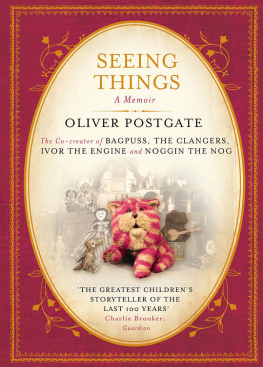

There is a period from early middle-age onwards when one is prone to become nostalgic about the childhood brand of sweets one ate in the playground and the kind of toys one played with in the bedroom: ooh, those Spangles, foaming shrimps and rice paper flying saucers aah, good old Mousetrap, Etch-a-Sketch and Slinky. We remember too the intensity of concentration and ecstasy with which we watched television during what my generation is convinced was the Golden Age of childrens broadcasting: Rentaghost, Robinson Crusoe, Blue Peter and above all, supremely above all the masterpieces of Oliver Postgate, Pogles Wood, Noggin the Nog, The Clangers, Bagpuss and Ivor theEngine.

From todays perspective, when the smallest amount of success is recognised with instant celebrity and riches, it seems extra ordinary that Postgate and his partner at Smallfilms, Peter Firmin, could have penetrated, stimulated and entranced the minds and imaginations of so many generations of children and yet themselves have remained relatively anonymous. From what I know of Oliver Postgate, riches and celebrity were never his goal.

The story of how he and Firmin started Smallfilms and began their thirty year journey as storytellers is well told by Oliver in this wonderful autobiography. Few of his early contemporaries might have guessed that Oliver would become a childrens writer, puppeteer, artist and narrator and even fewer would have guessed that his career would provide such a contribution to the richness, comity and joy of Britain. He was either too modest or too unaware of the reach and importance of his programmes ever to vaunt his achievements, but they were inestimable.

The levels of charm, narrative pleasure, characterisation, wit and complete lack of condescension apparent in all of Postgates work were rare enough then; today they are all but extinct. During bouts of childhood theism, I always supposed that if God had a voice it would be that of Oliver Postgate, the same matchless blend of authority, kindliness and humour. And if Oliver was God then we were all inhabitants of the planet far, far away where the Clangers live, where we could also find the Soup Dragon, Noggin, Olaf the Lofty, Ivor, Professor Yaffle and Jones the Steam, not to mention that old, saggy cloth cat, baggy, and a bit loose at the seams who starred in what was voted the best childrens programme of all time in a 1999 poll.

There are all kinds of ways of thinking about service: there is the kind Oliver never had truck with, military service, but, as he proved throughout his long, fulfilled life, it is possible to serve your country by inspiring its children and enriching its culture. There may be no medals struck for that, but there is the award of the abiding love and gratitude of millions.

DISCLAIMER

This is not a story, this is a life.

Having spent much of my life writing stories, I am used to being in control of the material I have thought up. I can alter it, mould it to my fancy and fit it tidily into a plot with a beginning, a proper middle and an end.

I tried to do the same with this and of course it didnt work. My life was already there, already fully inconsistent, irrevocably tangled, ill-timed and beset with incongruous events.

I suppose if I had been a dedicated person, one like my grandfather, who had a single guiding purpose throughout his life, there might have been a significant narrative on which to thread the events. But, although I have committed myself fairly passionately to various causes and purposes, these have come and gone as randomly as the circumstances that gave rise to them.

Even the main work of my life, making films for childrens television Noggin the Nog, Ivor the Engine, The Clangers, Bagpuss and the others was not something I deliberately trained for and set out to do. It was something I slipped into almost by accident, because of some trouble with magnets.

So, in the end, I simply looked through my memory for the pieces that have, for reasons of their own, stayed with me, perhaps because they once made sense, illuminated some perception, caused grief or joy, or were just fun. I have assembled the incidents in more or less chronological order and have put together what seems to be a sort of travel book.

The engine wasnt reliable, the track was badly laid, it led through dark tunnels and into weedy sidings, and as to where it was heading your guess is as good as mine!

But I hope you will enjoy the scenery.

Oliver Postgate

December1999

I. Going back.

On a dull day in the early 1990s, I took the number 13 bus to Hendon, got off at the corner of Shirehall Lane and walked along it towards the house where I was born.

Shirehall Lane, a quiet suburban street, was definitely familiar. The big elm trees had gone but the same houses were there, though they seemed smaller and closer together than I remembered. But as well as that, something was different, something was missing. Then I saw what it was: people. Nobody was coming or going, nothing was happening. The street was deserted.

As I walked I tried to conjure up the people who used to be about. For a start there were two sorts of ice-cream man, Walls and Eldorado. They would be coming along on their box-tricycles, pinging their bells. Errand boys on their heavy bikes would whistle as they passed. The dustmans cart had two big horses. The ragand-bone man had one very small horse which pulled a small cart loaded with strange articles. The ice-man had a noisy black lorry which dripped. He carried a huge gleaming block of ice on a sacking pad on his shoulder, holding it with a pair of fearsome black tongs I was afraid of him. Hopeful people with suitcases were going from door to door selling things brushes, laces, insurance, salvation to the housewives in the houses.

I turned the corner into the cul-de-sac and saw a line of small, shabby, semi-detached houses. In 1925, in one of these, number four, I was born and had spent the first ten years of my life. I walked up to number four and stood in front of it. No wave of recognition came over me, no golden memories flooded back into my heart. The only feeling I had about that poky pebble-dashed house was that it was quite extraordinarily small.

Then, gradually, I began to realize what was wrong. In those days I had been much nearer the ground. So, rather creakily, I lowered myself on to all fours, leaned forwards, nudged open the garden gate with my head and peered in at child, or perhaps large dog, level.

That did the trick. The first thing I saw, just inside the gate, was a piece of thick metal pipe sticking up out of the ground. On top of it was a small metal box with a curved top and a grille in its side. I dont know what it was a drain-ventilator perhaps but sixty-five years before I had known it well and had enjoyed its company. I now looked at it with great affection, recalling very clearly the feel of its sun-warmed metal under my hand.

Beyond the pipe-thing, under the skinny privet hedge, I could feel again the black beetly earth between the roots and, behind that, at the foot of the house, I saw with a shudder the violent texture of the edge of the rendering. There the bottom of the thick stony skin of the house had curled up and broken off, leaving a jagged edge of powdery cement to moulder away and suppurate shiny brown pebbles. The mixture had fallen as a loose gritty scree against the side of the house. It was still there.

Feeling slightly foolish, I hauled myself to my feet and dusted off my knees. So, yes, that was the house. I now recognized the raised brick path which wended its way from the gate to the front doorstep. But it was only three paces from end to end, and where was the wide lawn where the tall horn-poppies grew? I had roamed the flower-beds lifting off their pointed hats so that the bright yellow-gold flowers could spread out in the sun, and when a bee landed on a flower I would stroke its back with my finger.