Contents

A Note from the Author

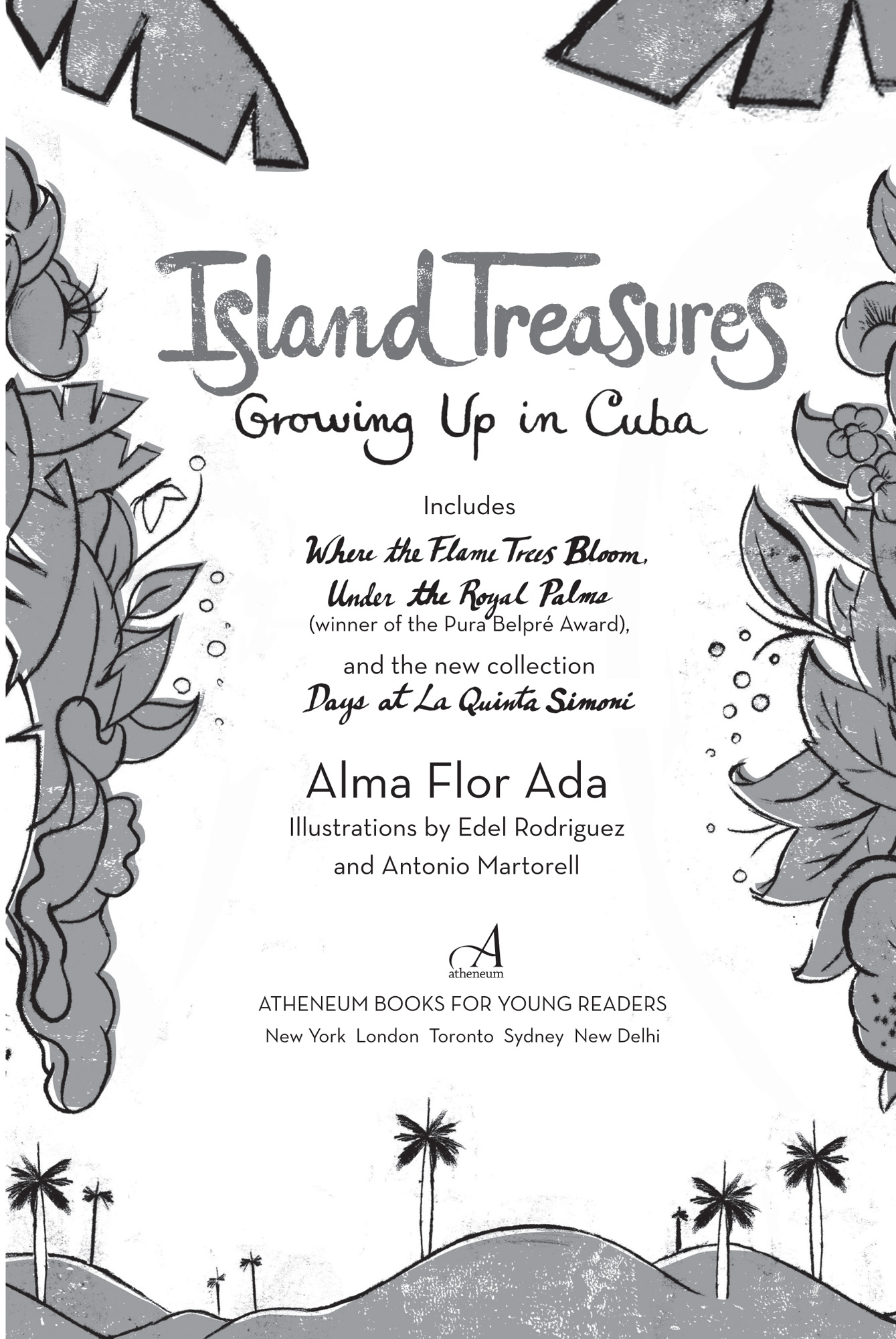

ISLAND TREASURES contains two previously published books Where the Flame Trees Bloom (1998) and Under the Royal Palms (2000)as well as Days at La Quinta Simoni, a set of stories new to this collection. All of these narratives are based on my childhood memories.

Writing about my childhood has been a way of keeping alive cherished memories and honoring the people who nourished me. Today, there is another reason I treasure these stories: the response they have received, over the last fifteen years, from readers who have found delight and inspiration in their pages.

Many of you have written to tell me that the attention these stories give to the simple details of daily life has helped you value things previously taken for granted. Others have written to say that these stories moved you to a greater appreciation of your own families. And I am delighted whenever I hear that some of you have begun to write about your own lives!

