Table of Contents

Guide

Table of Contents

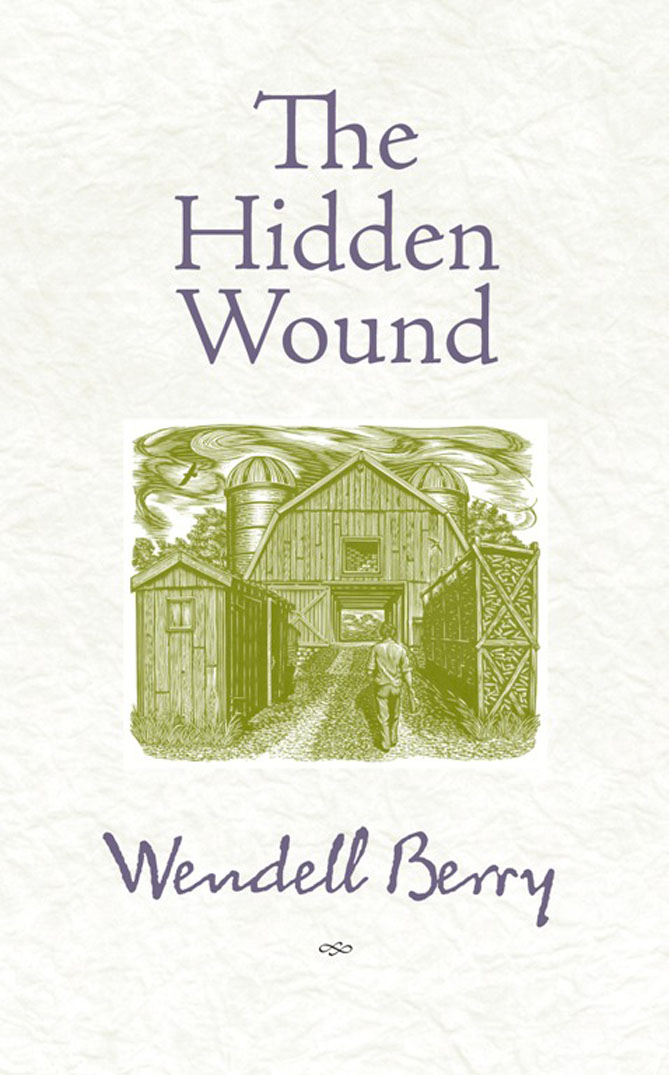

In memory of

Nick Watkins

&

Aunt Georgie Ashby

But I want to tell you something. This pattern, this system that the white man created, of teaching Negroes to hide the truth from him behind a facade of grinning, yessir-bossing, foot-shuffling and headscratchingthat system has done the American white man more harm than an invading army would do to him.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X

... wanting good government in their own states, they first established order in their own families; wanting order in the home, they first disciplined themselves; desiring self-discipline, they rectified their own hearts; and wanting to rectify their hearts, they sought precise verbal definitions of their inarticulate thoughts (the tones given off by the heart) ...

Confucius, The Great Digest (translated by Ezra Pound)

... I amthe brutal thing itself.

William Carlos Williams, In the American Grain

1

It occurs to me that, for a man whose life from the beginning has been conditioned by the lives of black people, I have had surprisingly little to say about them in my other writings. Perhaps this is justifiablethere is certainly no requirement that a writer deal with any particular subjectand yet it has been an avoidance. When I have written about them before I have felt that I was doing little more than putting down a mark, leaving an opening, that I would later have to go back to and fill. For whatever reasons, good or bad, I have been unwilling until now to open in myself what I have known all along to be a wounda historical wound, prepared centuries ago to come alive in me at my birth like a hereditary disease, and to be augmented and deepened by my life. If I had thought it was only the black people who have suffered from the years of slavery and racism, then I could have dealt fully with the matter long ago; I could have filled myself with pity for them, and would no doubt have enjoyed it a great deal and thought highly of myself. But I am sure it is not so simple as that. If white people have suffered less obviously from racism than black people, they have nevertheless suffered greatly; the cost has been greater perhaps than we can yet know. If the white man has inflicted the wound of racism upon black men, the cost has been that he would receive the mirror image of that wound into himself. As the master, or as a member of the dominant race, he has felt little compulsion to acknowledge it or speak of it; the more painful it has grown the more deeply he has hidden it within himself. But the wound is there, and it is a profound disorder, as great a damage in his mind as it is in his society.

