Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2010 by

CASEMATE

908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083

and

17 Cheap Street, Newbury, Berkshire, RG14 5DD

Copyright 2008 Lee Allen Zatarain

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-935149-36-1

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-0336

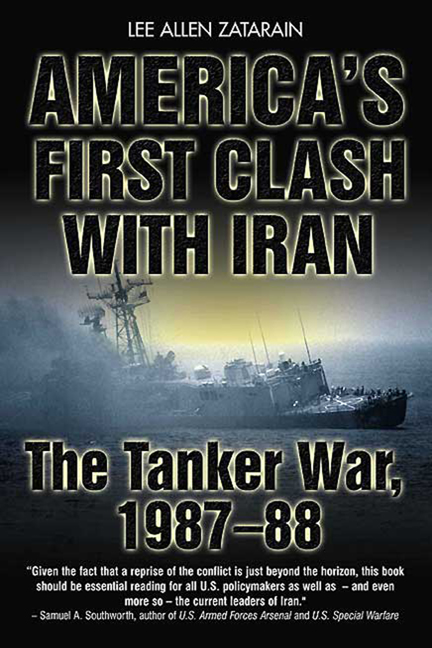

Originally published in hardcover in 2008 as Tanker War: Americas First Conflict with Iran, 198788.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

For a complete list of Casemate titles please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146

E-mail: casemate@casematepublishing.com

CASEMATE UK

Telephone (01635) 231091, Fax (01635) 41619

E-mail: casemate-uk@casematepublishing.co.uk

INTRODUCTION

In 1987 and 1988, the United States fought an undeclared naval war with the Islamic Republic of Iran in the Persian Gulf. That war is little remembered, even though it involved the largest surface battle fought by the U.S. Navy since the Second World War, a mark which still stands. Perhaps it is mostly recalled today in connection with the Navy warship USS Vincennes accidental shoot-down of an Iranian commercial airliner, killing nearly 300 innocent civilians.

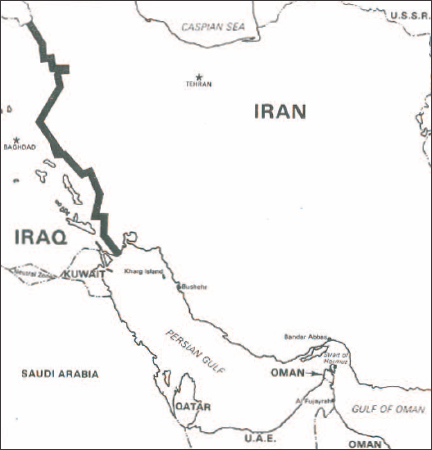

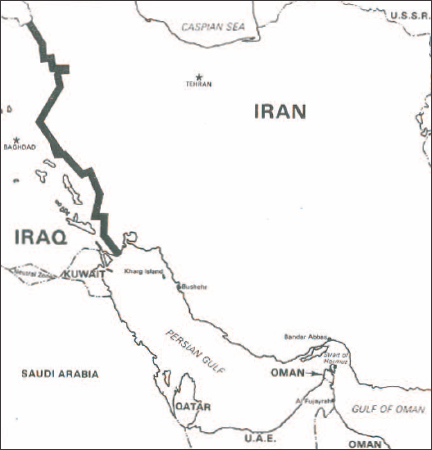

For a variety of policy reasons, the U.S. decided to intervene in the Gulf in 1987 to protect Kuwaiti-owned tankers from Iranian attack. Shipping in the Gulf had come under increasing attack from both Iran and Iraq in what became known as the tanker war. That war was an off shoot of the brutal Iran-Iraq war begun in September 1980. The IranIraq war was predominately a grinding land struggle. It was nominally fought over the ownership of the disputed Shatt al-Arab waterway, which ran from the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers for some nine miles down to the Gulf. The waterway formed the southern border between Iran and Iraq, and was the latters only outlet to the Gulf. Iraq claimed full ownership of the waterway, Iran claimed ownership to its centerline. Iraq had been forced to accept the Iranian claim via an agreement known as the 1975 Algiers Accords.

