Table of Contents

For Maseeh

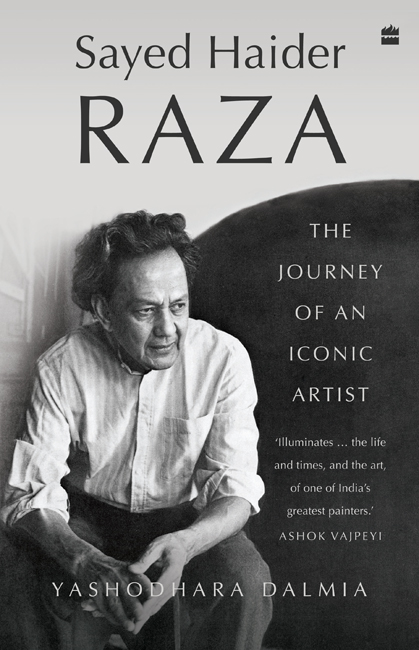

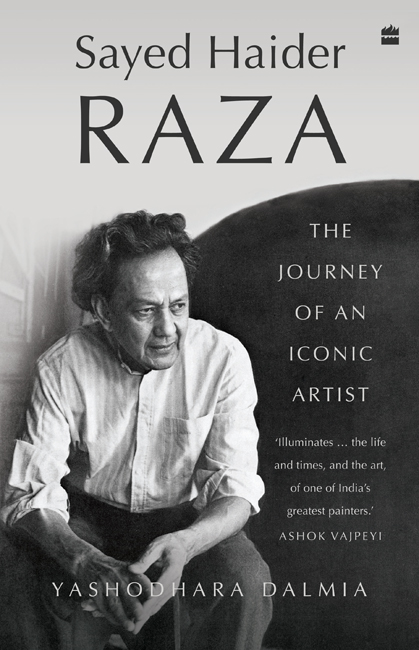

The hues and colours, struggles and anxieties, aesthetic vision and nobility of spirit of Sayed Haider Raza have been meticulously and rigorously explored by the outstanding art critic Yashodhara Dalmia in this first-ever biography of the great Indian artist. It illuminates, in an engaging and unprecedented manner, the life and times and the art of an iconic figure.

Ashok Vajpeyi, Poet and Cultural Critic

This is a compelling biography of a master artist who impressively represents the secular enthusiasms of modern India. Dalmia opens a window to reveal a landscape of changing art practices and transforming histories as she carefully traces the arc of Razas multi-hued life and work.

Abhay Sardesai, Editor ART India

Sayed Haider Raza traces the journey of a major twentieth-century painter, whose life and work straddled the art worlds of France and India. Dalmias fine-grained narrative digs deeply, illuminating how post-war decolonization enabled artists from elsewhere to pry open and enrich modernism, transforming it from a parochial Western school into a global movement. A rewardingly rich account for enlarging perspectives on trajectories of art practices in the twentieth century.

Susan S. Bean, Curator and Scholar

Contents

I t was when Raza passed away that I thought of and was commissioned to write this book. Not only was it a feeling of a grave absence but in many ways it was the loss of an epic generation of artists which was engrossed with art and art-making rather than its paraphernalia. Their masterly techniques gave us some of the richest practices in art history. The grace and humility with which they met people from all walks of life made them irreplaceable. Sayed Haider Raza seemed one of the last of that generation and his irrevocable loss was to make a big dent in the art world.

To write about Raza was to encounter two different worlds India of the 1940s, now lost forever, and Paris, France of the next few decades with its post-war rubble and rise, and the last remnants of its modernist practices which continued to inspire artists from South Asia and elsewhere. It was their collision and coexistence which marked the heady period that formed the matrix of Razas practice. The constant oscillation between these realities created the splendid intermixing of metaphor and mtier in his work. It would also be the intertwining of their separate existences that made Raza the polyglot personality that he was and richly infused his art. It mixed seamlessly in his personal life, often juxtaposed dexterously with his daily chores. He would, for instance, begin his day with a remembrance of Islamic, Hindu and Christian teachings or start painting after reading a verse by a poet like Rainer Maria Rilke. His soires at home would have a mix of French and Indian friends and the music would come from Ravi Shankars sitar. He was one of the few artists whose work and life were inscribed by actually living in a cosmopolitan Western city like Paris. But when asked if he felt exiled from India, he would say that he had never left home. Perhaps the truth was that he was a global citizen of his time rooted in the country of his birth and yet living in Paris.

