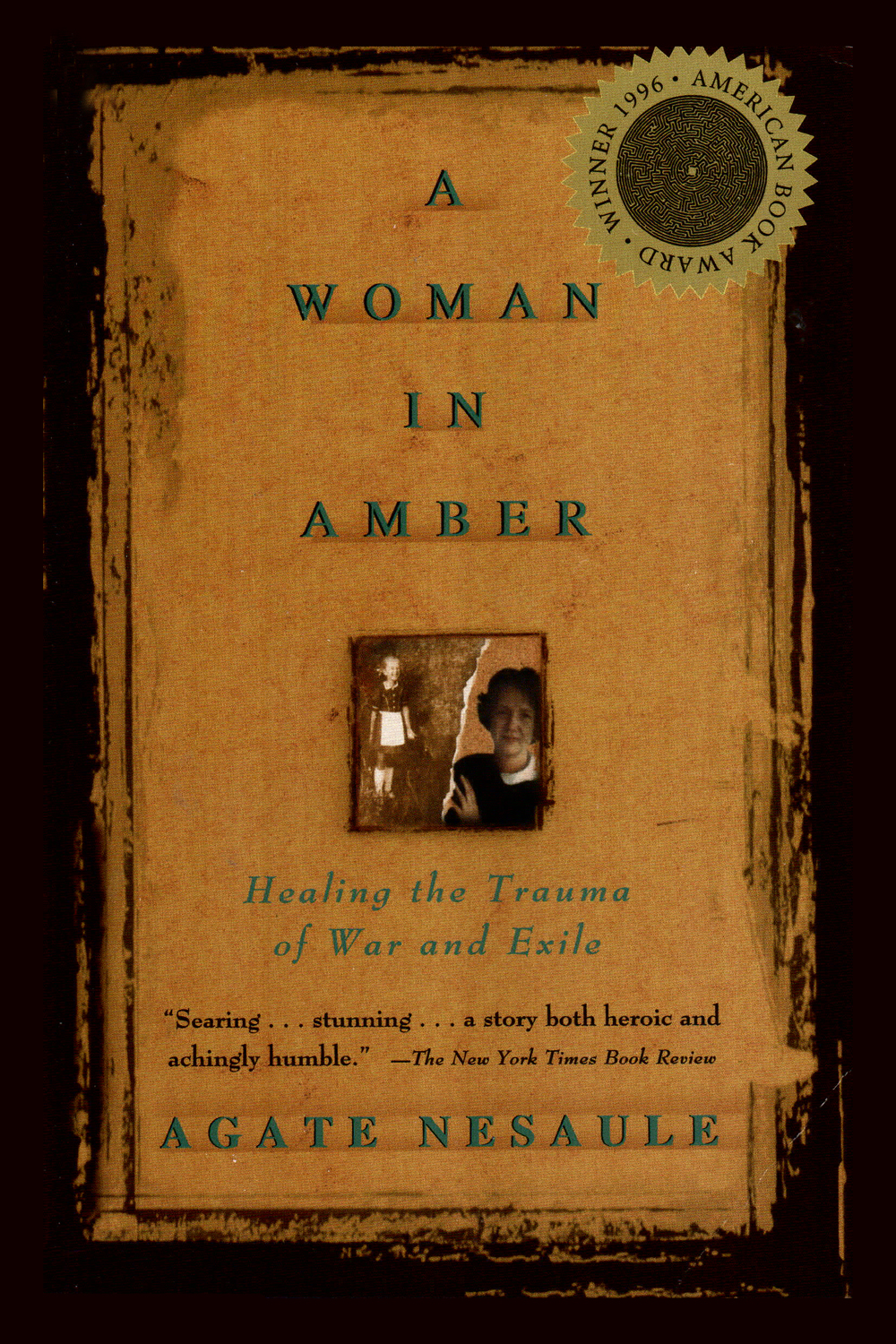

Praise for A Woman in Amber

This book, about the sufferings of civilians during the Second World War, is unlike most war books, because it deals with the long-term effects of war, and this makes it relevant now with more and more people in the world hurt by war. People who become disquieted about how much we are manipulated by experiences we might not even remember will find this perceptive book helpful. In using her memories in an effort of self-healing the author will show them the way. This is a powerful anti-war book. It is also a hopeful one... I whole-heartedly recommend it.

Doris Lessing

A brave and subtle confrontation with childhood memories of extreme horror. Agate Nesaule shows us, in disturbing but illuminating detail, how violence and cruelty register on the psyche from without, to haunt it later painfully from within. This beautifully written book makes us reckon anew with the deep costs of war, and reassures us that hope can be wrested from great suffering.

Eva Hoffman, author of Lost in Translation

Professor Nesaules story is so honestly and beautifully told that it rises above whatever lessons may be drawn from it: it is her story, her familys, and that of other Latvians, and to read it is to enlarge ones own experience.

Garrison Keillor

This rich, complex memoir is about war and its endless aftermath, about memory, denial, the breaking of taboos and the difficulty women and people from small nations encounter in taking themselves seriously... For those of us currently outside the war zone... she wrenches us out of our shamed TV-viewer passivity... A remarkable book.

