Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

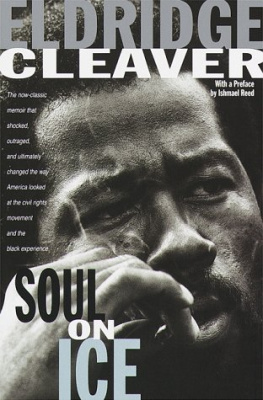

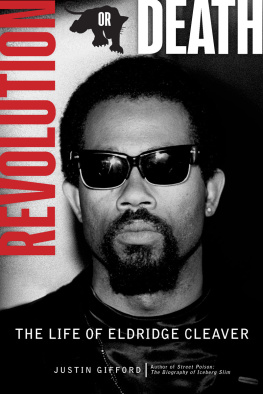

I first encountered Eldridge Cleaver during my senior year of high school through the pages of Soul on Ice. For my generation, Soul on Ice was one of the three classic works of the Black Power era, along with The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Claude Browns Manchild in the Promised Land. Soul on Ice, however, was especially titillatingI know no more appropriate word to useboth because of Cleavers bold advocacy of the uses of Fanonian armed resistance in the next phase of the civil rights struggle, and in particular his somewhat obsessive fascination with black male and white female sexual encounters. (I have to confess that I never understood, or accepted, his justifications of rape as an act of revolution, but even then I believed that we took this to be some sort of metaphor for radical self-assertion, but a metaphor run wild.) We read Soul on Ice against the backdrop of Black Panther politics, leather jackets, berets, and all the other trappings of a late sixties mythos of black revolution.

I could not possibly imagine, then, in 1968, that I would ever meet Eldridge Cleaver, a man whom some claimed to be the legitimate heir to Malcolm X. But I did: I met him in Paris, in December 1973. I had learned through poet Ted Joans that the rumors circulating around Europe were true: Eldridge and Kathleen were indeed living underground in Parisunderground in the imaginative French euphemism for political exile: illegal, unsanctioned entry, but with the full knowledge and complicity of the French government. In return for a small loan, Ted gave me Cleavers phone number; those were my terms. I hoped to launch my career as a journalist, which I had begun at the London bureau of Time Magazine in the summer of that year, with an exclusive interview with Eldridge Cleaver, revolutionary warrior, underground on the Left Bank.

We met at Shakespeare and Company, the historic English-language bookstore, nestled in the shadow of Notre Dame. He was three hours late; I was petrified. I wandered through the stacks, worrying that he would blow off our rendezvous. Truth be told, I wasnt certain that I wanted him to materialize. Alternating between fear that he would show, and fear that he wouldnt, I found myself thinking about a young James Joyce. I wondered if he ever was forced to wait here for the lofty T. S. Eliot for hours on end, just as I was waiting for Big Eldridge. My apprehension intensified the longer I waited in those dusty stacks of unsold, out-of-print American and English paperbacks. Huckleberry Finn just doesnt look the same staring up at you from a dust jacket near the banks of the Seine. I realized that I, too, longed to be a writer.

I nearly fainted when Eldridge Cleaver placed his huge right hand firmly but invitingly on my right shoulder. He had been watching me, apparently, for a long time, suspicious of my motives.

As we talked over the next two weeks in Eldridges studyhe sat in a barbers chair in the center of the room while I interviewed himit turned out that Over My Shoulder was the tentative name he had given to a novel he was writing. In time, as he relaxed, growing ever more reflective, I realized that Eldridge was far more of a writer, an essayist, than he was an activist, and that he was exceptionally intelligent and funny. I also realized that he was lonely in exile, despite his intellectual companionship with his wife, Kathleen, and that he was homesick and would rather be living in Babylon. It also became clear to me that his periods of asylum in Cuba and Algiers had convinced him that socialism, at least as practiced in Cuba, China, North Korea, and Russia, would not obliterate racism, a palpable presence on its own, even if inextricably intertwined with class relations.

Eldridge phoned me frequently when I returned to my graduate studies at the University of Cambridge. He even invited me on the now famous road trip during which he claimed to have had a road-to-Damascus conversion to Christianity. During that time, the great African American historian John W. Blassingame and I were negotiating to acquire his papers for the Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale. We both were stunned to learn that Eldridge had arrived at an agreement to return to the United States from exile. We were even more shocked when he announced his conversion, la Charles Colson, to a born-again variety of Christianity, including eventually a sojourn with the Mormons. I saw him occasionally at Yale, where he would come to visit Kathleen and their children Maceo and Joju while she completed her B.A. at Yale College and her J.D. at the Yale School of Law.

Even when I didnt understand Eldridges opinions, I still admired him immensely. Here was someone who, through the power of his own words, had written himself out of prison, replaced a criminal past with an intellectual future, started a family with a remarkably brilliant woman, Kathleen, only to give himself up to the American justice system soon thereafter. Eldridges peers from his Black Panther years resented his religious and political conversions, which caused an insurmountable ideological and personal rift between him and his friends. But he was always firm in his opinions and held on to his new beliefs despite the pain this rift inevitably caused him. Eldridge always had answers when I questioned him about his conversion to Christianity or his embrace of a most conservative approach to solving the problems of the black poor. He enjoyed debate, and debate we did!

Eldridge was an imposing man: he was very tall, handsome, and had a sharp wit that was delightfully challenging. His humor comes across in the writings Kathleen has ably collected here, just as his depth of knowledge, his passion and eloquence in expressing his beliefs come across in every line. This book is an enlightening testimony of a turbulent and controversial time, an essential historical record of the origins and development of Black Panther ideology, an exploration of the meaning of prison and exile, and ultimately the compelling saga of an unforgettable life.

These collected writings chart Eldridges lifetime in his own words and thus, for the first time, the full arc of the intellectual transformation of this exceptional mind comes to light. In Target Zero, Eldridge Cleaver writes himself firmly and squarely and into the history of American letters.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.,

W. E. B. Du Bois Professor of the Humanities,

Harvard University

The Eldridge Cleaver of national headlinesfugitive revolutionary, charismatic Black Panther, celebrated author of Soul on Ice had faded from sight by 1998. I heard less and less about his life during the eleven years since our divorce. On the afternoon of May 1, 1998, I was at a human rights conference at the law school of the City University of New York. I was listening to a friend explain why she disagreed with the panelist speaking about a Supreme Court decision on prisoners of war when an emissary from the dean interrupted us. To my surprise, she asked me to come to the office for a phone call. I guessed there might be some plumbing emergency at home, and when asked if I were sitting down, answered yes. The words Eldridge just died shocked me into silence. Then I went numb.