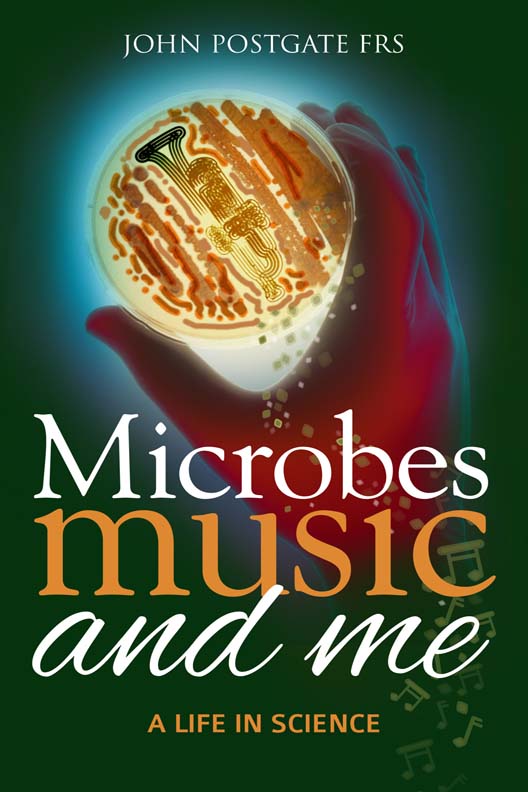

JOHN POSTGATE FRS

MICROBES, MUSIC AND ME

A life in science

All Rights Reserved.

Copyright 2015 by John Postgate FRS

Published by Mereo

Mereo is an imprint of Memoirs Publishing

25 Market Place, Cirencester, Gloucestershire GL7 2NX, England

Tel: 01285 640485, Email:

www.memoirspublishing.com or www.mereobooks.com

Read all about us at www.memoirspublishing.com .

See more about book writing on our blog www.bookwriting.co .

Follow us on twitter.com/memoirs books

Or twitter.com/MereoBooks

Join us on facebook.com/MemoirsPublishing

Or facebook.com/MereoBooks

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the copyright holder. The right of John Postgate FRS to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 sections 77 and 78.

The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them.

ISBN: 978-1-86151-102-7

Contents

Foreword

Accounts of present-day science written for non-scientists exist in abundance; I have written a couple on microbiology myself. In fact, such works have become a genre in their own right and even merit their own literary prizes. But only rarely do they can they deal with the human side of research. After all, painful as the thought may be to the average researcher, in the long run it does not matter who added this or that bit to our edifice of scientific knowledge: all that matters is that it be reliable, based on sound and reproducible observations.

Of course, in the short run the reputations and abilities of the scientists who report new scientific findings obviously matter enormously poor science will be neither believed nor funded but in the end science is impersonal. Both formal and popular scientific writings generally strive to retain that impersonal approach; only in scientific biography and history may personality impinge. Which is as it should be.

Can it be its very impersonality that makes science so arcane, frightening or boring, to non-scientists? For very good reasons, proper scientific writing rarely gives any hint of more human questions. How is science actually done? What possesses anyone to become a scientist in the first place? What does it feel like to do scientific research? What, in fact, do people actually do in laboratories or research stations? What sorts of people guide and lead scientific advance? How do the fragments of knowledge garnered piecemeal all over the world come together in the ever-growing edifice of scientific knowledge?

These can be very interesting questions, and the answers differ according to the branch of science and type of scientist being considered. But the answers also have a lot in common, too, and can bear strongly upon the impacts and directions of scientific advance, not to mention the reliability of its tenets.

So this is not a science book (though a lot of science will creep in), it is a book about doing science. It happened that I reached manhood in the mid-twentieth century, just as the transcendent importance of science to our social well-being had become accepted by most Western societies and their governments, largely because of the very obvious contribution their scientific superiority had made to the Allies victory in the then recent Second World War. Science had long ceased to be the province of amateurs; the profession of research scientist had come into being, and I became a professional scientific researcher myself. Hardly aware of my good fortune, I worked for half of my career through what proved to be a golden age of scientific research: the quarter century that followed that war.

Techniques, knowledge and even the social and professional environment in which scientists work have all changed again since those heady days, but the underlying spirit, the day-today frustrations and the occasional excitement of discovery persist. My story centres on a branch of biology called microbiology. This is the study of tiny creatures the majority of which cannot be seen without the aid of a microscope, but which have a quite disproportionate effect on our environment and daily lives. Most people know them as germs, the organisms that make one ill, but in fact relatively few types cause disease; the majority are beneficial, or at least neutral. It would not be appropriate to enlarge upon all that just now; certain microbes will appear in my story in due time. Microbiology as a distinct discipline within biology scarcely existed until the mid-twentieth century, but since then it has mushroomed. In illustration, in 1945 exactly 241 biologists who were especially interested in microbes came together and formed Britains Society for General Microbiology, a learned society dedicated to the study of these beasties. By 1970 that societys membership had grown to 2900 and in the mid 1990s it passed 5000. That increase in membership, over 20-fold, reflects an explosive growth in research on and interest in the subject, which took place throughout the developed world during that period. I contributed my mite to that growth. But this is not an account of the development of the science, nor is it a proper autobiography. It is a subjective account of what it was like to play a small part in that intellectual adventure, especially of the people I met and the things I did. I have leavened it with an account of the tinier part I played in a musical revolution, which was fortuitously happening alongside.

Why, you may well ask, should you, the reader, have the slightest interest in a subjective account of a period of intellectual development which is already history, with outlooks and techniques that have already been transformed enormously by changes in social organisation, by the internet, and by the vagaries of popular taste and understanding? Well, there is a good reason. Scientific research shares with jazz a subjective exploratory quality (its practitioners are always seeking), and both blossomed spectacularly during the later 20th century. Yet like jazz, science became belittled and distorted by market forces as the twenty-first century arrived, so there are lessons to be learned. But I shall only hint at them, for this is not a nostalgic polemic, nor a call to reverse history. It is simply a personal account of a period of intellectual and cultural innovation which may yet prove to have been exceptional.

And it is not, I repeat, an autobiography (even if it is autobiographical in approach). But since I necessarily appear often in my story, it is only proper that I introduce myself briefly.

I was born in London, England, within the sound of Bow Bells, on June 24, 1922. My only sibling, my brother Oliver (1), was born a couple of years later. Oliver became famous, with artist Peter Firmin, for writing, making and presenting television films for children. They were very good. Often, in later life, people would say to me, Are you the Postgate? I just loved The Clangers . Or perhaps it would be Ivor The Engine , Noggin The Nog , Bagpuss or another of Oliver and Peters sensitive productions that they loved. But I, by then quite a large frog in my own frog-pond of microbiology, was not envious; I was happy for him. My father was Raymond Postgate (2), classicist, historian, novelist, gourmet, socialist writer and propagandist, broadcaster and journalist; he was a widely known polymath of the mid twentieth century. Somewhat to his dismay he became most famous in the fourth of these contexts: he founded and edited for many years The Good Food Guide, an annual compendium of British restaurants based on customers recommendations. In consequence I had also to accustom myself to being asked to advise on good places to eat, and I was once elected to a wine committee because I bore my fathers surname.

Next page