Copyright Notice

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 2.0

eISBN 978-0-9575193-1-2

Published by DirectAuthors.com Ltd.

Verry House,

10a Chine Crescent Road, Bournemouth

BH2 5LQ.

www.directauthors.com

DirectAuthors.com Ltd.

Registration Number 08322704

Copyright Joe Simpson 1993

The right of Joe Simpson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

First published in the UK by Vintage, 1994.

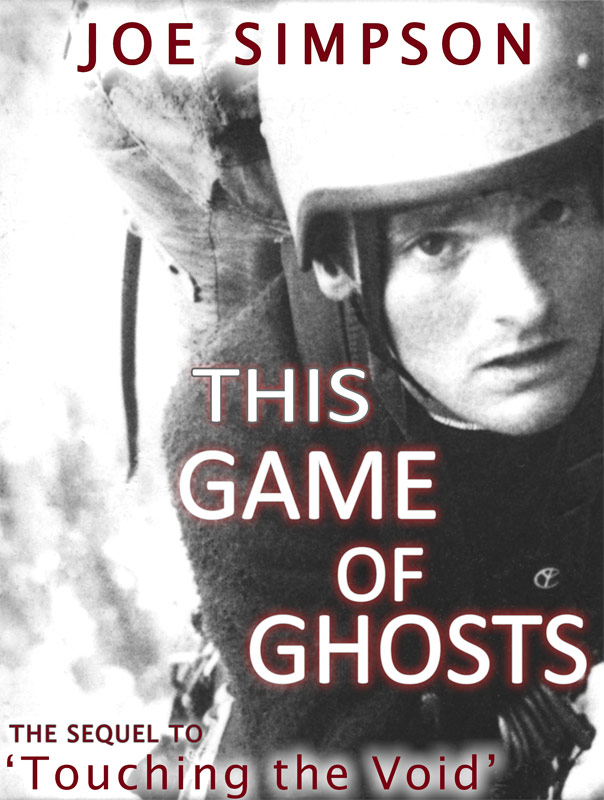

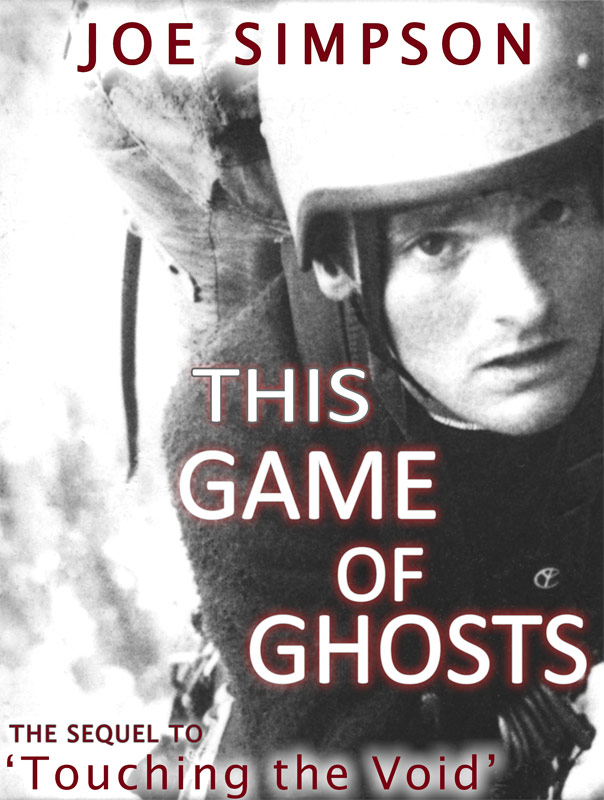

This Game of Ghosts

By

Joe Simpson

To my God-Daughter

Rosie Catherine Geraldine Hayman

Ill go with you, then,

Since you must play this game of ghosts. At listening-posts

Well peer across dim craters: joke with jaded men

Whose names weve long forgotten.

Sigfried Sassoon, To One Who Was with Me in the War

INTRODUCTION

FEAR IS THE KEY

A spasm of pain e rupted in my broken leg as it caught across the mules flank. Simon and Richard gave another powerful shove and I was up in the high pommelled saddle, grabbing desperately at the mules mane to stop myself toppling over the other side. I felt hands pushing my left foot into the leather box of a stirrup and pressed down hard to get myself upright in the saddle. I swayed unsteadily for a moment and waited with my eyes tight closed for the flushes of pain to subside.

Are you okay? Simon asked. I opened my eyes and peered down at his anxious face.

