To Eleanor A. Pearson (1924 2019), in honor of the stories you told me about your beloved girlfriends at Sunnyside Park.

To Twyla, Pera, and Chloe, as you embark on your own journeys, may you experience the joys of special friendships.

And of course to Phyllis Bosco who encouraged us all to follow our bliss, thank you for the inspiration.

Chapter 1

Seren d ipity

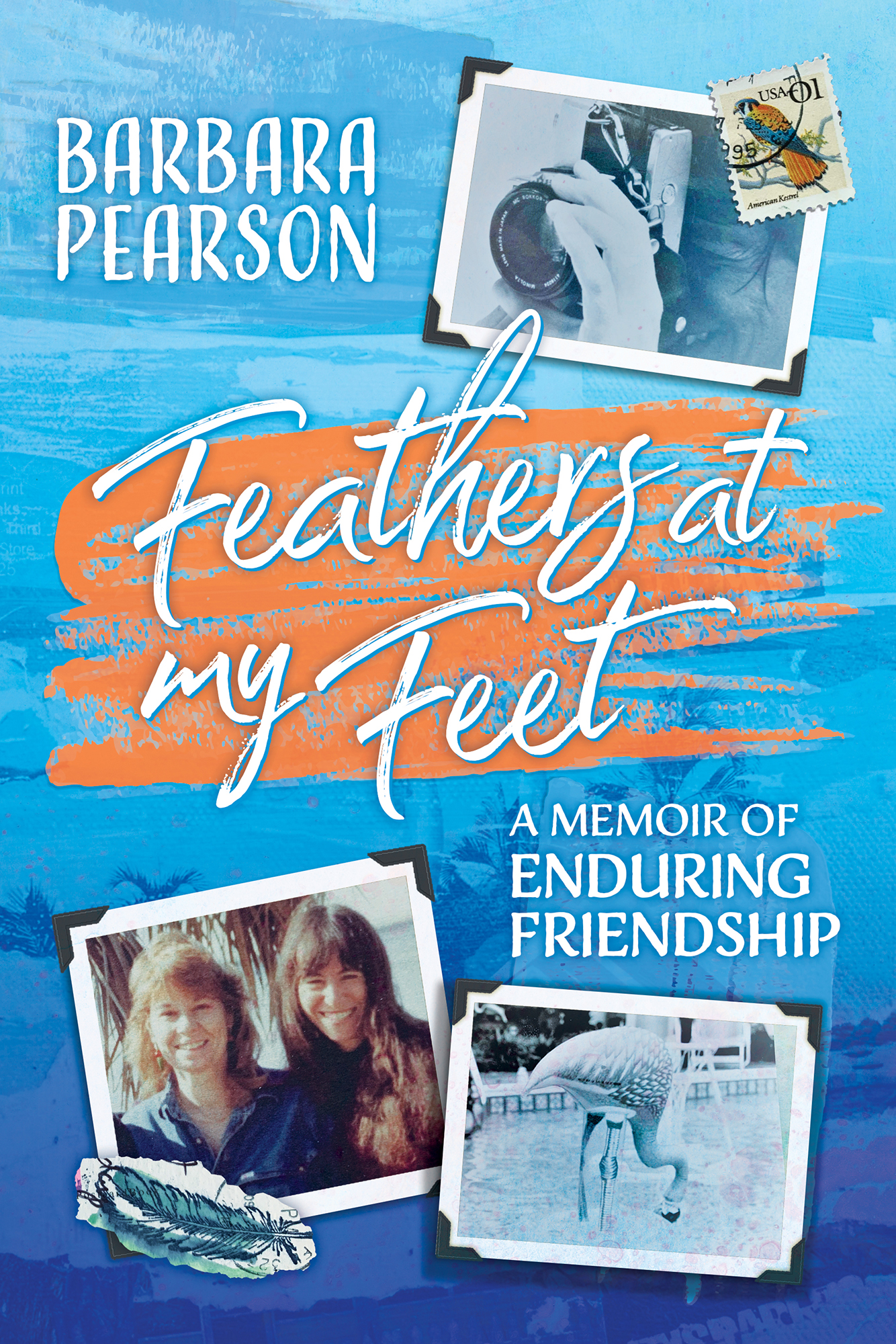

I knew of Phyllis Bosco long before we actually met in 1980. An artist, teacher, and activist, she was a longstanding celebrity in my current hometown of Tallahassee, Florida. Her presence could be found everywhere from museums and galleries to the posters inside city buses. At every art show, her mixed-media pieces boogie-woogied while paintings displayed next to hers simply waltzed. A true Florida artist by upbringing and context, her art danced to magical mixtures of surf, sky, and sandbars. Splashes of turquoise. Splotches of flamingo pink. Sashes of aqua sewn directly into the canvas.

Phylliss legendary past provided fodder for side comments from strangers who knew only her work and delicious long-winded accounts from people who knew her well. She had traveled to Mexico on Spring Break with three friends crammed into a VW bug. Shed protested against the Vietnam war with the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) on the Florida State University campus and revolted against the no pants rule for women at the universitys library. Shed left a salaried position to travel through Europe without income or a promise of a job when she returned. These are some of the stories etched in my mind; of course, there are many more.

