Foreword

Mark Westman

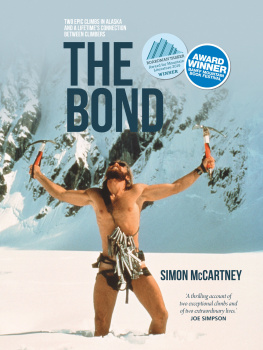

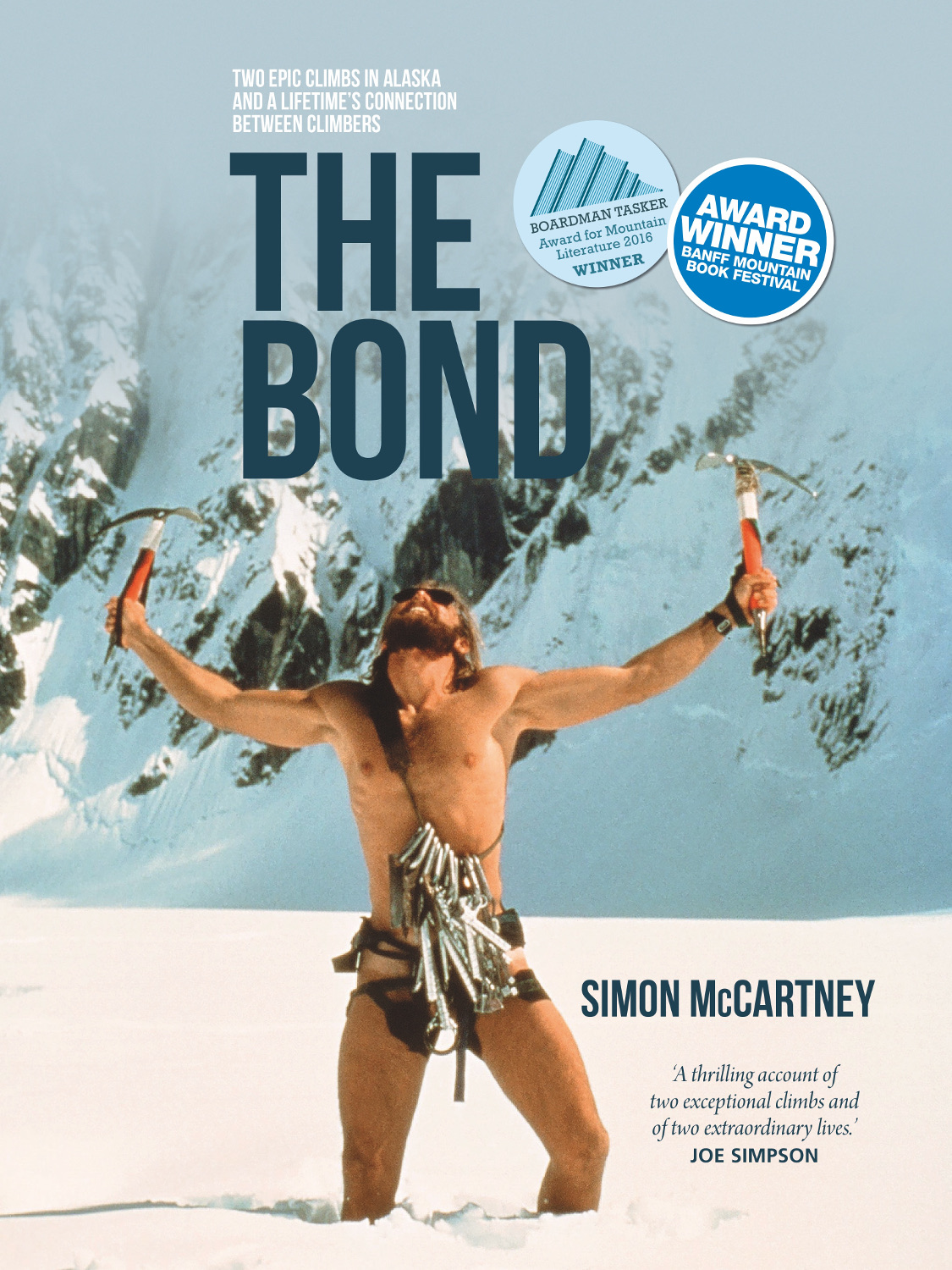

In 1977, Jack Roberts, a California Stonemaster and experienced young alpinist, teamed up with Simon McCartney, a highly motivated twenty-two-year-old Brit who had cut his teeth climbing in Europe with some of the most respected mountaineers of the time. Over the next three years the pair enjoyed a magical partnership during which they completed two of the boldest and most audacious climbs in the history of Alaskan alpinism.

The north face of Mount Huntington is one of the most dangerous walls in the Alaska Range, and Denalis south-west face is one of the largest and most technically difficult. Roberts and McCartney made the first ascents of both, pushing the boundaries of boldness, risk, commitment and difficulty, utilising a style and attitude that was on the cutting edge for its time. Eschewing any notion of fixed ropes or siege tactics, and with success as their only option, they walked to the foot of these faces with the bare minimum of gear and simply started climbing.

The tale of these two legendary climbs, and of the Too Loose expedition (as the duo came to refer to themselves), was only ever documented enough to arouse curiosity, leaving decades of mystery surrounding the ascents of these savage mountain faces and an absence of appreciation for one of the strongest climbing partnerships of its time. I was one of those captivated by these enigmatic ascents, intrigued by the cryptic accounts that accompanied them, and inspired by the climbers vision.

