PICTURE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

U.S. Naval Institute: 1, 2, 16, 17, 20, 22, 36, 38, 48, 49, 61, 67, 69, 74, 77, 82, 85

U.S. Library of Congress: 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 21, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 34, 37, 39, 47, 50, 53, 55, 56, 57, 58, 63, 66, 70, 72, 73, 78, 83, 84, 91, 93, 96, 97, 100

Novacolor: 4, 13, 14, 23, 24, 25, 42, 45, 62, 75, 79, 80, 89, 90, 94, 99

U.S. Army Military History Institute: 18, 41, 46, 65, 95

Massachusetts Commandery Military Order of the Loyal Legion and the U.S. Army Military History Institute: 32, 33, 60, 87, 92

Indochina Archive: 40

South African Library: 59

Embassy of Finland: 64

Embassy of the Republic of Iraq: 81

Republic of Korea Mission to the United Nations: 86

U.S. Naval Historical Center: 98

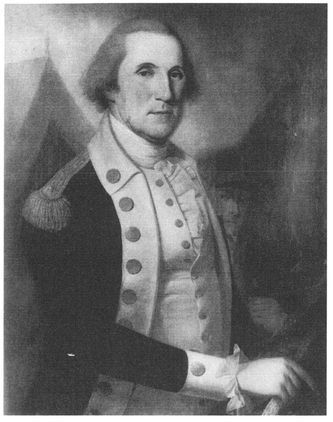

George Washington

American General

(17321799)

G eorge Washington, commander of the American Continental army and the first president of the United States, is the most influential military leader of all time. If identifying and ranking the top 100 focused on only great battle captains or brilliant military strategists, Washington might be far down the list, if included at all. This study, however, concerns influential military leaders, and within that parameter Washington ranks at the very top.

As the commander of the Continental army, Washington led an assembly of citizen soldiers he described as sometimes half starved; always in rags, without pay and experiencing, at times, every species of distress which human nature is capable of undergoing. With this ragtag army and his political ability to appease civilian commanders and gain support from other countries, Washington defeated one of the worlds foremost armies and brought independence to the United States of America.

Washington, born to a farm family on February 22, 1732, in Westmoreland County, Virginia, mostly educated himself by extensive reading of geography, military history, and agriculture. The young Washington also studied mathematics and surveying, which led him, at age sixteen, to join a survey expedition to western Virginia. In 1749, Washington became the official surveyor of Culpepper County.

Washingtons first direct military experience came with his appointment as a major in the Virginia colonial militia. In 1754, Washington led a small expedition into the Ohio River valley on behalf of the governor of Virginia to demand that the French withdraw from the British-claimed territory. He had his first taste of combat when the French attacked his company, forced its surrender, and sent it back to eastern Virginia.

Washington resigned his commission but then rejoined the militia in 1755 as a lieutenant colonel and aide to British general Edward Braddock. Back in the Ohio Valley once more, Washington was with the British column when the French and their Indian allies sprung an ambush, killing Braddock. Washington took charge of the withdrawal and led the survivors to safety. As a reward, Washington was promoted to colonel, and when the Seven Years War between Britain and France was formally declared in May 1756, he took command of the defenses of the western Virginia frontier.

Washington tried to join the British Regular Army, but when rejected, he returned to Mount Vernon at the end of the war. In 1758, Washington was elected to the House of Burgesses, where he served for the next seventeen years. During this time, he openly opposed the increasing British repression of the American colonies and the escalating taxation on life and commerce.

When the Continental Congress met in 1774, Washington represented his home colony of Virginia. Shortly after the American Revolutionary War began in 1775 with the battles at Lexington and Concord, Washington appeared before the Continental Congress in his militia uniform offering his service. By unanimous vote, Congress authorized the formation of a Continental army and appointed Washington its commander in chief, not so much for his military qualifications as for his diplomatic skills. With the American colonies experiencing distinct and hostile divisions between North and South, Washington appeared to be the only leader capable of uniting Americans in opposition to one of the worlds strongest armies.

Washington took command of the Continental army, formed from various colonial militia, at the siege of Boston in July 1775. He immediately organized his force, dealt with the loyalists, and attempted to form a navy. Familiar with the advantages of terrain from his experience as a surveyor, Washington occupied the unguarded Dorchester Heights, armed the high ground with cannons captured at Fort Ticonderoga, and shelled the British occupiers of Boston, forcing them to evacuate the city by ship in March 1776.

Wisely anticipating that the British would target New York City as a base from which to split the colonies along the Hudson River, Washington arrived in New York with adequate time to prepare defenses but evacuated when his soldiers, inferior in both numbers and training, failed in several battles with the British Regular Army in November.

By the time Washington retreated into Pennsylvania, his demoralized army totaled a mere three thousand soldiers. The British force of thirty-four thousand seemed to be waiting only for spring to finish off the American rebels. On Christmas night, 1776, Washington made his most daring, and famous, attack by crossing the ice-filled Delaware River and engaging the British Hessian mercenary garrison at Trenton. With few losses, the rebels captured nine hundred of the enemy and on January 2 defeated another small British unit at Princeton.

Neither encounter was a decisive victory, but together they did provide the first positive news for the rebels since Boston. Recruiting became easier, morale within the army rose, and more importantly, the series of losses had ended. However, Washington recognized that he could not defeat the superior British army in open combat. He also realized that he did not have to do so. Time was on his side. The longer the war lasted, the more likely it was that the British would tire of the expenditures and that some other, more threatening enemy would go to war against them.

Quite simply, Washington understood that as long as he had an army in the field, victorious or not, the newly declared United States of America existed. In 1777, Washington made only a perfunctory effort to defend the capital at Philadelphia and sent part of his army to upstate New York to stop a British invasion from Canada. Although he did not directly participate at Saratoga, the rebels won the battle because of his selection of excellent subordinate commanders and his willingness to give them the authority and the available assets to achieve victory.