It is my hope that, through my recollections of everyday moments, new readers of all ages and from all over the planet will come to understand this unique period in Cuban lifeand to discover that each one of us has a world of stories to tell.

To Samantha Rose as your life begins to bloom

I WAS BORN IN Cuba. The largest of the islands in the Caribbean, Cuba is long and narrow. If one looks at a map of Cuba with a little bit of imagination, the island resembles a giant alligator, resting on the water. The western part of Cuba is very near Florida, while the eastern part is very close to the Dominican Republic and Haiti. In climate and natural beauty, Cuba is quite similar to Puerto Rico. In fact, Cubans and Puerto Ricans have a shared history, which is why a Puerto Rican poet once said that Cuba and Puerto Rico are two wings of one bird.

On both ends and also in the center, Cuba has high mountain ranges covered with dense tropical forests. In between these three mountainous regions are flat, fertile lands. I grew up on the eastern plains, the cattle region, on the outskirts of Camagey. Ours was a town of brick houses with tile roofs and massive old churches built of stone, which in the past served both as houses of worship and refuge for pirates. The churches high towers allowed lookouts to keep watch for cattle-thieving buccaneers.

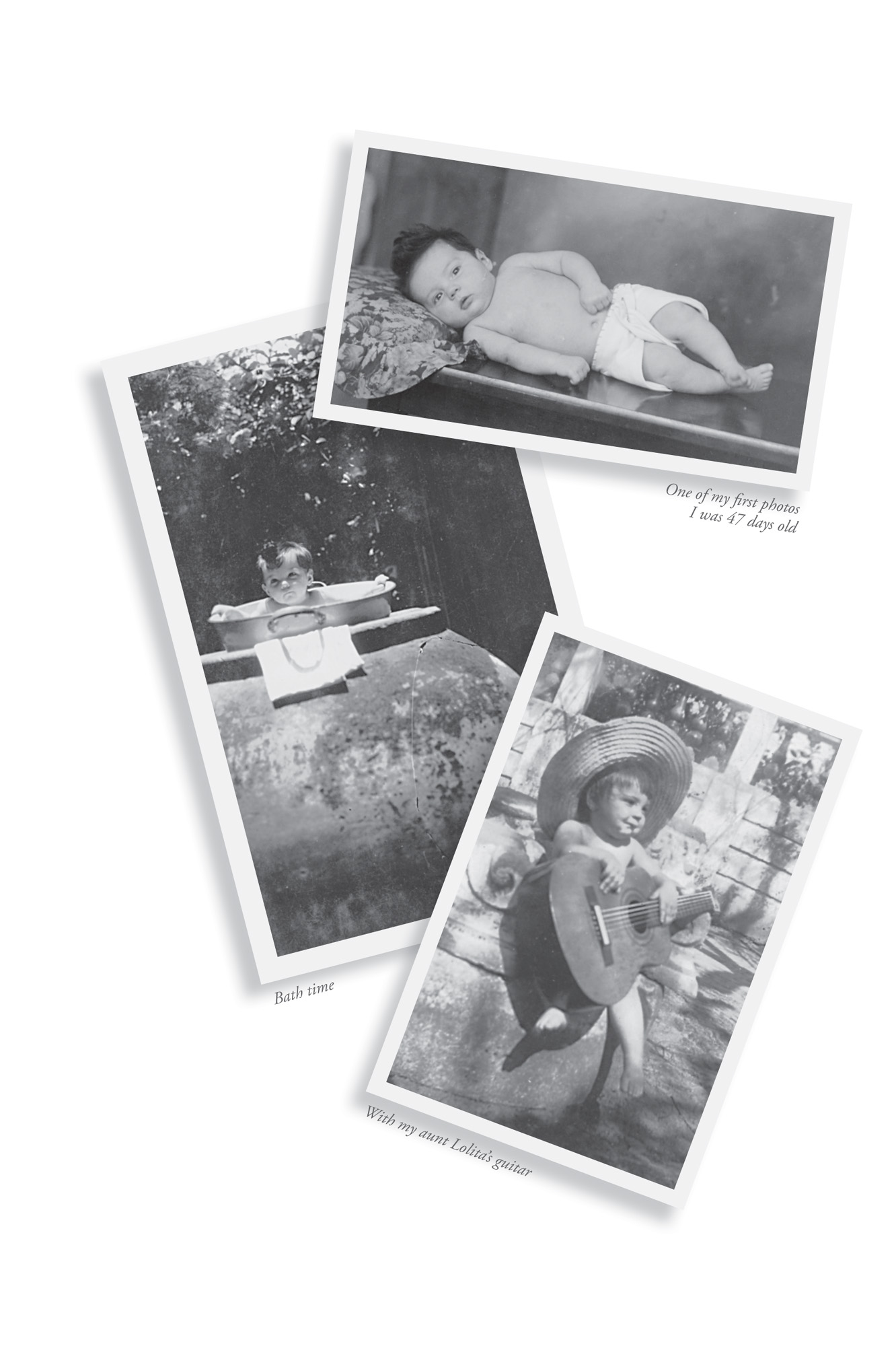

The house I was born in, La Quinta Simoni, was very large and very old. My abuelita Lola, my mothers mother, had inherited it from her father. My youngest aunt, Lolita, had been born in the house. A generation later, two of my younger cousins (Nancy and Mireyita), my sister Flor, and I were also born in the same houseright at home, not in a hospital.

