Contents

Guide

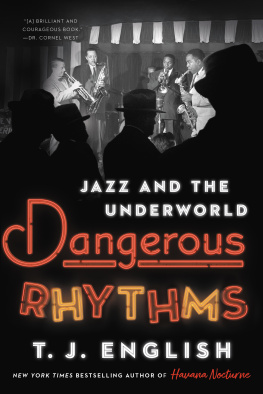

DANGEROUS RHYTHMS . Copyright 2022 by T. J. English. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

FIRST EDITION

Cover design by Julianna Lee

Cover photographs: Max Kaminsky, Lester Young, Hot Lips Page, and Charlie Parker (left to right) performing at Birdland Bettmann/Getty Images; Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: English, T. J., 1957- author.

Title: Dangerous rhythms : jazz and the underworld / T. J. English.

Description: First edition. | New York : William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: From T.J. English, the New York Times bestselling author of Havana Nocturne, comes the epic, scintillating narrative of the interconnected worlds of jazz and organized crime in 20th century AmericaProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021060831 (print) | LCCN 2021060832 (ebook) | ISBN 9780063031418 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780063031425 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9780063031432 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: JazzSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | JazzHistory and criticism. | Music and crime. | Organized crimeUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC ML3918.J39 E65 2022 (print) | LCC ML3918.J39 (ebook) | DDC 306.4/84250973dc23/eng/20220315

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021060831

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021060832

Digital Edition AUGUST 2022 ISBN: 978-0-06-303143-2

Version 07062022bcm

Print ISBN: 978-0-06-303141-8

To all the musicians and jazz club impresarios

who kept the music alive during

the Great Pandemic of 202022.

In the primitive world, where people live closer to the earth and much nearer to the stars, every inner and outer act combines to form the single harmony, life. Not just the tribal lore then, but every movement of life becomes a part of their education. They do not, as many civilized people do, neglect the truth of the physical for the sake of the mind... The earth is right under their feet. The stars are never far away. The strength of the surest dream is the strength of the primitive world.

Langston Hughes, The Big Sea

Its got guts and it dont make you slobber.

a Chicago gangster explaining his love for jazz

Contents

There is a reason that Strange Fruit still stands as the seminal jazz song. Written by Abel Meeropol in 1937 and sung so memorably by Billie Holiday two years later, it beckons from the great beyond, elliptical and haunting. The song is both a ballad and a primal scream, an aching tone poem that carries with it the deep, heart-wrenching emotionalism of the blues, as well as the lucid, steely observationalism of someone who has been a witness to history. In form and content, it is a brutal diagnosis of the human condition in B-flat minor. That this song speaks for jazz at the core of its being is no accident. It is a circumstance so sacred that any discerning listener of Strange Fruit can hearand feelthe alchemy of lyrics, poetry, melody, and soulfulness that, through the artistry of Lady Day, rankled the conscience of America and set a new course for what has become this countrys most durable art form.

Strange Fruit finds its power in the perverse metaphoric imagery of Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze, strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees... Blood on the leaves, blood at the root.

It is a song about lynching.

And it is a song about America.

It is generally agreed that jazz as a new musical art form began to take shape in the early years of the twentieth century. It is not generally commented upon that jazz, in its origins, was a response to the horror and reality of lynching in America. But consider this: From 1882 to 1912, in the thirty years leading up to the onset of jazz, there were 2,329 instances of lynching of Black people in the United States (according to statistics of the Tuskegee Institute). Many believe this number is low, given that the documentation of lynching was suppressed for generations.

During this period, a reign of terror was unleashed upon African Americans. Each act of lynching was designed to have a ripple effect beyond the individual person whose life was taken. The perpetrators meant to send a message to the entire Black community. Ritualistic, methodical, perverse in naturethe killings were designed to extinguish both body and soul.

They were also designed to traumatize the living by sending a chill through the hearts of Negroes that would be internalized and passed down from generation to generation.

Very few Black families in the American South and beyond were not touched in some way by lynching. If it was not a family member, a relative, or a friend who was murdered, it was someone in the community who was perhaps only a few steps removed. Of those many instances of lynching during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, each act contributed to the overall effect of violent intimidation. Sometimes the process involved male genitals being severed and ears cut off and kept as trophies or mementos. Sometimes the killings were secretive or clandestine, but just as often they were conducted as public spectacles. Women and children gathered to observe the torture and hanging of a victim. The atmosphere at these events was festive, convivial, with white people gathering to affirm that despite the eradication of slavery as a legal institution, the dictates of white supremacy in the antebellum South would live on.

The fact that these spectacles were sometimes carried out with the acquiescence of legal authoritiespoliticians, local lawmen, Christian church leadersundermined the confidence of Negroes in their own country. Lynching was designed to enforce the view that for Black folks in America, a sense of inferiority and terror was their rightful inheritance.

For the would-be inventors of jazz, this was the contemporary state of affairs. Black folks who sought to make music, to partake in a tradition that had flourished on the plantations and elsewhere for generations, did so with the knowledge that they were creating their sounds within a social context that was malignant and hostile.

The instruments were not new. String instruments, various types of horns, the piano, and drums had been around for decades or, in some cases, centuries. But what these early musicians were attempting to do with these instruments was almost beyond calculation.

It is difficultperhaps even impossiblefor people today to grasp the full immensity of what was taking place. The early formations of jazzthe rhythm patterns, melodic phrasings, and occasionally aggressive syncopationwere revolutionary. It has been commented upon that the creation of jazz was an attempt to codify an entirely new language. But it was more than that: Jazz was an attempt to rearrange the molecular structure of the universe, to obliterate recent history and replace it with expressions of joy, inventiveness, and grace. This new music was nothing less than an attempt to achieve salvation through the tonal reordering of time and space. The music was an affirmation of the human spirit, a declaration of the present tense. As the writer Stanley Crouch wrote, Nothing says I want to live as much as jazz.