Newsday

Mothers rule our destiny and this is true whether we live relatively peaceful lives or are plunged into war. Mother as archetype is the theme of this moving story.

Edna OBrien

Like all the best modern memoirs, A Woman in Amber belongs to the quest literature of our times... It draws the reader forward with the suspense of a novel, a tale told in the unmistakable voice of one searching urgently for integrity as if it were a cure. And in this memoir the cure is found.

Patricia Hampl, The New York Times Book Review

Copyright 1995 by AGATE NESAULE

All rights reserved.

Published by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Chapter 7, entitled Mothers and Daughters, was published in a slightly

different form in Northwest Review.

The excerpt from A Rose in the Heart of New York from A Fanatic Heart, copyright 1984 by Edna OBrien, is reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc. The excerpt from How to Tell a True War Story from The Things They Carried, copyright 1990 by Tim OBrien, is reprinted by permission of Houghton

Mifflin Co./Seymour Lawrence. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nesaule, Agate.

A woman in amber: healing the trauma of war and exile/Agate Nesaule.

ISBN 978-1-56947-046-6

eISBN 978-1-61695-601-1

1. Nesaule, Agate. 2. Latvian AmericansBiography.

3. Latvian AmericansCultural Assimilation. 4. Indianapolis (Ind.)Biography. 5. Madison (Wis.)Biography. 6. RefugeesUnited StatesBiography. 7. World War, 1939-1945Refugees. I. Title.

E184.L4N47 1995

940.53159092dc20

[B] 95-18907

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

With love and gratitude to the two

who helped me tell this story:

Ingeborg Casey,

who taught me that

the past is meaningful,

and John Durand,

who brought love, happiness

and peace to the present

Her mother was the cup, the cupboard, the sideboard with all the things in it, the tabernacle with God in it, the lake with the legends in it, the bog with the wishing wells in it, the sea with the oysters and the corpses in it ...

Edna OBrien,

A Rose in the Heart of New York,

A Fanatic Heart

War has the feelthe spiritual textureof a great ghostly fog, thick and permanent. There is no clarity. Everything swirls... The vapors suck you in. You cant tell where you are, or why youre there, and the only certainty is overwhelming ambiguity. In war you lose your sense of the definite, hence your sense of truth itself, and therefore its safe to say that in a true war story nothing is ever absolutely true.

Tim OBrien,

How to Tell a True War Story,

The Things They Carried

Authors Note

I have uncertainties about this story. I was only seven when some of the events took place, and there is so much that I have forgotten or I never knew or understood. But I have not been able to compare my recollections with others. No one in my family wants to talk about the war: they may have silent images, but they tell no stories. And no matter how hard I try, I cannot force myself to do research. I can only bear to read novels, as if they were safer, not factual accounts of the period.

I know that memory itself is unreliable: it works by selecting, disguising, distorting. Others would recall these events differently. I cannot guarantee historical accuracy; I can only tell what I remember. I have had to speculate and guess, even to invent in order to give the story coherence and shape. I have also changed some names and identifying details to protect the privacy of others.

The matter of inventing requires a special note. All memories, but especially traumatic ones, are originally wordless. Putting them into words inevitably transforms them (Judith Lewis Herman, Trauma and Recovery, Basic Books, 1992). One verbal form is not necessarily truer than another, yet many people naively prefer narration and summary over dramatization and dialogue. I have chosen to show the people from my past in action and I have allowed them to speak because that is how I see and hear them. Ultimately all memoirs are attempts at inventing the truth (William Zinsser, Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, Houghton Mifflin, 1987). Yet they also test the writers integrity and require constant striving for fairness and authenticity .

Why tell this story now, so many years after World War II? In all wars the shelling eventually stops, most wounds heal, memories fade. But wartime terror is only the beginning of stories. The small boy with arms raised in the face of guns, the girl forced to witness rape, the emaciated children begging for food, if they survive, all have to learn how to live with their terrible knowledge. For more than forty years, my own life was constricted by shame, anger and guilt. I was saved by the stories of others, by therapy, dreams and love. My story shows healing is possible.

Wars are never-ending, and so are their stories. I pray for an end to war, and I fervently hope for greater understanding for all its victims. I want tenderness for them long after atrocities end.

Part I

Talking in Bed

W e are talking in bed, friends again instead of lovers. Apricot-colored fern fronds wave against the pearl gray background of my flannel sheets. Both of us are surprised to hear thunder, thunder in February, in Wisconsin, over frozen ground and dirty snow. My hand rests lightly on his gray hair, our legs are still entwined. Soon we will turn away from each other, but our backs will touch, close enough to stay warm. We will dream different dreams. He will walk in the Sangre de Cristo mountains of New Mexico or drive over a wooded Wisconsin road towards Birch Island Lake. I will carry a baby away from a burning Latvian village, evade Nazi guards, catch the last train. When we dream about being seven, we speak different languages.