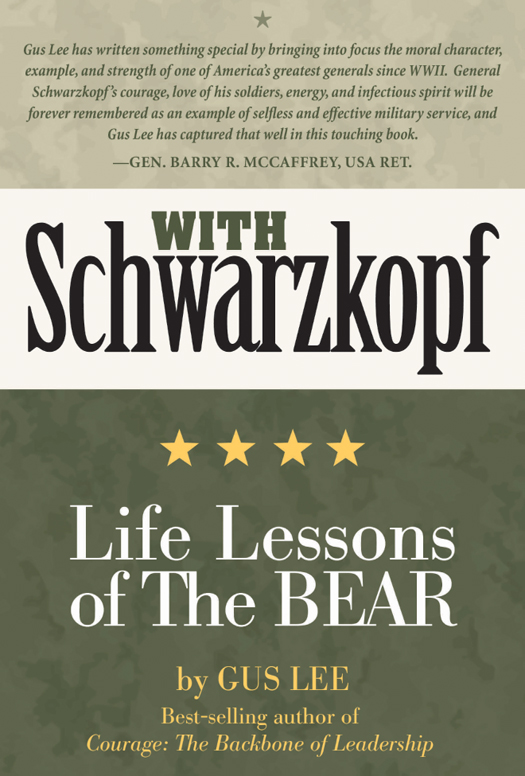

2015 by Gus Lee

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Production Editor: Christina Wiginton

Edited by Mark Gatlin

Cover design by Brian Barth

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lee, Gus.

With Schwarzkopf : life lessons of the Bear / by Gus Lee.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-58834-529-5

eBook ISBN: 978-1-58834-530-1

1. Schwarzkopf, H. Norman, 1934-2012Anecdotes. 2. United States Military AcademyBiography. 3. College teachersBiography. 4. Lee, Gus. 5. Military cadetsUnited StatesBiography. 6. LeadershipUnited States. 7. Character. 8. Conduct of life. 9. United States. Army. Office of the Judge Advocate GeneralBiography. 10. Chinese AmericansBiography. I. Title.

E840.5.S39L44 2015

303.34dc23

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the author. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these images individually, or maintain a file of addresses for sources.

v3.1

To my beautiful Diane, for everything. You said I could write and showed me the way.

To General H. Norman Schwarzkopf

For mentoring me and caring about our character.

TABLE OF

Contents

Preface

I n 1966 America, 63 percent of the public held high confidence in government, divorce was uncommon, and academic cheating was episodic. Riding an economic boom, many expected America to solve the problems of the world.

Today, research reveals that seven percent of the public has confidence in Congress, and 75 percent of Americans in high school, college, and graduate school routinely cheat. The Government Accounting Office reports that the frauds of the 2008 subprime meltdown, designed by educated elites, cost the nation 129 percent of GNP and millions of jobs. Generals, admirals, and more junior officers are routinely fired for ethical misconduct, while sexual harassment in the military and society remains a problem. Eighty-seven percent of U.S. managers said in a national survey by certified fraud examiners that they would fabricate data to make their organizations look better.

In 1966, a young major in the United States Army named H. Norman Schwarzkopf left the new war in Vietnam to reluctantly become a temporary engineering professor at West Point. To my very good fortune, I was one of his cadets.

He was committed to my self-improvement, making the next years among the most intense of my life. After a 20-year hiatus, I invited him to join a start-up company for which I worked and we reunited in a relationship that would span 47 years. Although we originally met in academics at West Point, and worked in business, his relationship with me was fundamentally moral, for it dealt with that which is unseen. He demanded facts but was driven to live in alignment with principles, and it was his very attractive habit to inspire others to do the same. Thomas Carlyle, a 19th century philosopher wrote, Every noble work is at first impossible. What the Bear did was noble; my struggles suggested the impossible.

Norman Schwarzkopf had once been a pudgy and self-acknowledged un-macho child with an alcoholic mother. Perhaps he believed in changing others because he himself had changed. In the aftermath of an historic triumph in the Gulf War, General H. Norman Schwarzkopf became one of the worlds most admired individuals, was offered the top position in the Army, was knighted by the Queen, and was guaranteed high elective office. He disliked Stormin Norman and enjoyed being known as the Bear.

He was officially a genius, intercollegiate athlete, missile engineer, and a superior soldier. But his unique gift was character. He tried to pound his will and intentionality about right action into his students with the fire of a medieval blacksmith. With occasional brain-rattling roars, he inspired me to strive, laugh, learn, and change in an attempt to forge a diffident person into a courageous individual.

It is now two days after Christmas 2014. Two years ago today, General Schwarzkopf died in his home in Tampa in the company of his family and his inner staff. I am writing in our oldest daughter and husbands home in East Nashville as their six-month-old son Jude chews a green wooden block and shows great interest in my feet.

H. Norman Schwarzkopf, I say to Jude. He looks up with a radiant smile. The Bear had a broad, infectious, almost boyish grin. When I was 20, Major Schwarzkopf filled my young mind with his ideals, cemented one principle and two rules of leadership into my heart, and altered the course of my life. I want our childrens generation, and Jude and his big cousin Mikey, to have access to the same life lessons that my mentor so freely passed to me.

When he retired from the Army, he refused vast powers, uncounted riches, and greater fame to be with his family, serve desperately ill children, energetically support little-known charities, and help lead organizations in protecting the nation and the environment.

He worried more about our commitment to be a right-minded and ethical people than he did about party politics or the might of potential enemies.

Every age yearns for a hero. At the dawn of the new millennium, most of America saw that hero in General H. Norman Schwarzkopf. Brilliant and knowledgeable, his enduring excellence was not within his cranium but within his chest; it was in his character and in his uniquely fierce commitment to develop high integrity in others.

Historians can easily count the few world figures who have inspired a nation to experience a hope borne of moral heroism. Americans of today have the opportunity to remember one of those few who, until recently, was still among us.

In 1966, I was, like many West Point cadets, frenetically overscheduled and given to musings about my coming greatness. I had become attached to my fears and self-doubts and fretted over short-term results.

Because I struggled with doing the hardest right, Id ironically become a target for reform by one of the great personalities of the age.

Its Always about Leadership

The general is the bulwark of the state; if he is strong at all points, the state will be strong. If he is defective, the state will be weak.

Sun Tzu

O n a Friday in mid-January 1991, a great war was coming in the Middle East. Early mobile phones were the size of Coke machines and cost as much as a small car, so routine communication came by the landline telephone. Ours rang with its alarm-like jangle. It was Colonel Bob More Beer Lorbeer, my tall, broad-shouldered West Point roommate, a wounded, decorated, and sober combat veteran whose nickname was phonetic and unrelated to his personal habits.