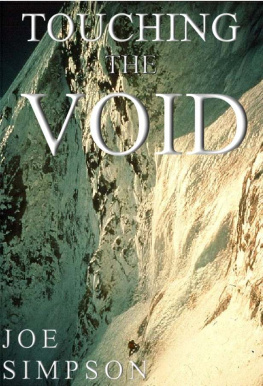

Touching the Void

Copyright Notice

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 2.0

eISBN 978-0-9575193-0-5

Published by DirectAuthors.com Ltd.

Verry House,

10a Chine Crescent Road, Bournemouth

BH2 5LQ.

www.directauthors.com

DirectAuthors.com Ltd.

Registration Number 08322704

Copyright Joe Simpson 1988

The right of Joe Simpson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

First published in Great Britain in 1988 by Jonathan Cape, Vintage.

About Joe Simpson

Former mountaineer Joe Simpson wrote his first book, Touching the Void, after returning from a harrowing near-death experience in the Peruvian Andes. It was subsequently made into a BAFTA Award Winning motion picture. Simpson has since written a number of best-selling non-fiction works and two novels on the subject of mountaineering. Now an inspirational speaker, he divides his time between his home-town of Sheffield and Kerry in Ireland.

Also by Joe Simpson:

The Water People (A Novel)

This Game of Ghosts

Storms of Silence

Dark Shadows Falling

The Beckoning Silence

The Sound of Gravity (A Novel)

Dedication

To Simon Yates, for a debt I can never repay.

And to those friends who have gone to the mountains and have not returned.

TOUCHING THE VOID

The th Anniversary Edition

by

Joe Simpson

With a Foreword

by

Chris Bonington

Interview with the Author

It has been 25 years since the first publication of Touching the Void . In that time much has changed, including the landscape of publishing. This electronic edition celebrates the anniversary of Joes miraculous survival, with over 50 images, including never before seen photos taken during the trip itself. Follow this link to hear Joe Simpson talking about the changes and challenges faced in those 25 years (Internet connection required - only available on certain devices).

All men dream: but not equally.

Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dreams with open eyes, to make it possible. - T.E. Lawrence, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom

FORWARD

by

Chris Bonington

(Feb. 1988)

I first met Joe in Chamonix last winter. Like many climbers he had decided it was time to learn to ski, had no intention of taking formal lessons and was teaching himself. I had heard and read stories about him, of desperately narrow escapes on the mountains, particularly his latest escapade in Peru, but they had made only a limited impact.

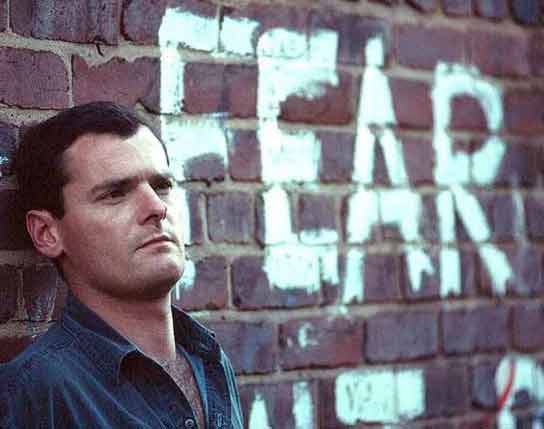

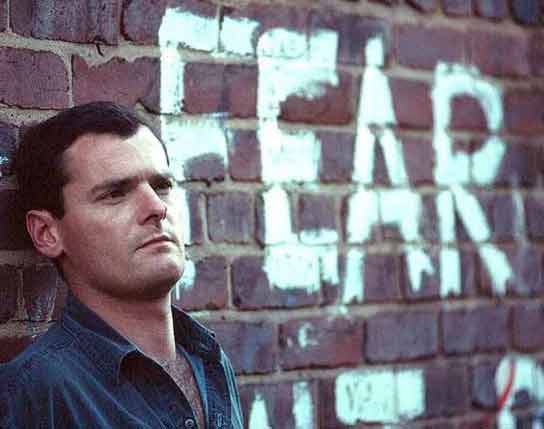

Sitting beside him in a bar in Chamonix it was difficult putting the stories and reputation to the person. He was dark, with a slightly punk hairstyle, and there was something abrasive in his manner. I found it difficult to take him in my mind from the streets of Sheffield into the mountains. And I didn't think much more about him until I read the manuscript of Touching the Void. It wasn't just the remarkable nature of the story - and it was remarkable, one of the most incredible stories of survival that I have ever read - it was the quality of the writing that was both sensitive and dramatic, capturing the extremes of fear, suffering and emotion both of himself and his partner, Simon Yates. From the moment Joe slipped and fell, breaking his leg on the descent, through his solitary agony in the crevasse until the moment he crawled into their base camp, I was riveted, unable to put the book down.

To put Joe's struggle for survival in perspective, I can compare it to my own experience on the Ogre in 1977, when Doug Scott slipped whilst abseiling from the summit and broke both legs. At this stage the situation was similar to the early part of Joe's ordeal. There were just two of us near the top of a particularly inhospitable mountain. But for us there were two other team members in a snow cave on the col just below the summit block. We were caught by a storm and took six days, five of them without food, to get down. On the way I slipped and broke my ribs. It was the worst experience I have ever had in the mountains and yet, compared to what Joe Simpson went through on his own, it begins to pale.

A close parallel happened on Haramosh in the Karakoram in 1957. It was an Oxford University party trying to make the first ascent of this 24,270 foot peak. They had just decided to turn back; two of the members, Bernard Jillot and John Emery, wanted to go just a little farther on the ridge to get photographs and were swept away in a wind slab avalanche. They survived the fall and their team mates went down to rescue them, but this was only the start of a long-drawn-out catastrophe, from which only two emerged alive.

Theirs, too, was an intriguing and very moving story but it was told by a professional writer and, because of this, lacks the immediacy and strength of someone writing at first hand. This is where Joe Simpson scores. Not only is it one of the most incredible survival stories of which I have heard, it is superbly and poignantly told and deserves to become a classic in this genre.

1 Beneath Mountain Lakes

I was lying in my sleeping bag, staring at the light filtering through the red and green fabric of the dome tent. Simon was snoring loudly, occasionally twitching in his dream world. We could have been anywhere. There is a peculiar anonymity about being in tents. Once the zip is closed and the outside world barred from sight, all sense of location disappears. Scotland, the French Alps, the Karakoram, it was always the same. The sounds of rustling, of fabric flapping in the wind, or of rainfall, the feel of hard lumps under the ground sheet, the smell of rancid socks and sweat - these are universals, as comforting as the warmth of the down sleeping bag.

Outside, in a lightening sky, the peaks would be catching the first of the morning sun, with perhaps even a condor cresting the thermals above the tent. That wasn't too fanciful either since I had seen one circling the camp the previous afternoon. We were in the middle of the Cordillera Huayhuash, in the Peruvian Andes, separated from the nearest village by twenty-eight miles of rough walking, and surrounded by the most spectacular ring of ice mountains I had ever seen, and the only indication of this from within our tent was the regular roaring of avalanches falling off Cerro Sarapo.

I felt a homely affection for the warm security of the tent, and reluctantly wormed out of my bag to face the prospect of lighting the stove. It had snowed a little during the night, and the grass crunched frostily under my feet as I padded over to the cooking rock. There was no sign of Richard stirring as I passed his tiny one-man tent, half collapsed and whitened with hoar frost.

Next page