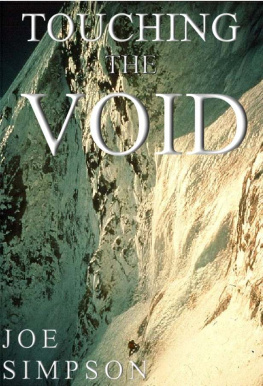

TOUCHING THE VOID

Joe Simpson

In presenting Joe Simpson with the 1988 Boardman Tasker Award, Janet Adam Smith said that Touching the Void was a story far beyond what any respectable fiction writer would dare to invent. Its all true but the telling has all the force of imaginative fiction, with a gathering momentum and suspense that makes one read on and on, even though one knows the story must have a good ending because Simpson has lived to write it.

Magnus Magnusson, presenting it with the 1989 NCR Award, said: It is not just a book about mountaineering. Ultimately it is about the spirit of man and the lifeforce that drives us all.

BY JOE SIMPSON

Touching the Void

The Water People

This Game of Ghosts

Storms of Silence

Dark Shadows Falling

VINTAGE

Published by Vintage 1997

10 9 Copyright Joe Simpson 1988

The right of Joe Simpson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, 1988

Vintage

The Random House Group Limited 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London SW1V 2SA Random House Australia (Pty) Limited

20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney,

New South Wales 2061, Australia

Random House New Zealand Limited 18 Poland Road, Glenfield, Auckland 10, New Zealand Random House (Pty) Limited Endulini, 5a Jubilee Road, Parktown 2193, South Africa The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009 www.randomhouse.co.uk A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 09 977101 2

Papers used by Random House are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

Joe Simpson

TOUCHING THE VOID

With a Foreword by Chris Bonington

To

SIMON YATES

for a debt I can never repay

And to those friends who have gone to the mountains and have not returned CONTENTS

Foreword by Chris Bonington

Beneath the Mountain Lakes

Tempting Fate

Storm at the Summit

On the Edge

Disaster

The Final Choice

Shadows in the Ice

Silent Witness

In the Far Distance

Mind Games

A Land Without Pity

Time Running Out

Tears in the Night

Postscript

Epilogue: Ten years on ...

Acknowledgments

FOREWORD

by Chris Bonington

I first met Joe in Chamonix last winter. Like many climbers he had decided it was time to learn to ski, had no intention of taking formal lessons and was teaching himself. I had heard and read stories about him, of desperately narrow escapes on the mountains, particularly his latest escapade in Peru, but they had made only a limited impact.

Sitting beside him in a bar in Chamonix it was difficult putting the stories and reputation to the person. He was dark, with a slightly punk hairstyle, and there was something abrasive in his manner. I found it difficult to take him in my mind from the streets of Sheffield into the mountains.

And I didnt think much more about him until I read the manuscript of Touching the Void. It wasnt just the remarkable nature of the story and it was remarkable, one of the most incredible stories of survival that I have ever read - it was the quality of the writing that was both sensitive and dramatic, capturing the extremes of fear, suffering and emotion both of himself and his partner, Simon Yates. From the moment Joe slipped and fell, breaking his leg on the descent, through his solitary agony in the crevasse until the moment he crawled into their base camp, I was riveted, unable to put the book down.

To put Joes struggle for survival in perspective, I can compare it to my own experience on the Ogre in 1977, when Doug Scott slipped whilst abseiling from the summit and broke both legs. At this stage the situation was similar to the early part of Joes ordeal. There were just two of us near the top of a particularly inhospitable mountain. But for us there were two other team members in a snow cave on the col just below the summit block. We were caught by a storm and took six days, five of them without food, to get down. On the way I slipped and broke my ribs. It was the worst experience I have ever had in the mountains and yet, compared to what Joe Simpson went through on his own, it begins to pale.

A close parallel happened on Haramosh in the Karakoram in 1957. It was an Oxford University party trying to make the first ascent of this 24,270 foot peak. They had just decided to turn back; two of the members, Bernard Jillot and John Emery, wanted to go just a little farther on the ridge to get photographs and were swept away in a wind slab avalanche. They survived the fall and their team mates went down to rescue them, but this was only the start of a long-drawn-out catastrophe, from which only two emerged alive.

Theirs, too, was an intriguing and very moving story but it was told by a professional writer and, because of this, lacks the immediacy and strength of someone writing at first hand. This is where Joe Simpson scores. Not only is it one of the most incredible survival stories of which I have heard, it is superbly and poignantly told and deserves to become a classic in this genre.

February 1988

All men dream: but not equally.

Those who dream by night in the dusty

recesses of their minds wake in the day

to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers

of the day are dangerous men, for they may

act their dreams with open eyes, to make it

possible.

T.E. Lawrence, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom

I

BENEATH THE MOUNTAIN LAKES

I was lying in my sleeping bag, staring at the light filtering through the red and green fabric of the dome tent. Simon was snoring loudly, occasionally twitching in his dream world. We could have been anywhere. There is a peculiar anonymity about being in tents. Once the zip is closed and the outside world barred from sight, all sense of location disappears. Scotland, the French Alps, the Karakoram, it was always the same. The sounds of rustling, of fabric flapping in the wind, or of rainfall, the feel of hard lumps under the ground sheet, the smell of rancid socks and sweat - these are universals, as comforting as the warmth of the down sleeping bag.

Outside, in a lightening sky, the peaks would be catching the first of the morning sun, with perhaps even a condor cresting the thermals above the tent. That wasnt too fanciful either since I had seen one circling the camp the previous afternoon. We were in the middle of the Cordillera Huayhuash, in the Peruvian Andes, separated from the nearest village by twenty-eight miles of rough walking, and surrounded by the most spectacular ring of ice mountains I had ever seen, and the only indication of this from within our tent was the regular roaring of avalanches falling off Cerro Sarapo.

I felt a homely affection for the warm security of the tent, and reluctantly wormed out of my bag to face the prospect of lighting the stove. It had snowed a little during the night, and the grass crunched frostily under my feet as I padded over to the cooking rock. There was no sign of Richard stirring as I passed his tiny one-man tent, half collapsed and whitened with hoar frost.

Squatting under the lee of the huge overhanging boulder that had become our kitchen, I relished this moment when I could be entirely alone. I fiddled with the petrol stove which was mulishly objecting to both the temperature and the rusty petrol with which I had filled it. I resorted to brutal coercion when coaxing failed and sat it atop a propane gas stove going full blast. It burst into vigorous life, spluttering out two-foot-high flames in petulant revolt against the dirty petrol.

Next page

![Simon Brett [Simon Brett] - Mrs. Pargeter’s Point of Honour](/uploads/posts/book/142155/thumbs/simon-brett-simon-brett-mrs-pargeter-s-point.jpg)

![Simon Brett [Simon Brett] - A Nice Class of Corpse](/uploads/posts/book/142089/thumbs/simon-brett-simon-brett-a-nice-class-of-corpse.jpg)