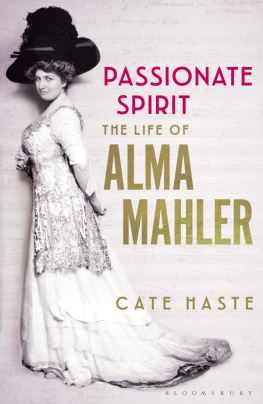

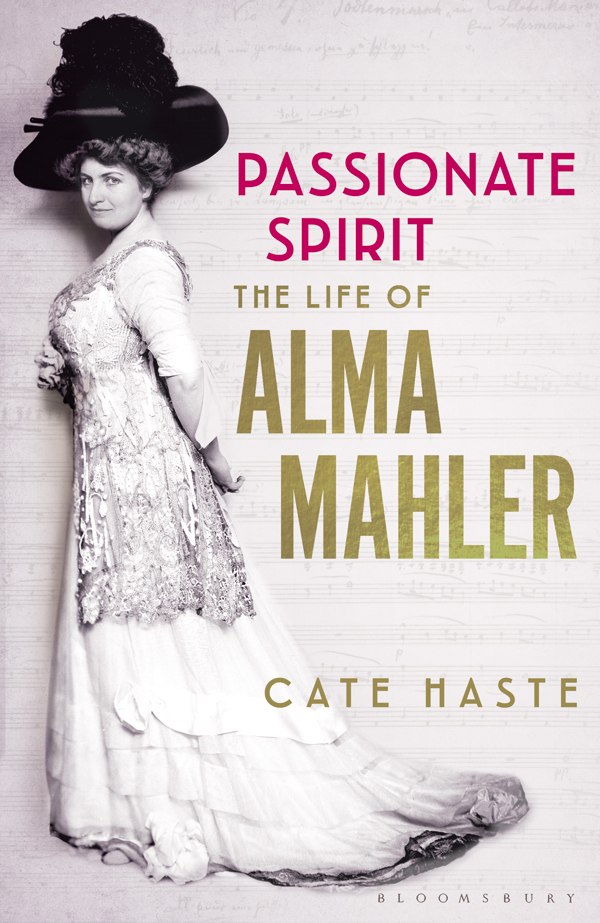

PASSIONATE SPIRIT

BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2019

Copyright Cate Haste, 2019

Cate Haste has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: HB: 978-1-4088-7832-3; eBook: 978-1-4088-7834-7

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

ALSO BY CATE HASTE

Keep the Home Fires Burning

Rules of Desire: Sex in Britain, World War I to the Present

Nazi Women: Hitlers Seduction of a Nation

The Goldfish Bowl: Married to the Prime Minister 195597

(with Cherie Blair)

Clarissa Eden: A Memoir From Churchill to Eden (ed.)

Sheila Fell: A Passion for Paint

Craigie Aitchison: A Life in Colour

To my grandsons Arthur and Eric

Contents

Alma Mahler was a woman of extraordinary complexity. Challenging, difficult, charismatic, generous, passionate and self-serving, she was the object of veneration and of mocking disdain, and the doyen of elite Viennese society for several decades. She inspired ballads, notably the satirist Tom Lehrers 1964 classic Alma, which spread her fame to a new generation, as well as several plays and films. Yet none has truly captured this exceptional woman.

In Passionate Spirit , I address her enduring and controversial legend and ask why, over half a century since her death, she still commands the fascination of scholars and readers alike. Alma was a powerful woman, a femme fatale who successfully defined her life through love. Many men fell in love with her, she drew widespread adoration, and great men needed her as their muse, the generous spirit who intuitively understood the springs of creativity that inspired their work. Alongside this attractive image runs the hostile legend of the seductress who used love to gain power over men, the threatening, devouring maenad, cold and calculating, who first beguiled men then ruthlessly rejected them. She becomes the self-serving egoist, who invented her own legend as the muse to genius by grossly exaggerating her importance in their creative lives. Her widely recognised musical and compositional talents are belittled, and any compositions of value are attributed to the influence if not the pen of either her teacher, Alexander von Zemlinsky, or her husband, Gustav Mahler. She is consistently and damningly accused of anti-Semitism, yet she had two Jewish husbands, one of whom she followed into permanent exile to escape the Nazis, several Jewish lovers, and a social circle composed mostly of Jews.

