Also by LARRY TAYLOR

John McTiernan: The Rise and Fall of an Action Movie Icon (McFarland, 2018)

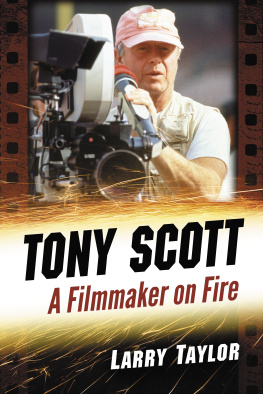

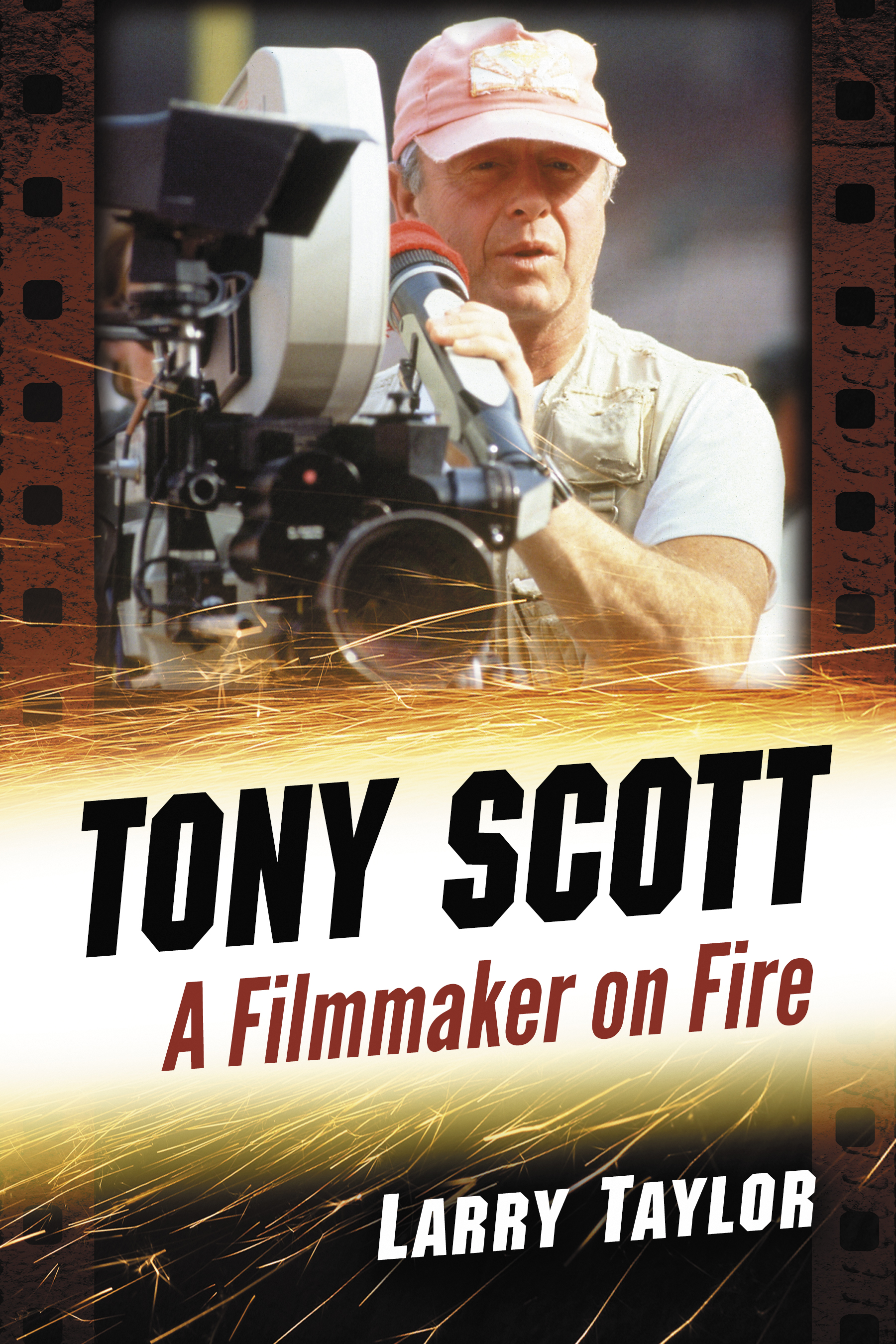

Tony Scott

A Filmmaker on Fire

LARRY TAYLOR

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3549-1

2019 Larry Taylor. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: Director Tony Scott on the set of the 1996 film The Fan (TriStar Pictures/Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Brandy, my Alabama.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to my mother, my father, my family and my friends. And a special thank you to Stephen Goldblatt, Bruce McGill, Dariusz Wolski, and Phoef Sutton for taking the time to contribute to this book on one of the more beloved filmmakers of a generation of action fans.

Preface

Tony Scott has always been a part of my cinematic life, and a part of the lives of an entire generation of action-movie fans. His movies were bold and bombastic, but they were never boring, no matter the warts. His life is fascinating, and his death confounding and tragic; it ripped a hole in Hollywood.

