This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1960 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

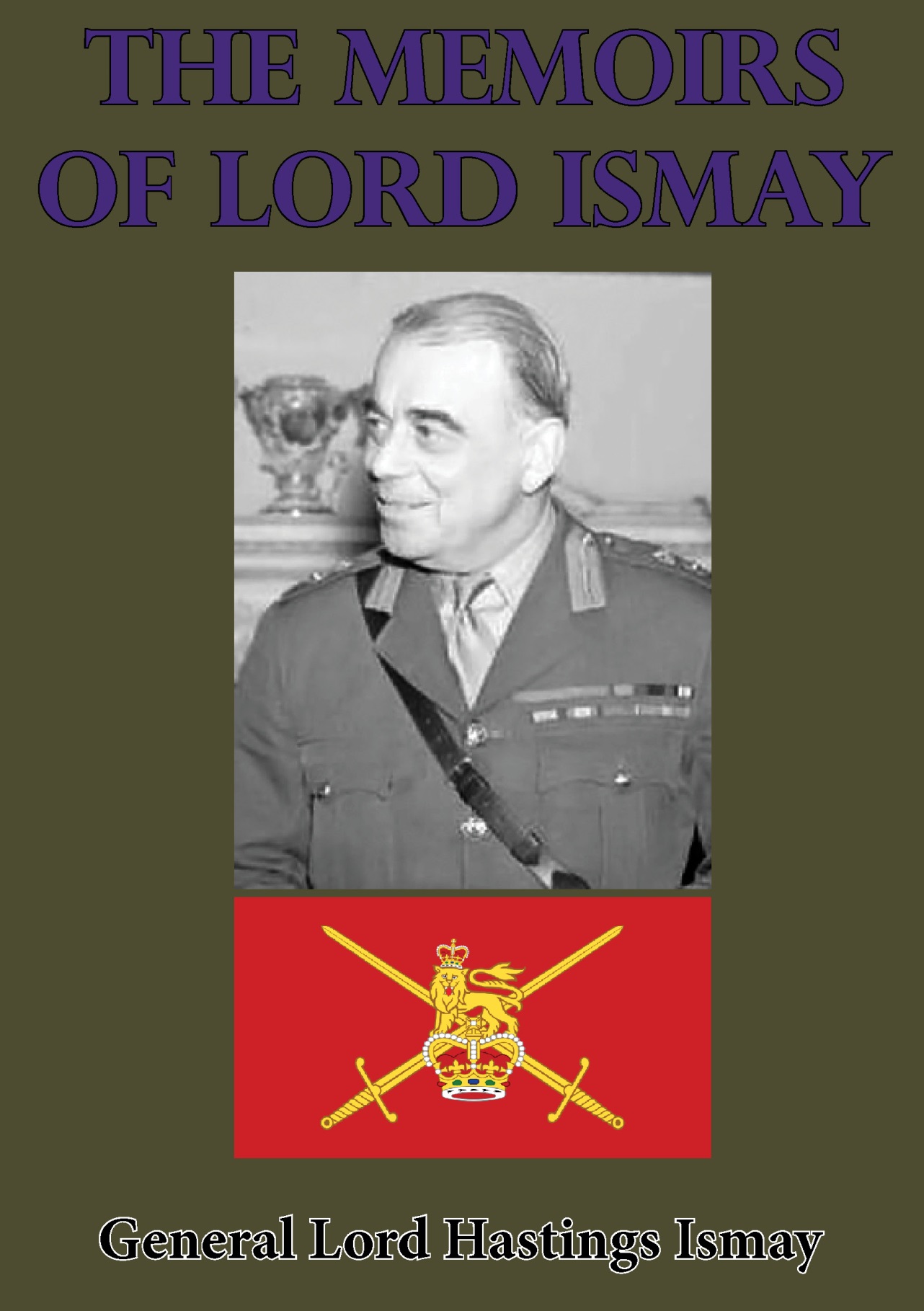

THE

MEMOIRS

OF

GENERAL LORD ISMAY

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

DEDICATION

FOR DARRY

Giving thanks always for all things

Epistle of Saint Paul to the Ephesians 5:29

MAPS AND DIAGRAMS

The North-West Frontier of India

British Somaliland

Committee of Imperial Defence 1926

Committee of Imperial Defence 1936

Defence Machinery 1942

India before Partition

India after Partition

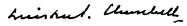

LETTER FROM SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL

28, Hyde Park Gate

LONDON, S.W. 7.

I am very glad that Lord Ismays Memoirs should now be published. For many years he has held positions of high importance at the centre of our affairs, and he has an intimate and commanding knowledge of the great events of the war.