This wound is in me, as complex and deep in my flesh as blood and nerves. I have borne it all my life, with varying degrees of consciousness, but always carefully, always with the most delicate consideration for the pain I would feel if I were somehow forced to acknowledge it. But now I am increasingly aware of the opposite compulsion. I want to know, as fully and exactly as I can, what the wound is and how much I am suffering from it. And I want to be cured; I want to be free of the wound myself, and I do not want to pass it on to my children. Perhaps this is only wishful thinking; perhaps such a thing is not to be done by one man, or in one generation. Surely a man would have to be almost dangerously proud to think himself capable of it. And so maybe I am really saying only that I feel an obligation to make the attempt, and that I know if I fail to make at least the attempt I forfeit any right to hope that the world will become better than it is now.

Stories that have come down to me tell me that on both sides of my family there were slaveholders. And it is probably of some importance to try to say exactly how these stories were handed down. It would be easy to allow the impression that the past and its assumptions were deliberately and consciously planted in my mind by my elders. But that is not at all the way it was. The various households of my family were always visiting back and forth, and I spent a lot of time as a child listening to the grownups talkthe ever-circling patterns of reminding that carried their thoughts from the present to the past. Some stories were repeated many times; because there was much shared knowledge, nobody would have thought of objecting to the retelling of a well-known story. This repetition of what was known in common, I think, was a sort of ritualization of the familys awareness of itself as a unit holding together through time. Among these stories there were a good many memories of slavery, casually told and heard, usually without comment beyond the facts of the narrative. What interests me about them now is that they were not forgotten, and that they were remembered and retold casually. For years that was the way I knew themcasually. They interested me, as the other stories did, because of the sense of the past I got from them. But the moral strain in them never reached me until some years after I had become a man. There is a peculiar tension in the casualness of this hereditary knowledge of hereditary evil; once it begins to be released, once you begin to awaken to the realities of what you know, you are subject to staggering recognitions of your complicity in history and in the events of your own life. The truth keeps leaping on you from behind. For me, that my people had owned slaves once seemed merely a curious fact. Later, I think, I took it to prove that I was somehow special, being thus associated with a historical scandal. It took me a long time, and in fact a good deal of effort, to finally realize that in owning slaves my ancestors assumed limitations and implicated themselves in troubles that have lived on to afflict meand I still bear that knowledge with a sort of astonishment.

The most troubling of the stories I remember hearing is about the sale of a slave. It is not the sort of story that a family could remember gladly; mine has remembered it, I think, because it is too painful to forget. My great-grandfather, John Johnson Berry, once owned a slave who was a mean nigger, too defiant and rebellious to do anything with. And writing that down, I sense as I never have before the innate violence of the slave system, and the innate flaw of the slavery myth. For if there was any kindness in slavery it was dependent on the docility of the slaves; any slave who was unwilling to be a slave broke through the myth of paternalism and benevolence, and brought down on himself the violence inherent in the system. A slave was obviously not a neighbor whom one could either associate with or ignore; so long as he remained docile (and indispensable) he was, as the myth would have it, a sort of stepchild whom the white master fed and clothed, and ruled and used. But a slave who was rebellious and mean obviously had to be dealt with, and the method of dealing with him had to be violent: the master had either to answer the slaves violence with greater violence of his own, or to invoke the institutional violence of slavery, selling the slave to someone more able or willing than himself to enact the necessary cruelty. My great-grandfather was evidently a rather mild and gentle man by nature, and he lived in a country of relatively small farms where domestic violence would have been very noticeable and disruptive. Unwilling for these reasons to commit personal violence against his slave, he was forced to accept the institutional violence as a sort of refuge. He sold the slave to a local slave buyer by the name of Bart Jenkins.