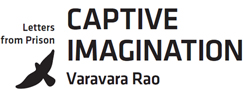

Poet, Marxist critic and activist, Varavara Rao (VV) has been continually persecuted by the state and intermittently imprisoned since 1973, but he never stopped writing during all these decades, even from within prison. When he was subjected to one thousand days of solitary confinement during 198589 in Secunderabad Jail, a leading national daily invited him to write about his prison experiences.

While prison writing is a hoary tradition, no writer has had the opportunity to publish his writings from jail. VV, however, did meet the demands placed on him as a writer, despite constraints of censorship by jail authorities and the Intelligence section.

He decided to test his creative powers in jail on the touchstone of his readers response and expressed himself in a series of thirteen remarkable essays on imprisonment, from prison.

Collected for the first time in English, the essays in Captive Imagination are fiercely personal in their experience and evocatively universal in their expression.

Varavara Rao is a well-known Telugu poet and an ideologue of Maoist politics.

He is one of the founders of VIRASAM Revolutionary Writers Association, the first of its kind in India, directly inspired by the Naxalbari and Srikakulam adivasi peasant struggles. He has published ten volumes of poetry and his work has been translated into a number of Indian languages. He was also one of the spokespersons in the first ever talks held between the Maoists and the Andhra Pradesh government in 2000.

Captive Imagination is simply phenomenal in the quality of its writing, thought, politics and cultural reach.

Ngugi wa Thiongo

Translated from Telugu by

Vasant Kannabiran, K. Balagopal, M.T. Khan,

K. Jitendra Babu, N. Venugopal and Jaganmohana Chari

Foreword

by

Ngugi wa Thiongo

PENGUIN

VIKING

VIKING

UK | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This collection published 2010

Copyright Varavara Rao 2010

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-670-08257-5

This digital edition published in 2016.

e-ISBN: 978-8-184-75226-7

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

CONTENTS

by Ngugi wa Thiongo

Foreword

That which

the imagination

makes possible

Ngugi wa Thiongo

Among the many telling stories that Varavara Rao narrates in these brilliantly written prison letters is that of an illiterate prisoner who squats by a heap of newspapers each of which he holds in his hands and then stares blankly at for a long time. Asked about it, he says that he is just looking at the pictures. Rao reads more into this: through the senses of touch, sight, smell and feeling, the prisoner can certainly grasp some news. The news may not be necessarily what is in the newspaper but does exist in another realityin some ways more real and vitalprovided by his imagination. His imagination carries him into the spirit of the letterswhich he cannot readand in so doing, takes him beyond the walls of his confinement. In the mans imagination, the words become the world.

The title, Captive Imagination, is ironic. Of all the human attributes, the imagination is the most central and most human. An architect visualizes a building before he captures it on paper for the builder. Without imagination, we cannot visualize the past or the future. Religion would be impossible, for how would one visualize deities except through imagination? How would one undertake a purposeful journey without imagination, the capacity to picture our destination long before we get there? The arts and the imagination are dialectically linked. Imagination makes possible the arts. The arts feed the imagination in the same way that food nourishes the body and ethics the soul. The writer, the singer, the sculptorthe artist in general, symbolizes and speaks to the power of imagination to intimate possibilities even within apparently impossible situations. That is why, time and again, the state tries to imprison the artist, to hold captive the imagination. But imagination has the capacity to break free from temporal and spatial confinement. Imagination breaks free from captivity and roams in time and space.

The real subject of these letters is imagination. In prison, Rao looks for meaning even in the apparently trivial and inconsequential. He looks at birds that fly and they speak to him of freedom. He looks at nature, flowers, and he sees images of motion, change and growth. Through the windows, Rao can behold the enormity of a sky that no prison can contain. Nature that speaks of endless motion, interconnection of being and endless possibilities is his companion. He also finds companionship in history: from a whole array of Indian writers of times past and present to imprisoned artists and intellectuals across cultures and continents. These voices from the world range from the Korean poet Kim Chi-ha to the African American George Jackson. Nelson Mandela speaks to him from South Africa as the very image of a spirit that would not die or quit the struggle. Pablo Neruda from Chile tells him that the word is born in blood, the word is blood itself. In the American Walt Whitman he hears the call and the challenge of solidarity: Who but I should be the poet of comrades? The Russian Yevtushenko tells him that a poets word should cut through silence like a diamond. In solitary confinement, it is Faiz Ahmed Faiz of Pakistan who assures him that those who brew the poison of cruelty may put out the lamps where lovers meet but they cannot blind the moon. Varavara Rao experiences this and exalts in recognition of the truth in Faizs words:

Faiz has written this poem for me, in this condition. Yesterday afternoon, marking the beginnings of summer, I bathed and walked in the yard. I saw the sun set before me and the moon rising behind me. The cool breeze blowing in the moons farewell after lock-up is exactly as Faiz describes iton the roofs high crest the loving hand of moonlight rests. As the lights go off, the moonlight glides like mercury over my body and mind.

On a personal level, I felt touched that my own words, forged in similar places of confinement in Kenya, reached him.

These letters from prison are really from the heartland of resistance. They are a celebration of words that sing solidarity with those who struggle against confinement in and outside prison walls. They are lyrics to freedom and social justice everywhere. Imprisoned in order not to make history with others, the poet, through words, still makes history. Raos book, Captive Imagination, stands in the frontline of resistance literature in the world. It speaks to the human will to freedom.