Portions of Third World Dreams, Fanon as Prophet, Algeria as Revolutionary Mecca, and The Camera as Gun were published in Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Black Freedom beyond America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012).

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.

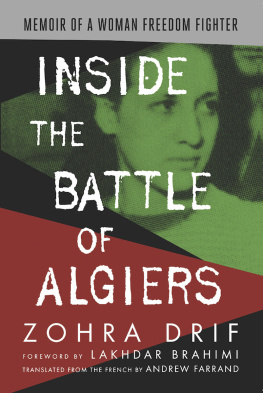

T HE B ATTLE OF A LGIERS IS STILL BEING WAGED, only now on a planetary scale. Everywhere the unrest is permanent, and everywhere the war declared on it is perpetual. Gaza. Ayotzinapa. Compton. Lagos. The world is a crime scene, with borders drawn in chalk outline. Security and order define and refine statecraft, resurrecting the unruly as the specter and threat to peace and stability. Police forces have proliferated. Brussels and Paris have been locked down. So too was Boston. Baghdad and Kabul are the laboratories; so too was Detroit. The threat perception is amorphous, boundless, everywhere, mirroring and mandated by the necropolitics of racial capital. The checkpoint is mobile and the barbed wire is ambient, while the guillotine looms. Counterinsurgency is the strategy and the tactic. The Law is an inconvenience and ethics a mere contrivance. House-to-house sweeps, gang injunctions, militarized borders, stop and frisks, surveillance aircraft, drone-fare, torture, indefinite detention, targeted assassinations: these are the predicates for liberal democracy and the protection of white life. The state of exception is the rule.

Though The Battle of Algiers (dir. Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966) was made fifty years ago, its as if it never ended. From the corridors of power to the tunnels of Gaza, we are seemingly still living the film. Only now its being billed as the War on Terror, a sequel to another prequel that is part horror, part absurdist drama, and part dystopic sci-fi, where mosques have become morgues and killing fields turned to theme parks. The names of the droned, tortured, and maimed cant even be mentioned. And if they are, theyre mispronounced. Amid the carnage, some wield the dialectic and others the gun, while the hunt for Ali La Pointe continues...

Prior to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the largest antiwar protest in history took place throughout the world. But to no avail. President Bush dismissed the protestors as a focus group, unleashing the bombing campaign that was known as Shock and Awe. Soon after the invasion, in late 2003, the Pentagon invited the military brass to a screening of The Battle of Algiers, and the teaser read,

How to win a battle against terrorism and lose the war of ideas. Children shoot soldiers at point-blank range. Women plant bombs in cafes. Soon the entire Arab population builds to a mad fervor. Sound familiar? The French have a plan. It succeeds tactically, but fails strategically. To understand why, come to a rare showing of this film.

Re-released by Criterion DVD Collections shortly after the Pentagon screening, including a theatrical run as well, The Battle of Algiers is widely considered the greatest political film of all time, having won numerous prestigious international awards, including being nominated for three Oscars. It is mentioned by filmmakers as diverse as Mira Nair, Paul Greengrass, Spike Lee, Steven Soderbergh, Oliver Stone, and Julian Schnabel, among others, as being deeply influential on their own work. But the resurgence of the film in the post-9/11 context has been both troubling and telling.

In addition to the Pentagon screening, the film was mentioned in a congressional hearing titled Preparing for the War on Terrorism just nine days after 9/11. In speaking about al-Qaeda,

Also, Richard Clarke, the doyen of the national security establishment, who worked for Presidents Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Clinton, and George W. Bush in various high-level capacities, including as chief advisor on the National Security Council from 1998 to 2003, would come to prominence as the critical voice in the political class after leaving the George W. Bush inner circle. In expressing his disagreement with the approach to counterterrorism under the BushCheney junta, Clarke argued that the attacks shown in The Battle of Algiers may have been the 1950s, but its all happening now in the 21st century.

In presenting a world violently defined by colonialism, only to then shatter that worlds seeming invincibility with a defiance that was at once shocking and gut wrenching, The Battle of Algiers gave voice and dignity to Algerian resistance to French colonial occupation. What interest would the Pentagon have in the film? How could a film that was so sympathetic to the Algeriansevocatively and poetically showing them organizing, targeting French occupation forces, and planting bombs in cafs and other public placescome to the service of the most powerful empire in the history of the world fifty years after it was released? And why did the Algerian War have such an impact on post-9/11 U.S. military policy, so much so that the Petraeus Doctrinethe blueprint for U.S. counterinsurgency in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewherewas deeply indebted to French military specialist David Galulas books Pacification in Algeria and Counterinsurgency Warfare?

The Battle of Algiers is an itinerant film, a nomadic text that has migrated throughout the world and has, echoing Edward Saids traveling theory, been embraced by a diverse group of revolutionaries, rebel groups, and leftists as well as revanchist, right-wing dictators, military juntas, and imperial war machines. The film has always been a battleground for competing ideas about power and politics at different historical junctures and in varying places around the globe. In fact, part of the films impact comes from the diverse sympathies it has engendered and the sheer range of interests that have identified with the film from across the political spectrum, whether it be in the favelas of Brazil or on the front lines of the Palestine Liberation Organization, the Tamil Tigers, the Irish Republican Army (IRA), or Black Power; from the war rooms of the Pentagon to the courtrooms of the Panther 21 trial; from the factory floors in Iran to the palaces where Dirty Wars were planned; and from community centers in Los Angeles to art house theaters in Havana, Mexico City, and Montevideo.