Irans monarch, the Shah, had been overthrown by an Islamic-dominated revolt in 1979, resulting in the radical Islamic prelate, the Ayatollah Ruollah Khomeini, seizing the reins of power. Iraqs secular dictator, Saddam Hussein, was directly threatened by the bubbling cauldron of the Iranian revolution on his doorstep. Khomeini described Saddam as a puppet of Satan. In 1980, he called on Iraqis to over throw Saddam and cleanse the country of his atheistic rule. An increase in armed clashes along the border mirrored the escalating rhetoric. On September 17, 1980, Saddam appeared on Iraqi television, tore up the 1975 Algiers agreement, and claimed sovereignty over the entire Shatt al-Arab. Faced by the threat of a militant Islamic revival in his own country and presented with the opportunity of the Iranian military built up by the Shah having been greatly weakened by the Iranian revolution, Saddam decided on war.

On September 22, 1980, nine Iraqi Army divisions attacked across the Iranian border. Iraqi forces seized a sizeable foothold in the valuable oil producing southern Iranian province of Khuzestan. Iraqs war aims were relatively limited. Saddam thought he could take advantage of a tilt in the regional balance of power from Iran to Iraq to resolve the territorial disputes in Iraqs favor. He could also put an end to the threat to his rule by putting Khomeini in his place, perhaps even precipitating a collapse of the clerical regime. Unfortunately, he had made a near fatal error. He was indeed attacking a weakened regional rival, but he was also attacking a revolution.

Following the overthrow of the Shah, a tide of fundamentalist Islamic terror had swept over Iran. Those suspected of anti-revolutionary activities were arrested by groups of students and workers organized around a mosque or a mullah. Zealots threw acid in the faces of women who failed to wear veils, or slashed them with razors. Revolutionary tribunals did a brisk business in trials and executions. Khomeinis grim vision of a true Islamic society was imposed on Iran. He declared music to be corrupting. Swimming pools and sports clubs were closed. Revolutionary Guards raided homes, looking for objects of corruption such as playing cards and chess sets.

In November 1979, some 80 students seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran. While not ordered by Khomeini, he found that the students act played so well that he got behind his followers and gave the seizure his blessing. The resulting prolonged hostage crisis led to the humiliating failure of a U.S. rescue attempt. Public frustration in the face of U.S. inability to resolve the crisis took a heavy political toll on the Carter administration. That frustration helped propel Ronald Reagan to the White House.

Absorbed in internal power struggles and in the midst of defying the U.S. with the embassy hostage seizure, Khomeinis regime did not feel much threatened by the limited Iraqi attack. Believing himself in a posi tion of strength with the initial success of Iraqs invasion, Saddam Hussein announced his willingness to negotiate a settlement. Iran refused. The Iraqi army continued its plodding advance against stiffening Iranian resistance. The Iranian defense really took hold at the city of Khorramshahr. The Iraqis were finally able to take the city, but losses were horrendous on both sides. By early 1981, the Iraqi advance had stalled. Given breathing space, Iran regrouped and counterattacked.

Starting in the fall of 1981, the Iranians completely wrestled the initiative away from Iraq with a series of advances. By May 1982, Khorramshahr was retaken. Saddam tried to declare a unilateral cease fire and withdrew his remaining forces from Iranian territory back to Iraq, where they assumed a defensive position. Iran was not so anxious to call it quits. Khomeini had a personal hatred for Saddam. He also saw the utility to his regime of an ongoing war with an external enemy. Calling it an imposed war, the regime sought to rally the populace against the invader, and behind it. The clerical regime could use the war to further consolidate its power and to provide a convenient rationale to suppress remaining domestic opponents by labeling them as traitors. Iran demanded impossible terms from Iraq as the price for peace, including the removal of Saddam Hussein and his trial as a war criminal. With its back to the wall, the Iraqi regime hunkered down.

If Iraq made a mistake attacking a revolution, Iran was now making one of its own: attacking a ruthless dictator who could and would deploy the resources of his state to the maximum extent possible to protect his position. Inflated by oil revenue, Iraqs financial resources were enormous. Its human resources were less impressive. Iraq had only onethird of Irans population, and its people also lacked enthusiasm for the war that Saddams gambit had plunged them into.

In 1982, Iran launched its first major assault into Iraqi territory, near the southern city of Basra. Others would follow. The attacks made headway and inflicted significant causalities on the Iraqis. However, the Iraqis were able to hold on by the skin of their teeth and prevent any major breakthroughs. What captured the attention of the world, and badly unnerved the Iraqis, was the nature of the Iranian attacks. Tsunami-like human waves, driven by the winds of surging Shiite religious fervor, repeatedly crashed against Iraqi lines. The attacks were made with what appeared to be a complete disregard for human life.