Yes. Its going away now. I glanced across at Richard, who grinned encouragingly. Simon, I dont think I can cope with this.

You have to. We cant risk infection.

My right leg was protruding stiffly from the cushion of Karrimats draped across the saddle. I remembered what it had looked like when Simon had cut away my trousers. Bloated into a thick log of fatty swelling with purple streaks betraying the haemorrhaging where the knee and ankle had been shattered, it had felt strangely separate from me. I had been dragging it around in that state for so long that it seemed more like a piece of unwanted offensive baggage than part of my body.

The mule driver, Spinosa, took the reins and, clicking his tongue, urged the animal into a slow walk. I almost fell.

Simon... I pleaded, but he ignored me and slapped the mule on its flank.

Richard, I cant...

Its all right, Joe, well be on each side. Well take it easy. Youll be okay.

We jolted off down the high Andean valley, leaving the deserted campsite and the lifeless Sarapoqoucha lake behind us. I glanced back as the mule stepped delicately across the icy stream running down the centre of the scree-strewn valley. Yerupaja soared majestically into the sky, Siula Grande lay somewhere behind it. A few cotton wool clouds clung to the summit ridge. In the foreground I saw the dam of compacted moraines down which I had crawled in the snow-swept night. The snow had melted in the morning sun. There was no trace of the slithering tracks I had made. It seemed so long ago now, so hard to believe it had ever happened.

Simon walked ahead of the mule. He turned for a last sight of the mountains we were leaving and caught my glance. For a moment there was an empty lost gaze in his blue eyes before he smiled gently, as if to say dont worry, its over now, its time to leave , and then he walked on without looking back again.

For hours the jarring, painful riding continued. I slipped between semi-consciousness and screaming wakefulness as the mule crashed my injured leg into trees, bushes, boulders and walls, despite the best efforts of Spinosa.

I couldnt understand why Simon was in such a hurry but I was too weak to argue. If I had seen myself, I would have known that it had nothing to do with a fear of infection. The sunken eyes and emaciated face would have been enough to tell me that my leg was the least of his worries. In four days of crawling alone down the mountain, dragging my unwanted limb behind me, I had lost over three stones in weight, almost 40 per cent of my usual body weight. Despite the sweet tea and porridge forced down my throat I was dangerously weak, enfeebled almost to the point of collapse, and Simon knew it. He had smelt the acetone on my breath, a side-effect of serious starvation. No amount of tea and porridge would help me. I needed glucose drips, tender loving care, hospital treatment, anything but being stuck in a remote high camp. By comparison the state of my leg was insignificant. If it had been an open fracture, the stink of gangrene would already have poisoned the air. Fortunately it appeared only swollen and battered and sore, but not life threatening.

I watched it loll heavily in rhythm with the mules stride and once again my eyes began to close. I was so tired, so deathly tired. I tried to think about everything that had happened, tried to make myself believe that it was all over, but it was useless. I couldnt lose the memory of Simons eyes when he had seen me high on the north ridge with a broken leg and the sad pitiful look he had been unable to hide. The certainty that I was going to die had been so strong at that moment. I knew I could never forget those eyes, that odd air of detachment, the unnerving pity in the stare, as if from a witness to an execution.

I remembered the panic surging through me, a belief that he would leave me and that I would die alone. And then after the endless agony of being lowered on the rope in freezing cold that sucked the last of the fight from me the fall. When he had cut the rope it had been almost a relief a silent swooping, weightless, fearless fall into darkness, only to find it wasnt all over. So much worse was to follow, more than I could ever have imagined.

As the mule stumbled I jerked awake and looked wildly around me, seeking Simon. He was there ahead of us, walking steadily, head down. He was there. It was so important that he was there. He was company and friendship, proof that I was alive, confirmation that the loneliness had been banished.

I kept glancing at Simon, at Richard and Spinosa, even at the mule, still bewildered by the sudden reunion with living things. So long alone and then so many people, so much more to do. It confused me. I could scarcely grasp how desperate I had been.

During the long hours of darkness and gloom in the crevasse I had been so convinced of a slow death that I had preferred a form of suicide to the untold days of madness while waiting to die of a broken leg. I could scarcely grasp how desperate I had been. Only twice had the true enormity of what it meant seeped into my mind. The first had been on the ice ledge deep in the crevasse, when suddenly I knew that either Simon had died or left me to die, and that there was no way out of the crevasse. That had been a time of hysteria, with one lucid moment in which I had made the hardest and the most frightening choice of my life. I doubted whether I would ever be faced with such a choice again.

Next page