In the mid 1990s, as I made my first of many visits to Alaska, I endeavoured to consume every piece of local mountaineering literature and history I could find. At this time, most information was largely found in the American Alpine Journal and in Jonathan Watermans book High Alaska, the latter of which became my personal holy scripture. As a novice alpinist with grand ambitions, I found that the colourful history of Alaskan ascents fired my imagination as much as the mountains themselves. The big faces and ridges of the range held heart-stopping tales of bravery, boldness, commitment and vision.

Pervading these stories almost universally was a spirit of teamwork and camaraderie that is seldom witnessed in ordinary pursuits. I wanted to be like the people in these stories to meet the challenges of these beautiful mountains in the company of my closest friends, to learn, to progress, and to create my own unique experiences. I admired climbers who let their actions and skills speak for them, those who used alpinism as a vehicle for personal challenge and self-discovery rather than for a vacant pursuit of fame or attention.

I wanted to be like Jack and Simon.

Mount Huntington was one of my earliest mountain obsessions. It looks like a mountain should look: steep, forbidding and with a perfect symmetry of razor-sharp ridges rising to a pointed summit. There is no easy way up the mountain and the difficulties are varied and continuous. In 1995, en route to Denalis south buttress, I skied directly beneath Huntingtons perilous, 5,500-foot-tall north face. It would be hard to imagine a more dangerous wall. A steep and difficult rock band guards the base, and above that the face is stacked with multi-tiered hanging glaciers and sracs. The complete length of the summit ridge is a continuous mass of large cornices, and the face is generally angled such that any snowfall will trigger an immediate barrage of spindrift avalanches. There is no line which could be considered remotely safe to climb, and camping in the valley of the Ruth Glaciers west fork, beneath the face, provides an intimidating and humbling experience as avalanches roar from the wall on a regular basis, with colossal blast clouds sweeping the entire width of the valley. It was hard for my inexperienced mind to imagine that the face had been climbed when I was eight years old.

But I knew there were two climbers who had ignored conventional wisdom and believed, however naively, that their skills and the strength of their partnership were powerful enough that they could create their own luck. Jack Roberts and Simon McCartney were not only very skilled climbers, they were also bold and brash, and any ascent of Huntingtons north face required such an attitude, if not outright arrogance, to believe one could survive it.

Roberts submitted a report to the 1979 American Alpine Journal which was an entertaining read, written as a stream of consciousness, a metaphorical style which wryly and eloquently alluded to how serious and dangerous the ascent had been. More specifically, his report focused less on the details of the climb and more on the situations, his connection with Simon, and dreamy ruminations on what drives him to seek such experiences. The article was in fact a brilliant essay on difficult alpine climbing which made a strong impression upon my youthful and ambitious mind.

One line succinctly captured the essence of the ascent:

We were definitely bluffing our way up this mountain without a clue where we were going. The only thing that was certain was that the correct way off was up. Uninterested in anything except survival, Simon and I fled from one sheltered spot to another.

There is often a raw simplicity that characterises hardcore alpinism, which is also one of its greatest attractions. I would allow these words to guide me into and through many intense situations of my own in the future.

Roberts continued:

On again and, moving higher, I was puzzled, a trifle alarmed. The belay stance was supposed to be here; it must have moved! Deciding not to sound panic-stricken, I yelled down to Simon. No belay here. Move the belay up fifteen feet more. Simon didnt understand. Here I come. Got me on? For a while we climbed roped together without belays.

Simply being on a glacier was serious to me at the time I read this passage and I was in complete awe of people who climbed technical ground in the mountains. This sort of boldness, described in casual, humorous and low-key terms, left me dumbstruck. It revealed attitudes and options which up until then I had not considered possible.

Roberts reflected further during one of Simons leads:

Climbers who choose to pioneer first ascents up difficult and dangerous faces on high mountains have chosen to be crazy people such as Simon and I. For my part I have chosen to be crazy in order to cope with a crazy world and have adopted craziness as a lifestyle. Only on becoming convinced that the world I left behind in Los Angeles is sane, could I give up my craziness. And that cannot be done. A climber entering the subculture of a climbing community accepts his alienation from larger society and proclaims he is a full-fledged normal person that it is others who are abnormal. Simon meanwhile is gripped speechless above me, unaware that his faithful belayer is spacing out on crystals of ice and snow. There is some comfort to know that I am tied into somebody who is also crazy.

The words resonated in my consciousness as I read them. I, too, was raised in southern California; I was twenty-five years old, three years out of school and freshly laid off from an office job that was deeply dissatisfying compared to the life of mountain adventure I dreamed of and which consumed every one of my weekends. I was at the headwaters of the life I truly wanted to lead and Jacks words strengthened my resolve to take the proper path. I was also in the early stages of one of my greatest alpine partnerships, that with my friend Joe Puryear, and aspiring to the biggest routes. In our long apprenticeship, one of our frequent comical refrains while climbing was to quote the no belay here exchange between Simon and Jack. We didnt have the precocious skills of those two, but we jokingly adopted their attitude to break the tension of the stressful situations in which we frequently found ourselves. And happily, we each thought the other was crazy.