Although the house was large, we were not wealthy. However, I did grow up surrounded by a wealth of family. At one time, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins all lived together under one roof. For one wonderful year, my two older cousins, Jorge and Virginita, also lived there. Yet for most of the first seven years of my childhood, I was the only child living in the house.

La Quinta Simoni also held a lot of history. It was originally built as a colonial hacienda , or ranch, by an Italian family, the Simoni. Life on their hacienda included planting crops, raising cattle, and tanning hides, as well as making bricks, tiles, and household vessels from the red clay found by the river. In those days, most of the work was done by the people the Simoni kept as slaves.

Much later, by the time I was a child, the house had grown old and weathered and the gardens overgrown. The central fountain, now dry and filled with earth, served as a planter for ferns. In the back of the house, several large rooms that had once served as dormitories for the enslaved workers were now put to other uses. A short distance away, a small brick house called el calabozo stood as a reminder of the horrible things human beings can do to one another; the iron rings on its walls had been meant to hold people in chains.

During colonial times, one of the two daughters of the Simoni family, Amalia, married Ignacio Agramonte, a Cuban patriot who fought to gain independence and freedom for all who live in Cuba. One of the first acts of the Cuban Revolution in 1868 was to free all slaves.

It was this connection with the Cuban struggle for freedom, not its earlier painful history, that made my family proud of our home. For me, the past was filled with unanswerable questions: How could anyone dare to think that a person could be owned by another? And how could we be so proud of our freedom and independence while some children still walked the streets barefoot and hungry?