With extensive research, including news reports, biographies, interview archives, audio commentaries, documentaries, and one-on-one interviews with actors, writers, and crewmembers who worked alongside Tony Scott at different points in his career, I was able to paint a complete picture of a life lived to its fullest.

From the gray skies of northern England to the sunny shores of Southern California, I trace the tumultuous career of Tony Scott. Its about passion and love, about success and failure, about the importance of determination and focus in the face of adversity, and its about a dark end nobody could have predicted.

Introduction

The 1970s in Hollywood were a time of great discovery, a fertile ground of creativity that helped free the industry from stifling studio productions that had grown stale in recent years. As Dennis Hopper, Peter Fonda, and a young, unknown actor with a grin a mile wide named Jack Nicholson rode across the big screen in 1969s counterculture touchstone Easy Rider, they effectively stoked the fire of creativity that would lay waste to the Hollywood studio system for the better part of a decade.

William Friedkin, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Bob Fosse, Hal Ashby, Steven Spielberg, and a cavalcade of independent artists and filmmakers all helped change the landscape of cinema during the 70s. It was an exciting time of invention and innovation, unofficially kick started a second time with Friedkins documentary-style police thriller The French Connection dominating the Academy Awards; likewise over the next few years with Coppolas two Godfather films, both of which won Best Picture and changed the tone and depth of the gangster genre forever. Martin Scorsese brought cinema to the criminal underbelly of New York City, to the world he knew the city to be, with Mean Streets and Taxi Driver. Steven Spielbergs Jaws proved to be ground zero for the summer movie season and helped usher in George Lucas and a science-fiction adventure called Star Wars.

And then, it all came crashing down.

Michael Cimino, upon winning Best Director and Best Picture in 1978 for his searing, epic Vietnam melodrama The Deer Hunter, would take his newfound creative clout and subsequently send an entire studio to the brink of bankruptcy. Heavens Gate, Ciminos lugubrious western set against the backdrop of the Johnson County War in Wyoming, would give way to conflict and creative madness as Cimino drove the budget, and the cast and crew and producers, through the roof; when the dust settled, Cimino showed executives at United Artists a five-hour, twenty-five-minute melodrama, the very definition of creative excess run amok. While he was forced to cut it down, Ciminos eventual three-hour, thirty-nine-minute version was still a mess, and did very little in the way of quelling concerns. United Artists was in the hole, Cimino had been an unbearable collaborator, and other studios noticed the trouble and steadily backed away from giving filmmakers carte blanche with their projects.

Heavens Gate was not solely to blame for the decline in unbridled independent cinema. The worldmore specifically, the United Stateswas changing, slowly coming out of its hangover from two decades of conflict in Vietnam. Government distrust and general cynicism, which had played a major role in so many films of the 1970s, was disappearing into the background, overwhelmed by the hedonistic America First attitude of the countrys new commander in chief, a former actor named Ronald Reagan. No longer was paranoia and distrust the collective mood of the countrytimes were changing, getting brighter in America, and studios were back in charge of their budgets.

In 1981, Sir Richard Attenboroughs biopic Gandhi would win Best Picture; Amadeus, one of the greatest films of the 1980s, a bold, epic production from Milo Forman, won Best Picture in 1984. The next year, the Oscar went to Sidney Pollacks historical melodrama Out of Africa starring Robert Redford and Meryl Streep. Nineteen eighty-seven belonged to The Last Emperor, and Hollywood was humming along with prestigious pictures from the blue-blood studios.

On the other side of the coin, blockbuster films were getting bigger and bolder, and they began steering almost exclusively towards the franchise model, while genre filmmaking fractured into dozens of new avenues on the independent circuit. Spielbergs Indiana Jones films were a smash hit, as were Robert Zemeckis Back to the Future trilogy, and the two Star Wars sequels in the early 1980s remain the second and third highest-grossing pictures of the decade. New technology was making the impossible possibleat least on the screen.

It turned out to be the perfect fertile ground for someone as lavish and colorful and daring as Tony Scott.

It is difficult to picture Tony Scott sitting at an easel, because it is difficult to picture Tony Scott sitting at all. Born into a working-class British family, under the ashen skies of a heavily industrial Northern England, to a soldier and dock-worker father and a mother who ran the home with a loving iron fist, Tony Scott followed in his middle brothers footsteps and gravitated towards creative disciplines, never stopping for a moment to take a breath. He wanted to be an artist, a painter, to escape the doldrums of Northern England, and he tried for years to make it happen. But the overwhelming allure of a steady income and the promise of fast cars and Southern California chateaus soon convinced Scott to alter his course.

Over the next few decades, and with a little help from his friends, Tony Scott began his journey to becoming an icon. Scott was a man who always seemed to be moving forward at a breakneck pace, in work and in life; he lived with the throttle pressed to the floor, and his thirst-fueled motor helped him create some of the more eclectic and experimental action films of an era when the genre was coming into its own. He loved the life as much as the art he was making, and he lived his life to the absolute, ultimate potential every day.

Next page