what they found in its stead.

At the time, I believed I had got away with it by convincing the guards that the cassettes were the latest in Western music technology. However, three days later I was arrested on an unrelated charge. To this day, I do not know whether the police had found out about the book I was writing for Thomas McFadden, the prisons most famous inmate, or whether they thought I was a spy of some description. Either way, they were extremely suspicious as to why a foreign lawyer on a tourist visa had been staying voluntarily in Bolivias main penitentiary facility for three months.

During the first month of my stay in the prison I had told the guards at the gate that I was Thomass cousin. For the second month, the guards probably assumed I was there in order to do drugs, like the other Western tourists who arrived at San Pedro carrying their guidebooks and departed wearing their sunglasses. By the third month, the guards let me in and out without question. Provided I paid them enough money, they believed whatever I told them.

Then they arrested me. Ironically, the arresting officer chose bribery as the pretext. He was the same major I had been bribing every week since I had been there. I slipped him the customary twenty bolivianos as we shook hands on my way in, but on that occasion he looked at me as if we had never met before.

Give me your passport, he said, glaring incredulously at the folded note that had appeared in his hand. I did as I was told. Now follow me.

It was a Saturday morning when they arrested me. They placed me in the police holding cells to stew for a while. Monday was a public holiday. The tourist police would not be able to process my crime until Tuesday, they said. I would have to wait for three days. No, I could not leave my passport as collateral and come back on Tuesday. No, I could not have any food I was under investigation. No, I could not make a phone call this was not a Hollywood movie.

Having spent three months in the prison, I wasnt particularly rattled by any of this. I had been listening to Thomass stories about the Bolivian police for long enough to know that it would end up in a bribe. When they asked which hotel I was staying at and hinted that they would search my room and find drugs, I gave them a phoney address. When they left me alone in the cell, I went through my wallet and found the card of the hostel where one of my traveller friends was staying. They would not have needed to plant anything there; he had smuggled ten grams of cocaine out of the prison in a book the day before. I ripped the hostel card to shreds and then chewed it into a soggy ball, just like Thomas had done nearly five years earlier after he was busted at La Pazs airport with five kilos of cocaine concealed in his luggage.

Four hours later, I heard the police coming for me. I thought about my dead cat in order to induce some tears and continued to pretend not to speak much Spanish. Now that he had cracked me, the captain at the police station offered me a deal.

You have fallen badly, seor gringo. Bribery is a very serious crime in this country. You will have to pay. I nodded solemnly. My tears of fear mixed with tears of gratitude and irony, but I tried not to smile.

I managed to bargain the captain down by emptying my pockets and showing him all the money I had on me. The rest of my money was hidden in my socks in three rolls. I knew how much was in each roll in the event that the negotiation skills I had developed while in San Pedro required greater reserves. The captain had one more condition before he would make my charge sheet disappear: I had to agree to leave the country and never return. That would mean the end of work on the book that Thomas and I were writing.

If I see you in San Pedro prison again, the captain threatened, Ill send you to jail. Comprende?

I nodded. Despite its paradoxical phraseology, I knew this threat was serious. The police wanted to scare me off from whatever it was I was doing with the micro-cassettes. I left immediately for the dirty town of Desaguadero, on the Peruvian border. As soon as I arrived, I got stamps in my passport as proof to show the captain that I had at least obeyed the first part of his instructions. Peruvian immigration laws prevented me from officially leaving the country on the same day as I entered it, but that did not stop me from walking back across the border to get a hotel for the night on the Bolivian side, which was cheaper.

I rang Thomas in prison. I had to call his mobile phone, since the inmates in the four-star section of San Pedro where Thomas had his apartment were not allowed land lines. I had not told him about the guards finding the micro-cassettes, which we were using to record our interviews, because I knew he would have been angry.

This isnt a game, Rusty, he had lectured me on numerous occasions. This is my life youre playing with here. These people are not joking, man.

When he answered the phone, Thomas was unsympathetic.

Where were you, man? I waited all day.

I told him Id been arrested.

Thanks a lot, man. You ruined my life, he said, before hanging up on me.

I knew he would want me to call again, so I waited half an hour before buying another phone card. I didnt even need to say who was calling.

You is a stupid kid, Rusty, Thomas said, as soon as he picked up the phone. I could tell by his voice that he had taken a few lines of coke. I told you this would happen if you wasnt careful. The coke seemed to have calmed him down a little.

So, what am I going to do? I asked him.

We have to bribe them again. Well have to call the governor of the whole prison. Thats going to be an expensive bribe, man.

When Thomas said we in reference to spending money, he always meant that it would be my money we would spend.

I got my Peruvian exit stamp the following morning and then returned to San Pedro prison. Thomas had already arranged for me to bribe the governor. It cost us one hundred US dollars. I continued to make flippant remarks until a week later when the police torturedThomass friend Samir to death, then left him hanging in his prison cell by a bed sheet in order to make it look like suicide. Samir had been threatening to write a letter to parliament exposing high-level corruption in the police force. Imagine if they knew what Thomas and I were doing. I had not taken the danger seriously until then.

The story of Samirs death was front-page news. When I showed the article to Thomas, he didnt look at it.

I told you these people are not joking, man. You didnt believe me.

I had heard about Thomas McFadden long before I met him. A group of Israelis I met while trekking to the ancient Incan ruins of Machu Picchu had spoken of him with reverence. An Australian couple had told me about him during an Amazon jungle tour out of Rurrenabaque. Indeed, his fame had spread all the way along the South American backpacking circuit affectionately dubbed by travellers the gringo trail, which extends from Tierra del Fuego in Argentina up to Santa Marta in Colombia.