At the time we met, I was a novice art teacher pushing an art cart (a classroom of supplies on wheels) along the covered walkways of one-story elementary schools. The classrooms lined up in rows like shoe boxes. To broaden my students worldview, I showed them slides of African masks, Impressionist paintings, and Picassos collages. I brought in fliers from art shows I had attended featuring work by local artists such as Phyllis Bosco. Back then, I couldnt imagine owning original art, much less one of her pieces.

One day a friend called. I have a Phyllis Bosco, she said.

Jealousy hovered over my congratulatory words and questions. Where did you get it? How much? Shortly thereafter, I set aside money meant for groceries and purchased my own Phyllis Bosco at the LeMoyne Art Foundation. A wood-framed, five-by-seven abstract pastel that reminded me of a beach illuminated by a large sun or moon. I have it to this day.

At last, when serendipity brought Phyllis and me together, it was not in Tallahassee, a small college town where bumping into each other would have been natural, but on one of my trips to New York City to visit my mother. That summer, Democrats were affirming Jimmy Carter as their presidential nominee at Madison Square Garden. Phylliss then husband, a journalist for the Associated Press, was covering the proceedings, and Phyllis could never resist a tagalong trip to the Big Apple.

She and I were both at the Whitney Museum flipping through postcards and prints in the gift shop. Adjacent to where we were standing was Calders Circus, a world of wire limbed clowns and yarn-maned lions. Engrossed in our own discoveries, oblivious to those around us, she and I collided.

Hi, Phyllis said with a smile that stretched across her angular face. Her eyes sparkled. Arent you from Tallahassee?

I gasped, grinning with delight that I had bumped into my favorite artist and astonished that she recognized me.

She leaned in from her shoulders, edging her face toward mine. Olive-toned skin, a strong nose, long limbed, the movement of an exotic bird. A small braid sectioned of long dark hair fell across her face.

As a redhead you stand out in a crowd, she said, laughing into her words.

Thats when I noticed her voice: high pitched but soft, full of breath, giggly but not silly, a whisper and a hum as if she were impartingjust to youthe most provocative secret.

You look so familiar, she continued. Have we met, maybe at an art show?

I am from Tallahassee, an art teacher, but I dont believe weve met. Youre Phyllis, arent you, the artist? I have one of your pieces, a small one. I love your work, and I...

Phyllis smiled, but then moved on to other topics. She commented on the Democratic Convention and her husbands assignment, our countrys general state of affairs, and the exhibits at the museum.

I nodded, adding a word here and there, but only half listening because I was so fascinated with her appearance. A flower child, for sure, with dangling peace-symbol earrings and fringed camel-colored boots. Layered vests: a tight one like a mans, and a tasseled loose one on top. When the strap of her hobo tote slipped from her shoulder, she scooted it back up with a twirl. Her hair, beads, and all that fringe rustled as if a summer breeze had miraculously whistled through the museums lobby.

Lets get together, she concluded, when we get back.

Yes, sure. Sure, yes, Id like that. I beamed, feeling a bit giddy and sensing that somehow, I had crossed a threshold from my ordinary life into something spectacular.

Chapter 2

T h e Art Teac h er

The path that led me to Tallahassee and Phylliss friendship involved rebellion, rootlessness, and discontent.

It started in New York during my last year of high school when Grandma proclaimed teaching as the perfect profession for me, and really, for all women. I held firm against that traditional female role. I was not going to be a teacher, or secretary, or nurse, period.

So, in the mid-1960s when I went to college to study art, I wandered from one program to another, left school only to return and quit again, wandered some more from one apartment and roommate to another, vacationed in Florida, met a man in a bar, and married him five months later.

Then the two of us wandered from one Boston apartment to another. A year later, our son was born; still we wandered. We packed our belongings into an old station wagon, drove south, and ended up on property east of Bithlo, Florida, where my husband tended beehives for the local Mormon Ranch. The job came with a house, rent free.

Soon we moved on, this time eighty miles southwest to Lakeland, an up-and-coming city with a minor league baseball team and a job opening with the Game and Fish Commission. Our second child was born at Lakeland General.

We lived in a cinderblock house with a carport on a corner lot with more dirt than grass. A white hunting dogone I dont believe I ever pettedhunkered in a kennel at the back of the property. During the day, with the baby on my hip, I cut peanut butter sandwiches into triangles for our lunch. I could hear my older son giggling through the open window as he sailed plastic boats in our inflatable kiddie pool. Before sunset, my husband would roar his company-issued pickup truck onto the yard so the driveway was left open for play. At night while everyone slept, I wrote in my journal.

This lifestyle was fine for my Florida-raised husband, but much too country for this New Yorker. I valued art museums over fish hatcheries and preferred shops along boulevards to john boats on lakes. I longed for a community of like-minded, artistic, and forward-thinking friends. I also thought my husband should have a college degree.

I flipped through catalogues and poured over maps, and after much consideration, selected Florida State University in Tallahassee as the ideal place for him. He was accepted, and we moved into family student housing, but to my chagrin, my spouse rarely attended class. Instead, he jammed with local musicians.