In the first volume of my Memoirs of the Second World War I wrote, I had known Ismay for many years, but now for the first time we became hand in glove and much more, and I am glad again to record my tribute to the signal services which Lord Ismay has rendered to our country, and to the free world, in peace and war.

April, 1960

PREFACE

When Mr. Churchill became Prime Minister on 10 May 1940, he assumed, with the Kings approval, the additional appointment of Minister of Defence, and it was my incredibly good fortune to serve as his Chief of Staff in that capacity until the fall of his Administration on 26 August 1945. I had always intended to write my account of those crucial years, a background to a pen portrait of Churchill at war, but it was not until 1957 that my retirement from the public service gave me the necessary leisure for the stewardship of my own affairs. By the end of the following year I had made considerable progress, but I was advised on all sides that my story would be incomplete unless I included an account not only of the steps which led an officer of Indian Cavalry to the fountain-head of national and Imperial defence in London, but also of my experiences as Chief of Staff to the last Viceroy of India, the Earl Mountbatten of Burma, and as Secretary-General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. As a result these memoirs are a good deal more egotistical, cover a much larger canvas, and have taken considerably longer to finish than I had hoped, A great many of my personal friends have helped me with advice and encouragement, and I ask them to absolve me from the charge of ingratitude for not mentioning them by name.

PART ONE APPRENTICESHIP

CHAPTER I Subaltern in India 1902-1914

On a July afternoon in 1902, a diminutive Carthusian of fifteen summers was practising at the cricket nets, when somebody shouted out that the results of the examination for senior scholarships had been posted up in the cloisters. He went there as fast as decency permitted it would have been bad form to appear excited only to find that the name H. L. Ismay did not figure in the list. It was a bitter disappointment, because I had been consistently above at least four of the successful scholars for the whole of the past year; but I swallowed the lump in my throat and returned to the cricket nets feigning nonchalance. I did not realise at the time that my failure was a blessing in disguise.

When I was alone in my cubicle that night, I may or may not have shed a few tears, but I certainly did a lot of thinking. Ever since the South African War, I had had a sneaking desire to be a cavalry soldier; but my parents wanted me to go to Cambridge and try for the Civil Service. Now that I had proved such a duffer at examinations, my chances of passing were remote. If I were to fail, what could I do for a living? I would be too old to qualify for any other profession, and in those days commerce was not considered suitable employment for a gentleman.

The more I thought about it, the more sure I was that I wanted to have a try for the Army as soon as I was old enough. But there was plenty of time before a final decision need be made, and it was over a year before I unburdened myself to my parents. By an unfortunate coincidence, a letter from my housemaster reached them at almost the same time. I have never got over your boy missing a scholarship, he wrote. It is one of those exasperating miscarriages of examinations which happen often enough, but rarely in a form which can be estimated so exactly. This high assessment of my abilities might have ruined my plans, but my parents, bless them, let me have my way. My father was particularly upset at the idea of my joining the Indian Cavalry, and never tired of telling the story about the cavalry officer who was so stupid that even his brother officers noticed it. I wish that he could have lived long enough to know that it did not turn out to be so much of a dead end as he had feared.

In the summer of 1904, I passed the necessary examination without too much difficulty, and in the autumn I entered the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. The year as a gentleman cadet passed pleasantly enough. It toughened me physically, and I learned to drill like a guardsman, shoot with rifle and revolver, dig trenches, ride, signal, draw maps, do gymnastics and wear my clothes correctly. I also learned a smattering of military tactics, history and engineering. But so far as I remember, man-management and the art of command found no place in the syllabus. Sandhurst never meant nearly so much to me as Charterhouse had done. The course lasted only one year, and there were few opportunities for making new friends outside ones own term in ones own company. Many of my contemporaries were destined to be killed or crippled in the First World War and, partly for that reason, an unusually high proportion of them went to the top of the military ladder. Notable among these were Field Marshal Lord Gort, Marshal of the Royal Air Force Lord Newall, Generals Platt, Gifford, Riddell-Webster, Franklin and Heath, and Air Chief Marshal Ludlow-Hewitt.

In those days there was keen competition for the Indian Army, and it was necessary to pass out in the first thirty or so to be sure of a vacancy. I had evidently improved at examinations, as I took fourth place and was gazetted a Second Lieutenant in His Majestys Land Forces on 5 August 1905. I was under eighteen-and-a-half years old and the smallest officer in the Army. Fortunately for myself and my tailor I grew six inches in the next two years.

Next page