IMAGES

of America

BERKLEY

In 1960, the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) and the American Legion held a contest to design a new flag for Berkley. Berkley High School senior Gary Ostendorf won, and his entry continues to serve as the citys emblem, appearing on city documents, signage, and the flag. The colors are satellite blue on white for space-age optimism. The sphere represents the world, while the oak leaves symbolize Oakland County. The church, book, liberty bell, and family stand for important aspects of Berkley life.

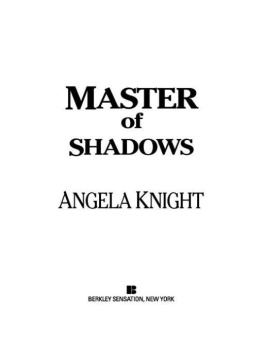

ON THE COVER: Members of the Berkley Fire Department stand next to their 1953 American LaFrance. Berkley City Hall housed the fire station and the police on the first floor. The second floor contained other city offices, including the first library. The small white house to the left of city hall contained the finance department, which was relocated to city hall in 1989, when police and fire operations were moved into the new Public Safety Building.

IMAGES

of America

BERKLEY

James Jeffrey Tong, Dr. Susan Richardson,

and Hon. Steve Baker

Copyright 2013 by James Jeffrey Tong, Dr. Susan Richardson, and Hon. Steve Baker

ISBN 978-0-7385-9975-5

Ebook ISBN 9781439642276

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013931090

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

The authors dedicate this book to their family and friends for their tremendous love and support, especially (Jeff) Emily and James Vickey; (Sue) Mark, Emma, and Eric Richardson; and (Steve) Nicole Artanowicz, Suzy Marin, and Christine Baker.

CONTENTS

The authors thank the large number of people who shared their time, photographs, knowledge, and enthusiasm with us. This book would not have been possible without their support and the patience of our families.

We most especially recognize the major role played by three women who have worked for years to collect and preserve Berkleys history. The late Shirley McLellan was the pioneer in preserving and writing about our past. As the Berkley reporter for the Daily Tribune for many years, she wrote extensively about our history. Much of the museums collection was due to her work as the first chairperson of the Berkley Historical Committee.

Carol Ring was the first vice chairperson of the Berkley Historical Committee and later replaced Shirley as chair; she continues to serve on the committee. Maybelle Fraser was Berkleys first female mayor and a major researcher into our past. These two women have devoted years to collecting and sharing information about the citys past, and they spent hours with us looking at photographs and answering our questions. They have been extremely patient and gracious, and we sincerely thank them.

In addition, Mary Hughes, former Berkley city clerk, compiled a brief history of the city in a booklet distributed during the celebration of Berkleys 75th anniversary in 2007. Her collection of photographs and historical records served as inspiration for this project.

We also thank the current and recent members of the Berkley Historical Committee for their dedication and countless hours of volunteering to preserving Berkley history: Bill Ackerman, Elaine Andrade, Karen Brocklehurst, Shirley Hansen, Janice Lovchuk, Waneda Mathis, Mary-Catherine Mueller, Danielle Ozanich, Carol Ring, and Neil Ring.

Finally, we are grateful for the following who shared information and photographs with us: J.S. Brooks, Mike Cotroneio, Robert Cook, Daniel Darga, Jerry Durst, Pat Fox, Yvonne Fuller, Heather Hamlin, Shirley Hansen, Judy Harnois, Harry Hartfield, Rob Henry, Mark Keegan, William Krieger, Mike Kurta, Nancy Line, Kyle Matthews, R. Murphy, Cheryl Printz, Robert Roberts, Donna Sayers, Kathy Schmeling, Tim Toggweiler, Marcia Tong, and Celia Morse, director of the Berkley Public Library, and her staff. Please forgive us for any omissions, as those would be purely unintentional.

Unless otherwise noted, photographs are courtesy of the Berkley Historical Museum.

When settlers began arriving in what would become Michigan, the land where Berkley now stands was not considered suitable for habitation. The first government maps show the entire area to be one big swamp with a huge forest of maple, oak, elm, beech, and pine. The trees were so thick that the sun could not even reach the ground to dry the land, and the many brooks flowing from underground springs further contributed to the watery environment.

Even the Native Americans avoided the area. The soil was too thick and gummy for growing crops, and the deep forest prevented the growth of edible plants, which in turn reduced the amount of game for hunting.

A survey of the land ordered by the US government after the War of 1812 concluded that the swamp could not be drained, and even if it could be, the land was so poor as to discourage habitation. Settlers in Detroit avoided the area and used rivers and lakes to go around it.

However, Territorial Governor Lewis Cass decided to check out the area himself in 1817 and told Congress that the land should be sold. In 1818, the government started selling land in what would become Berkley for $1.25 an acre. Settlers from the East, lured by the promise of cheap land, began to arrive.

These early arrivals started draining swamps and clearing the land. They had to contend with malaria, cholera, and ague. These thrifty, industrious, and religious settlers included Lyman Blackmon, who gave a half acre of his land to be used as a school in 1834 (it was used until 1901).

By 1832, there was regular travel between Detroit and Pontiac that passed through Berkley. The trail people used is today known as Woodward Avenue, a major artery in the Detroit metropolitan area, but in the early 19th century the road was so muddy that coaches were constantly getting stuck and had to be pushed out.

In 1834, the Territorial Legislature of Michigan decided it had to do something to improve transportation because farmers needed more dependable means of getting their crops to market in Detroit. The legislature authorized the construction of the Detroit-Pontiac Railroad. This early rail line was primitive and even dangerous, as cinders from the engines often caused fires. But it was progress, and more and more people arrived in Berkley.

Among those who came was John Benjamin, who founded the first industry in Berkley. He began making excellent grain cradles that were sold all over the East and as far west as St. Louis. Still, settlement was painfully slow. Berkley consisted of a few scattered farms with no stores or services. Farmers went into Royal Oak or Birmingham for their daily needs.

Life changed in the early 1900s with the appearance of the automobile. When Henry Ford began producing his Tin Lizzies in nearby Highland Park, the effects were felt in Berkley. The high wages for Ford employees attracted settlers from all over America, and many found their way to Berkley. By 1915, many early Berkley residents worked in the Highland Park factory.

Next page