In tracking his long life, we encounter countless people and events which are embedded like nuggets in a piece of ornament. It was his absence which created the need for this book and yet also added to the difficulties. Most of his acquaintances have passed away and could, therefore, leave behind no account of their engagement with his life. Added to this is the fact that many letters and notes exchanged by him are now in Pakistan, since his entire family had been compelled to leave after Partition. There were, however, a few artists who vividly remembered their times with him, the most notable amongst them being Krishen Khanna. The children of a few friends of his have preserved some of his letters for he was a prolific communicator. Most importantly, it was Raza himself who had retained a vast archive of correspondence, notes, photographs and virtually every slip of paper from his adult life, which came to the rescue of this book.

As a biographer I do not presume to have covered every event in Razas life, for there were numerous and now rest with the artist, but the significant ones have been documented. It is interesting to note that in his early years, his correspondence with F.N. Souza was the most prolific and that there were nascent plans to make the Progressive Artists Group into an international forum for modernism. Even if this ambitious scheme did not go very far, it is commendable for its vision and foresight. Razas friends and other artists from India visited him often in Paris and learnt from him and his surroundings; and in turn kept him abreast of the prevailing situation in India and shared with him his great yearning for his homeland. The most frequent of these visitors were Krishen Khanna and Ram Kumar their letters to him provide a vivid account of his life in Paris and the difficulties he surmounted to make a life for himself there.

When Raza married Janine Mongillat, a fellow student at the cole nationale suprieure des Beaux-Arts, it was to be a long, rewarding and stimulating relationship which transformed their lives. Their continuous dialogues and exchanges, while retaining their separate artistic profiles, were to provide the role model of a truly generative and rich partnership. The lesser-known fact was his passionate desire for her that he seldom revealed, perhaps because of a reticence in these matters since his childhood, but which emerge in his letters to her. This book highlights a seminal period of their courtship where his letters provide a glimpse not only into the intensity and passion which he felt for her, but also his erudition as he ruminates on writers and poets from Gide and Rimbaud to Rilke and Rumi. Though younger in years, Janines death precedes him and leaves him enormously bereft. His attempts to overcome his subsequent loneliness, which he mostly succeeds at by immersing himself in his work, are also recounted in this volume.

Razas relationship with other French artists, his correspondence with the Berkeley professor Karl Kasten who invited him for a stint there and which transformed Razas work, his consistent dialogue with prevailing trends in art, are some of the other factors which emerge. He did at all times retain an equidistance from both pure formalism as well as an effete revivalism in his work. As he stated, My present work is the result of two parallel enquiries. Firstly, it is aimed at pure plastic order, form-order. Secondly, it concerns the theme of nature. Both have converged into a single point and become inseparable. The point, the bindu, symbolizes the seed-bearing potential of all life, in a sense. Its also a visible form containing all the essential requisites of line, tone, colour, gesture, and space.

It is with some astonishment that we discover his passionate involvement with Hindi writers, Indian culture and music while living many miles away in a completely different sphere. He visited India every year and travelled to different places in it to stay in touch with and to overcome his longing for the country. But the most touching of those trips was when he visited his birthplace and the teachers of his formative years to whom he felt overwhelmingly grateful. It was characteristic of Raza to not only remember each one of them, but also to believe that it was their contribution to his life that had made him reach the heights he had. His consistent involvement with Hindi poetry made him inscribe those in his paintings. When he did return to India at the end of his life, it was to Delhi the city which his grandfather had fled from originally during the Uprising of 1857, making the wheel come full circle.

![Keith Bain - Frommers India [2010]](/uploads/posts/book/43617/thumbs/keith-bain-frommer-s-india-2010.jpg)