Contents

Guide

Page List

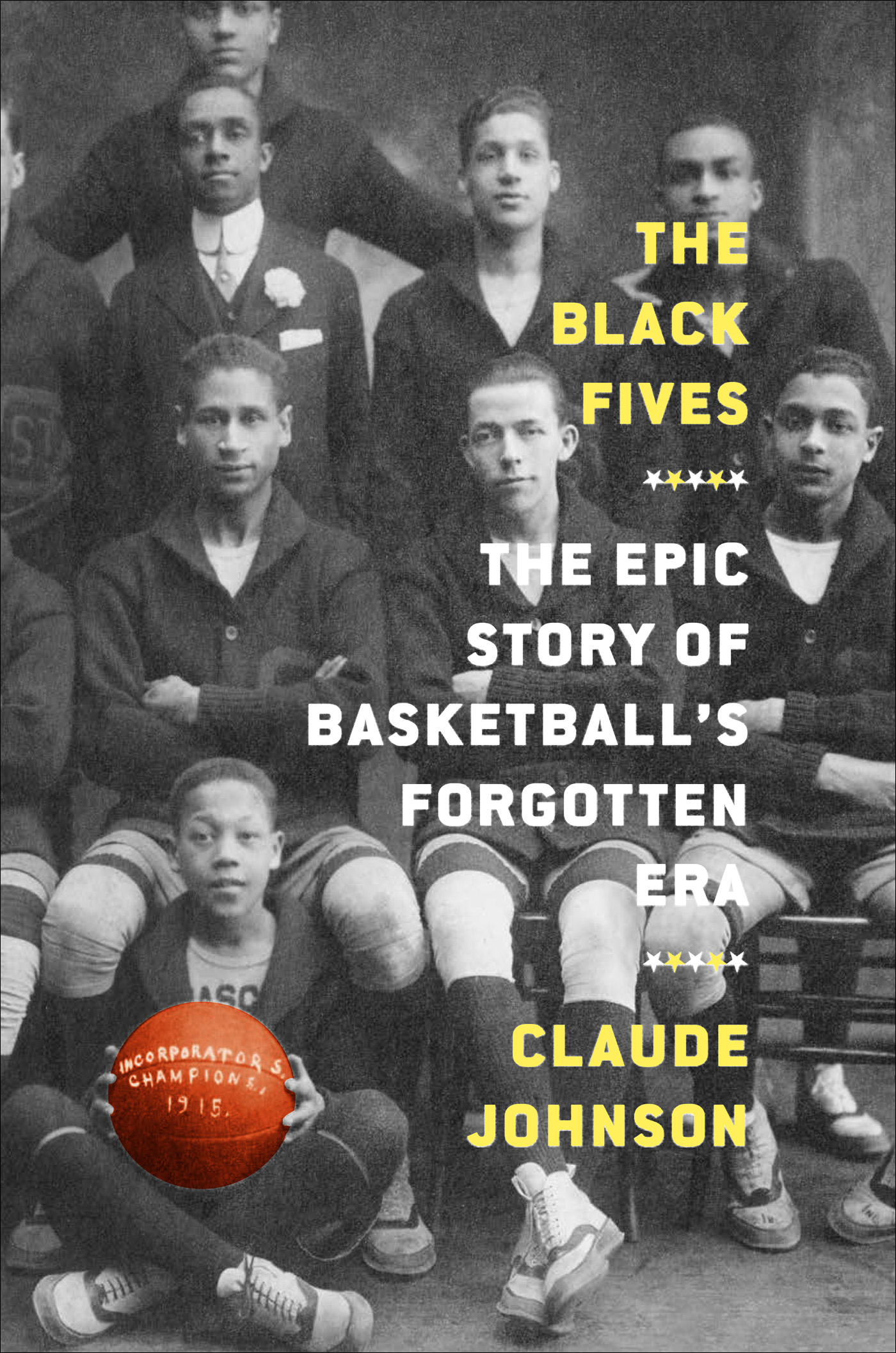

Copyright 2021 Claude Johnson

Cover 2021 Abrams

Published in 2021 by Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021933480

ISBN: 978-1-4197-4436-5

eISBN: 978-1-68335-908-1

Abrams books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams Press is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

| ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com |

For

my Mama, who had a book in her

my Dad, who wanted to finish his book

my Siblings, who have always been there

my Sons, who inspire me to keep at it and keep at it

my 5 x 7s

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

AN UNMARKED GRAVE

On a Narrow Patch of grass and dirt in Tier 4 of the Villa Palmeras section at the back of Rosedale Cemetery in Linden, New Jersey, there is a flat chunk of rocky cement with 47 scrawled on it, as if written by hand using a crooked stick while the concrete was still wet. This is Plot Number 47, an unmarked grave. It contains the remains of William Anthony Will Madden. He died at age eighty-nine on Tuesday, February 20, 1973, in the Greenwich Village section of New York City, alone, with no family or friends.