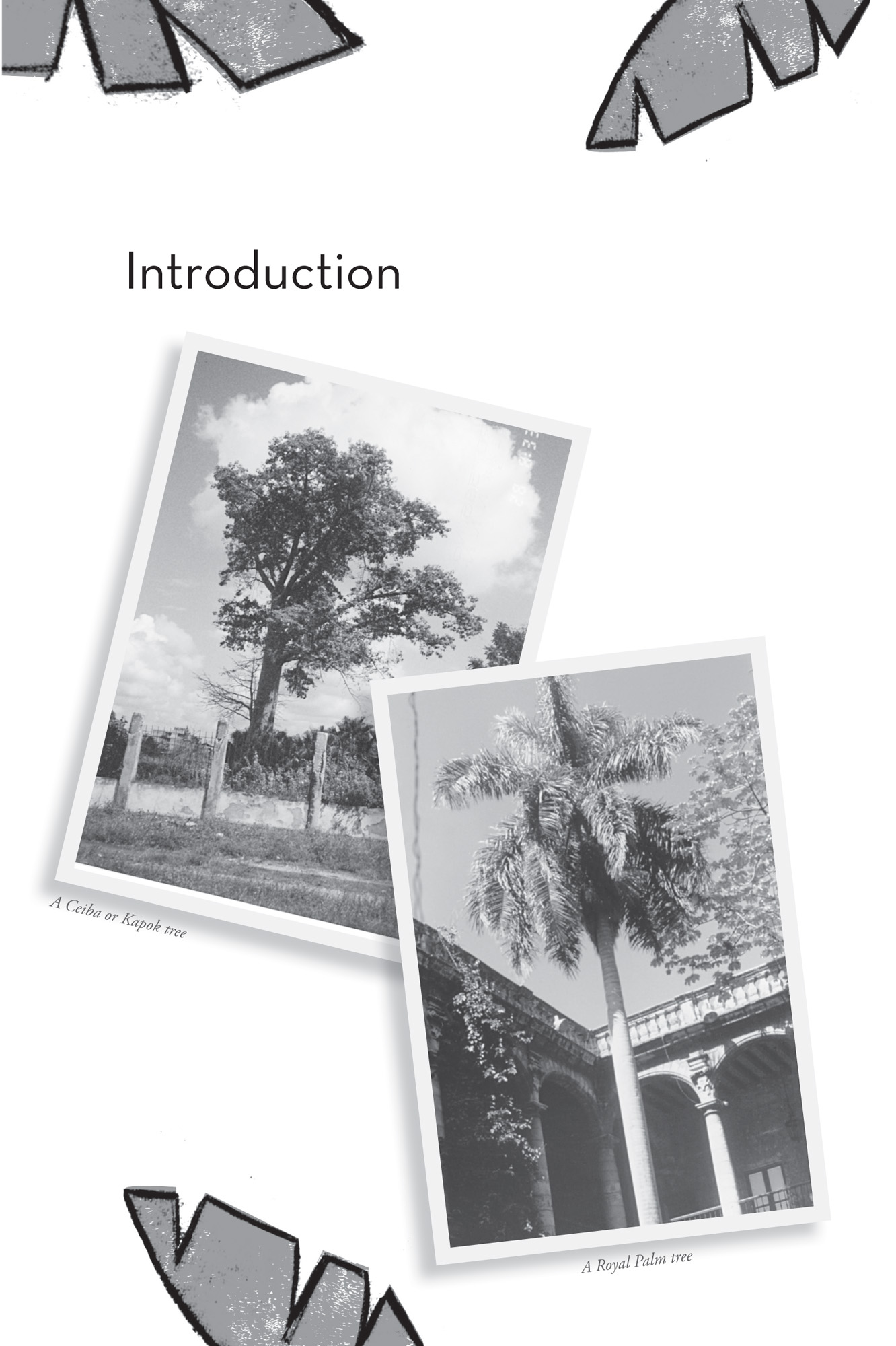

Even with these troublesome questionsbig ones for a young child to ponderthe old house remained a magical world for me. In addition to large flocks of chickens, ducks, and geese, my abuelita kept peacocks as well. The colorful birds often perched in the open dining room windows that faced out into the garden. Sometimes they would nest atop a large masonry arch, built as a small-scale replica of the French Arc de Triomphe in the long-abandoned garden by the river. Bats hid above the porch ceiling, and doves flocked on the terraces. My mother took in every stray cat that crossed her path, and the garden and courtyard were busy with lizards and snails, frogs and toads, crickets and grasshoppers. A family of hawks lived in the branches of a nearby tree. Yet even among all these living wonders, my best friends were the trees.

Large, firm, and strong, the trees offered me their friendship in many different ways. Their green canopies provided treasured shade during the heat of the day, allowing me to stay outdoors while sheltered from the tropical sun. Whether I felt lonely or joyful, they always welcomed me.

Ancient flame trees, more than a hundred years old, formed an avenue along one side of the house leading to the white arch and the river. Gnarled with age, their large roots protruded from the earth, offering me a nest where I could crawl in to feel protected and secure. Their worn, smooth roots were pleasant to the touch, and I would caress them as one might hold a dear friends hand.

The old river Tnima, winding its way through the land, had formed a rather large island behind the house. Long ago, the island had been planted with fruit trees. Now the mature trees were generous with their offerings, better than any store-bought candy or even any dessert made in our kitchen. Sweet and sour tamarindos , which made a refreshing drink when soaked in water; fragrant guayabas , brilliantly green outside with a sweet red inside; caimitos , round as baseballs, with a shining purple skin and a delicate, milky-white flesh; bittersweet maraones , vivid bells of deep yellow or red, each one with a delicious nut hanging below: the cashews that my uncle Medardito and my young aunt Lolita loved to roast over a campfire by the river.

And then there were the dozens of coconut trees, with fronds that swayed in the breeze and fruits that we treasured above all others. The water of the young cocos is sweet and fresh. As the coconut matures, the water inside slowly turns dense and smooth like a light gelatin. Later it becomes fleshier, but still soft and sweet. We loved to eat these treats right out of their shells. As coconuts age, their meat becomes hard and dry; it can then be shredded to make desserts. But the most highly valued kind of coconut treat took much longer to form. If a large, healthy coconut was kept at the right temperature in a moist and dark place, then perhaps it would sprout. If it did, and if someone knew how to open it at the right time, she would find that the thick, dry meat inside had pulled away from the shell and had gathered in the very center of the coconut as a soft, porous ball, the deliciously sweet manzana del coco or coconut apple.