Clearly there are elements of truth in all these views. My aim is to weigh up the merits of these judgements against the available evidence, to portray the woman I discovered as I read her words and listened to her voice. And in so doing, I aim to reassess her legend and her legacy, to view her free from the screen of scepticism and the harshly judgemental tone of previous commentators on her life.

I like Alma Mahler. I particularly like the modern young woman who emerges from the pages of her early diaries written between the age of eighteen and twenty-two, when she was untrammelled by convention, and bent on realising herself and her talents despite the odds against her as a woman. And I find equally challenging and interesting the later woman who was surrounded in her legendary salon by Viennas glittering cultural elite, but was tormented by longing, afflicted by terrible tragedy, and still breached the boundaries of decorum in pursuit of a passionate life lived to the full.

The evidence in Almas case is controversial. She is routinely accused of massaging the facts to serve her own legacy: of suppressing or editing her husband Gustav Mahlers published letters to remove critical references to her, for instance acts seen, particularly by Mahler scholars (for whom she was for some time their principal source), as tampering with the archive. In addition she burned all of her own letters to him, which rouses suspicion about her intent and was frustrating indeed for scholars. These claims have been exaggerated into the prevalent view that anything written by Alma is bound to be inaccurate or self-serving, which in my view considerably undervalues her witness to her own life and the history she lived through.

With this caveat in mind, I have drawn as far as possible on primary sources. I have mined in more detail than previous commentators the private diaries Alma wrote in her late adolescence, between 1898 and 1902, which were published in 1998. I have quoted extensively for the first time from the unpublished typescript of her later diaries covering July 1902 to 1905, 1911, and 1913 to 1944, which are preserved in the Mahler-Werfel Collection at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania. Believed to be an accurate copy of her original diaries, they include some clear alterations in her own bold handwriting that I have acknowledged in the text. This invaluable source is the spine to my narrative of Almas life, the voice to which I have listened to penetrate this kaleidoscopic personality.

The diaries are the record of her most intimate feelings, her ambitions, her palpitating self-doubt, her candid comments on people and events. Since I used mainly the entries written on the day or very soon after events, they have an immediacy that conveys honesty rather than the structuring of recollection. And because a private diary provides the space to vent feelings and to work through emotions, they are raw and sometimes shocking in their candour.

Her unpublished 614-page typescript memoir, Der schimmernde Weg (The Shimmering Path), also in the Mahler-Werfel Collection, is an interim autobiography based largely on her diaries. It covers the period 190244 and though less immediate it was begun in 1944 and abandoned in 1947 it remains an important record. I treat her autobiography And the Bridge is Love , ghostwritten when she was seventy-nine and published in 1958, as a far less reliable source. It reveals a harder, more cynical persona, which lends credence to her hostile legend, and has been the principal source for at least two previous biographies of Alma. Recognising its inaccuracies, I have quoted from it only when absolutely no other source was available.

Almas Gustav Mahler: Memories and Letters , published in 1946, and Gustav Mahler: Letters to his Wife , edited by Mahlers respected biographer, Henry-Louis de la Grange, and published in 1995, are valuable sources. Additionally, several Archive Collections, particularly the Mahler-Werfel Collection at the University of Pennsylvania, include Almas correspondence with the numerous personalities in her life.

Few first-hand witnesses remain, so I am extremely grateful to Marina Mahler, Almas granddaughter, for several long and entirely enjoyable interviews, for her insights, her hospitality, and for the invaluable help she has given me throughout.

Next page