Rosedale is an old burial ground that occupies ninety acres of flatland along the New Jersey Turnpike, about thirteen miles southwest of Manhattan. Developed in 1900, it is one of the longest-running businesses in Linden, a town best known for its dozens of gigantic, white, million-gallon petroleum storage tanks, familiar to drivers using Interstate 95 in that section. Hiding behind those vast containers is Rosedale. Though its vintage buildings and tree-lined paths hint at better days gone by, no one famous was ever buried there.

In the early 1970s, New York City ran out of graveyard space and, as a cost-saving move due to financial troubles, began sending its unclaimed dead to various cemeteries in New Jersey. These unaccountable goners were people with no next of kin and nobody else who had known them. Rosedale was one of those sites and the Villa Palmeras section there became filled with the untitled graves of those voiceless souls.

By law, investigation of their cases had to be assigned to the citys Office of the Public Administrator. Thats what happened to Will, after whose death the PAs office searched his last known residence for personal belongings that might offer clues about next of kin or acquaintances. That came up empty. No surviving spouse, children, grandchildren, siblings, cousins, or other relatives could be traced. No friends, acquaintances, or former coworkers stepped forward. He had left behind no will and no instructions for what to do with his body or his property. Its efforts having reached a dead end, the PAs office issued a final statement: Nothing was found among decedents effects which would assist your petitioner in who the distributees of decedent were or where they might be located.

According to the citys legal terminology, Will had died intestate, not only without a will but also without anyone to speak on his behalf. Following protocol, the handling of his affairs and burial arrangements were sent to the Surrogates Court, whose responsibilities included forwarding his mail, paying his bills, settling his debts, and closing out his accounts. The court selected the Gannon Funeral Home in Manhattan from New York Citys list of approved funerary service providers for such cases, which were usually low-budget.

Even though Gannon prepared Wills body, there was no funeral service. No mourners gathered, no final farewells. The corpse was transported to Rosedale, but the cemeterys chapel went unused, and instead of a casket, he got a plain pine coffin.

Will was anonymous on the day of his interment, February 26, 1973. No obituary was published in any newspaper. No headstone was placed, then or later, which meant no epitaph would list his lifes accomplishments. Just that jagged edged 47 slab to mark the spot where he was put into the ground. Only the gravediggers on duty were present at Wills burial. The nearby mound of displaced soil was twice as high as usual because the hole was double depth. To save money, graves for the citys intestate clients were dug deep enough for two coffins, stacked one on top of the other. The box containing Wills remains went in first. Instead of resting six feet under, his coffin was placed twelve feet down, like being stuck at the bottom of a bunk bed. Forever.

Any last words spoken at the burial were purely symbolic. Even if we just say, We consign the remains to the earth, at least we give them a reasonably dignified sendoff and show respect, said Wilson Beebe, executive director of the New Jersey State Funeral Directors Association, in a 1995 interview about the states handling of all those unclaimed bodies.

The pile of dirt next to the grave was moved back into the open hole, one shovelful at a time. William Anthony Madden was the former king of the basket ball world and Beau Brummel of New York City, but as the pine box containing his remains gradually became covered up, the pioneering African American sports history to which he had contributed was buried with him, and this case of an elderly man from Greenwich Village who had died alone was officially closed. But the soul of the dearly departed had far to go before it could rest in peace. That history was Wills story, and it had never been unburied or fully told. Until now.

CHAPTER 2

SURVIVAL

Will Madden, the first rightful king of Black basketball in America, ascended to that throne because he came from a family of survivors. This was established during the Civil War, on the evening of Tuesday, July 14, 1863, in New York City, as bloodthirsty mobs of enraged working-class Whites roamed Midtown Manhattan armed with clubs, pitchforks, iron bars, swords, and many with guns and pistols, looking for any African Americans they could find. Nothing was spared. The Colored Orphan Asylum at Forty-Fourth Street and Fifth Avenue, home to more than two hundred disadvantaged Black children, had been burned to the ground. Horses pulling streetcars had been shot to death and the cars smashed to pieces. The homes of prominent abolitionists were being looted and destroyed. Railroad tracks had been torn up and telegraph wires cut. Dozens of public buildings, including churches, were ransacked and torched. Even the house of the New York City mayor, George Opdyke, was raided and set on fire. It was mayhem.

Ever since President Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, the citys poorest Whites feared that freed slaves would migrate to Manhattan and steal their jobs. Then in March, Congress passed the Enrollment Act, which made all able-bodied adult males immediately eligible to be drafted into the Union Army. This reality sank in when the names of New York City draftees were published leading up to Draft Week. Making matters worse was that under the Enrollment Act, any wealthy man could escape the draft by paying a $300 fee (the equivalent of more than $6,500 today). The rioters specifically targeted neighborhoods where numerous mixed-race families lived.