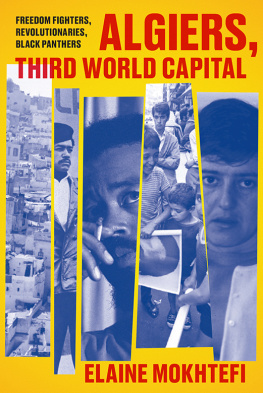

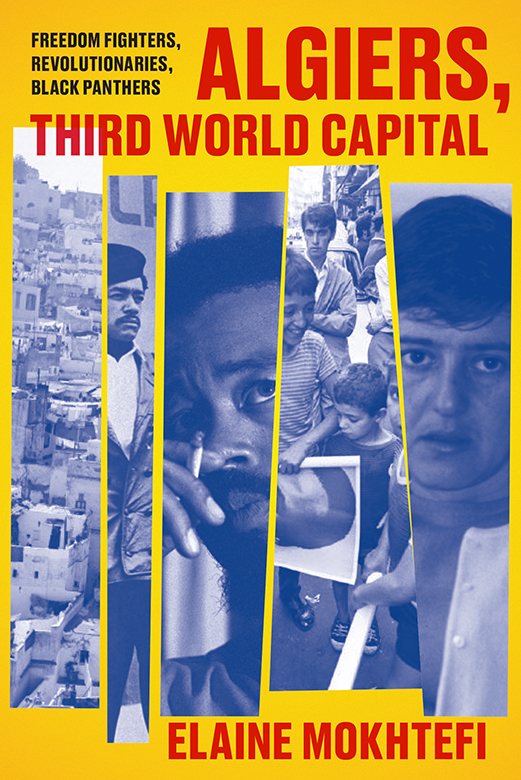

ALGIERS

THIRD

WORLD

CAPITAL

Freedom Fighters,

Revolutionaries, Black Panthers

ELAINE MOKHTEFI

First published by Verso 2018

Elaine Mokhtefi 2018

All rights reserved

Images reproduced with permission: Gamma-Rapho KO27312-A4;

Magnum, NYC37020; Magnum, PAR111338; Magnum, PAR409361;

Gamma-Rapho, KA10532TER_042; Magnum, PAR356568; Magnum,

PAR167091; Gamma-Rapho, RH080659; Magnum, PAR167078

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-000-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-001-3 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-002-0 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mokhtefi, Elaine, author.

Title: Algiers, Third World capital : Black Panthers, freedom fighters, revolutionaries / Elaine Mokhtefi.

Description: Brooklyn : Verso Books, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018003409| ISBN 9781788730006 (alk. paper) | ISBN 9781788730020 (united states)

Subjects: LCSH: Mokhtefi, Elaine. | Black Panther PartyPolitical activityAlgeriaAlgiers. | JournalistsAlgeriaAlgiersBiography. | Civil rights movementsAlgeriaAlgiersHistory20th century. | Algiers (Algeria)Politics and government20th century. | AlgeriaHistory19621990. | AlgeriaHistoryRevolution, 19541962.

Classification: LCC DT295.55.M65 A3 2018 | DDC 965.05092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018003409

Typeset in Fournier MT by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Nous avons vcu tous les ges tous les temps.

Mokhtar Mokhtefi

Contents

In December 1951, I boarded the Dutch ship Veendam in Newport News, Virginia; destination Europe. The seas were heavy and the small ship bobbed and tangoed across the Atlantic. It took two weeks to reach Rotterdam, its harbor dizzy with small boats darting in every direction. From there, I took a slow train to Paris. I was just twenty-three.

I had traveled in the States before. I had lived in small towns in New York State, Connecticut, Georgia, and Texas, and in New York City. But Paris was something else. Just six years after the Second World War, the city was still bandaged and suffering from the loss of status and self-respect. It had succumbed to Nazi occupation, but something of its magic was still intact. I discovered a grey city, a northern city, humid with daily rains; a sad place with sparks of genius, with an underlying sense of art, design, and fashion, and a strong belief in its place in history. I felt certain I would imbibe something basic from a world transitioning from the murky depths of war. I would drink at the fountain of the past and be better prepared for life, innocent American that I was.

In the Paris underbelly, however, dramas were being acted out that took some months for me to register and absorb. A subclass and subculture of Algerian immigrant labor was engaging in an existential battle for recognition and freedom. Little did I know when I rented my first room in a cheap hotel on the rue Saint-Andr-des-Arts, at the edge of one of the most crowded and intense of the North African quarters, how intimate and involved I would become with their struggle.

That the independence of Algeria would then lead me to participate in another fundamental battlethat of the Black Panther Party against the US power machinewas just as far from my imagination. There was no way I could have foreseen that Eldridge Cleaver would arrive clandestinely in Algiers, on my doorstep, and that the two of us would become collaborators.

I lived in independent Algeria for twelve years. In 1974, I was deported after a series of events stemming from my friendship with the wife of the former Algerian president. I have never been back. For years, friends have urged me to tell my story. I have finally taken the plunge. I bear no grudges. I feel no rancor. This is a story with a beginning and an end.

Paris was not a war-scarred city: it hadnt been bombed out. It was fixed in time, stationary and visibly weary, a city of past grandeur on display in urban castles, monuments, churches, royal estates and bridges, all under gray skies. There was no modern edge. The contrasts with the United States were striking, often chilling, and I was immediately taken. People were small or of medium height, somewhat drab and old-fashioned in look; if high fashion and couture were Parisian, they were not visible on the citys streets. There, women were appareled in straight or, at most, pleated skirts, stockings and sensible shoes. They projected an overall hue of gray or brown. Men wore hats or berets and ties, and everybody shook hands whether they knew you or not; friends and relatives kissed on both cheeks every time they met, which could be several times a day. The masculine working population mostly wore ill-shaped royal-blue cotton jackets and pants. No one spoke English, nor were we foreigners much appreciated for our attempts at their language: Thats not French, was the comment, meaning Youre killing our language and thats inadmissible. On the whole, people were not outgoing or especially friendly. There was a degree of mistrust, even defiance, behind their unsmiling demeanor. On the other hand, the food was great and for me unconventional, daring. I was soon indulging in shellfish, marrow, spices, herbs, game, innards, and an amazing array of desserts, aperitifs and wine. The whole of France closed down from twelve to two for the main meal, always wine-accompanied, either at home or in canteens or restaurants, then went back to work until seven. If you became a regular at a particular restaurant, you were assigned your own red-and-white napkin, kept in storage for you in a pigeonhole along the wall; the same might apply to unfinished bottles of wine. On descending onto the platform of a subway station, ladies in uniform, mostly war widows I learned, punched your ticket. City buses had open-air back platforms that agile travelers hopped onto by lifting a lightly attached chain. Cars were miniature and few; large American cars drew immediate attention, people gathering and commenting in detail on the trappings: the dashboards, logos, hubcaps, upholstery and the rest. Miles per liter was a never-ending subject of conversation.

There were exceptions to similarity and they were notable. My first night in Paris, I sat at a table in a restaurant near the toile with my friends Bill Friedlander and Naseem Beg. Imprinted on my memory in indelible ink is the image of a tall, fancifully-dressed woman who strolled by in a long, flowing winter coat and a broad-brimmed hat, all black. As I watched from the enclosed terrace of the restaurant, she lifted her gloved hand to drag on a cigarette through a holder; then, head held high, she released the smoke. She was laughing, detached from the man at her side. I had never seen anyone like her, the epitome of worldliness.

The second unforgettable image I encountered when out walking the following morning. On the Left Bank, in the doorway of a building near Notre Dame, I came across two older women enclosed in shawls and long dark skirts, round-shouldered, their graying hair swept up into loose buns. They were talking under their breath with barely a gesture, immobile. It was my first encounter with the French concierges, lodged in practically every Parisian building at the time, who carried out the duties of American building superintendents, but also acted as quasi-official informants for the police.